The Marine captain unfolded his tactical map and pointed to a small gray square indicating a population center east of the Tigris River. For all the high-tech wizardry available to American commanders, he was missing something crucial — the name of the town to the north toward which the Marines’ 5th Brigade was advancing. By chance, I had just passed through the same area and could give him that information. With that, the captain ordered his handful of Bradley fighting vehicles and Humvees up the east side of the Tigris.

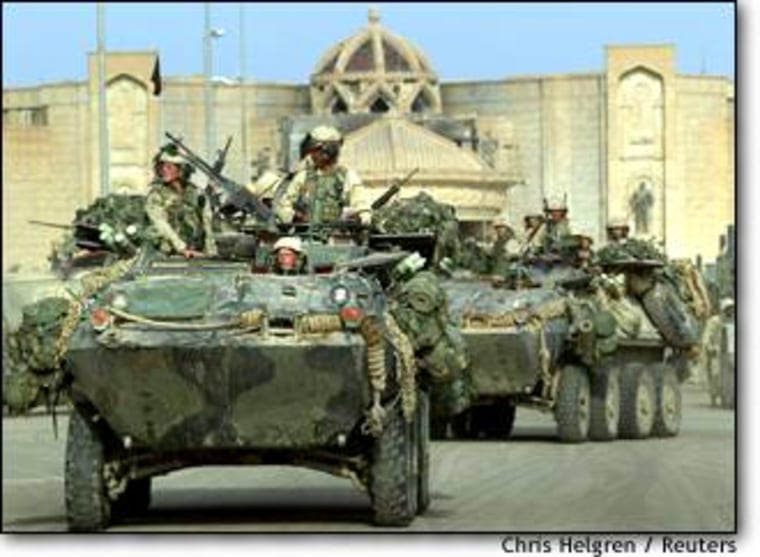

The Marines on Monday choked off Saddam Hussein’s heartland, a swathe of fertile land north of Baghdad stretching through Samarra, an ancient city on the Tigris River’s eastern shore, up to Tikrit, the Iraqi dictator’s birthplace and stronghold on the western side of the river. The U.S. grip on the north, however, was not yet firm. Battles — and chaos — could lie ahead.

Outside Tikrit Monday morning, an Arab village leader told me how Kurdish pillagers — who have been disavowed by pro-American Kurdish commanders — arrived in Arab villages in pickup trucks. Carrying cellular phones, they threatened to call in U.S. airstrikes if valuables were not handed over. Fearful — and admittedly naïve — some Arabs gave in. Now the Arab men were armed and hiding along the roadside, ready to pick off approaching cars. This was the crossfire into which the Marines 5th Brigade was heading.

When I told the Marine captain about the irregular Kurdish military forces looting Arab villages just down the road, he rolled his eyes and sighed. “Just what we need.”

STARVED FOR NEWS

The Marines I came across on Monday had largely been abandoned by their media “embeds,” who found the scene in Baghdad too exciting to push north for more battles. In candid discussions, the Marines said they were worn down by a month on the move. A few hours of napping in the hot afternoon sun in Samarra on Monday was their first down time since entering Iraq from Kuwait.

InsertArt(1864276)The sight of a reporter — and a satellite phone — roused a few from their slumber. They lined up for quick calls home. There was a lieutenant whose infant son was in the hospital, according to the last news he got weeks ago. The boy is now at home and doing well. There was sergeant major who wanted NCAA and NHL scores. And there was the captain, who gave up his turn to be split equally between three of his men. “They need this,” he said. “My call can wait.”

The Marines were starved for news. They wanted to know whether the world was seeing the “good side” of the story. “We have old ladies crying tears of joy and smothering us in kisses every day. Are people seeing that?” one lieutenant asked. Then, after an hour of chatter, they were gone, heading north to open the eastern side of the Tigris River — where all the villages I passed through on Monday still had prominent portraits of Saddam in the town squares and government buildings.

DILEMMA FOR ADVANCING FORCES

After crossing paths with the 5th Brigade, I stopped in Samarra, whose Great Mosque, once the largest in the Muslim world, remained partially standing.

On Sunday, seven U.S. Army soldiers were rescued from the city, where they had been held as prisoners of war. Marines working ahead of the 5th Brigade were tipped off to their presence by local residents. I wanted to speak to the people who turned over the American POWs, so I paid a visit to Sheik Khatan Yehiah Salim, a tribal leader in Samarra and one of the city’s few remaining dignitaries. Officials closely associated with the Baghdad regime had fled days before.

The sheik said news of the POWs had come as a surprise to Samarra’s residents, a tightly knit group where few secrets are kept for long. Khatan, a direct descendant of Islam’s caliphs, who ruled after the death of the prophet Mohammed, said he couldn’t help me find those who had helped to rescue the American POWs. But I couldn’t resist a break in his large, cool reception room — an escape from the midday heat. Khatan apologized for the lack of electricity. “It’s been this way for 10 days,” he said.

The sheik, like the skirmishes between Kurdish looters and Arab villagers, presents another dilemma for the American troops moving north. Tribal chiefs like Khatan thrived under Saddam, and were handsomely rewarded for their loyalty. Today, however, the sheik proclaims himself firmly in the American camp, and says that he “negotiated” the peaceful entrance of the U.S. forces into Samarra on Sunday afternoon. Yet 5th Brigade commanders said they had received “no fewer than three” separate letters from tribal leaders in Samarra. All of them claimed to represent the city’s population of 200,000.

Khatan said he was on friendly terms with the Americans, although he ended our lunch by saying U.S. troops should leave “as soon as possible.”

‘THE HAIRIEST BATTLE’

Earlier, when I chatted with the 5th Brigade, one platoon commander told me of a particularly harrowing battle two days earlier at Baghdad’s northern edge. I was reminded of it as I drove through the combat wasteland near the Baghdad city limits.

A platoon of Marines had been sent as forward reconnaissance to a northern Baghdad neighborhood. The residents greeted them with flowers and cheers. But just as quickly as they appeared to welcome the U.S. troops, the well-wishers vanished.

The Marines were ambushed from all directions with machine-gun fire and rocked-propelled grenades. “It was the hairiest battle so far on this deployment,” said a lieutenant from Oregon. At least four Marines were injured in the four-hour engagement.

Only when backup arrived did a clearer picture emerge. Hundreds of Saddam’s fedayeen paramilitary fighters were based in the neighborhood. Some of their support was apparently drawn from anti-U.S. militants flooding into Iraq from other Arab countries. “We picked up several Syrian passports off the bodies,” said the lieutenant.

As I arrived in the Iraqi capital, one battlefield and neighborhood was indistinguishable from the rest. The roads were littered with the charred remains of military vehicles. A smoky haze hung over the Iraqi capital, obscuring what comes next.

(MSNBC.com’s Preston Mendenhall is on assignment in Iraq.)