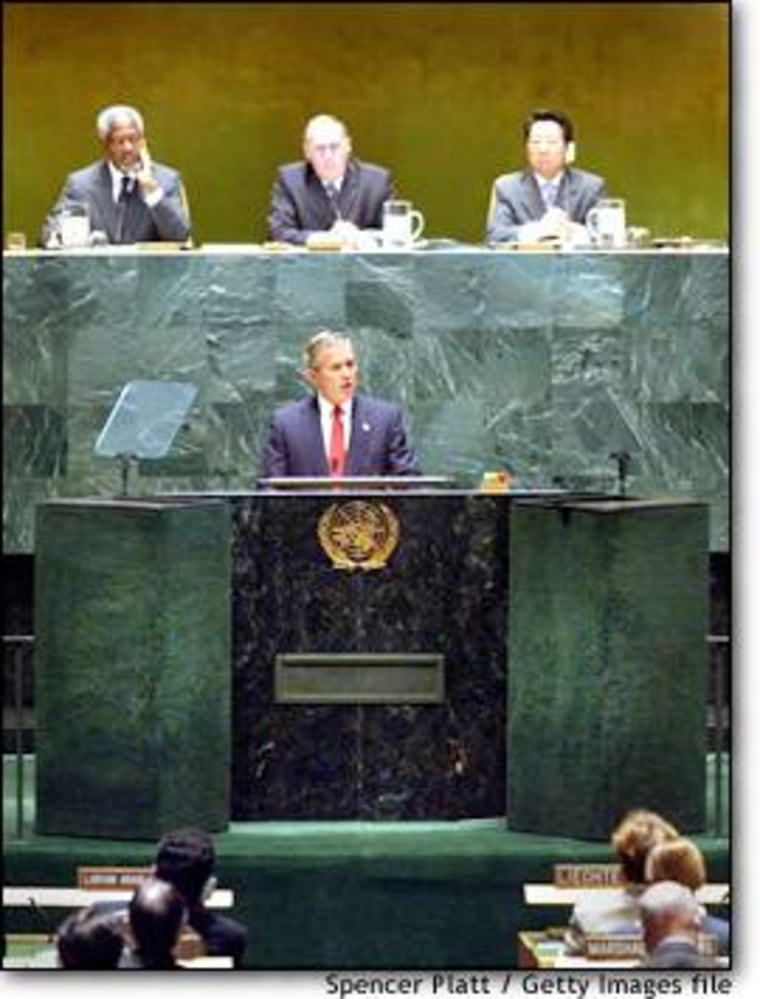

A year ago in this famous building, President Bush gave the speech of his life to the General Assembly, a speech that disarmed his critics. “Will the United Nations serve the purpose of its founding, or will it be irrelevant?” he asked. Neither the speech nor the U.N. disarmed Saddam Hussein, however. What weaponry the Iraqi dictator held ultimately fell prey to an Anglo-American invasion launched without U.N. support. Yet today, with Saddam toppled and Iraq occupied, the U.N. is anything but irrelevant, and Bush once again needs to deliver the speech of his life to set things right.

One of the most difficult twists for many Americans to follow in the tormented Iraq debate is this crowning irony: the U.N. Security Council’s refusal to rubber stamp a quick march to war against Iraq earlier this year has had the effect of strengthening, rather than weakening, the U.N.’s prestige and authority.

This is not to say that America cannot launch future pre-emptive wars against rogue states if it so chooses. America remains first among equals at the U.N. and, by virtue of its economic and military might, unrivaled in most other venues, as well.

But the messy aftermath of the Iraq war suggests that, if there is a “third act” in the terror war being scripted by Bush, it is unlikely to treat the United Nations as an afterthought.

The U.S. needs the world’s help in Iraq, and Bush know he needs to say that plainly and without rancor.

With American military intelligence now warning that even ordinary Iraqis are turning against the occupation, the need to “internationalize” the post-war force is intense and immediate. What’s a president to do?

As any good southerner will tell you, you can catch more flies with honey than vinegar. Bush will need all the honey he can pack into the General Assembly hall for Tuesday’s speech. The focus of the speech, diplomats say, needs to be practical and foreword looking: how to fix a post-war enterprise that is not going well.

“There has to be an olive branch,” says a senior Asian diplomat at the U.N. “There has to be a sense that mistakes were made, on all sides, but that the world is a better place when we find common ground. Otherwise, the speech will be counter-productive.”

Domestic political exigencies will almost certainly require Bush to tick off a list of things that have gone right. Much of Iraq is stable; a “governing council” is taking baby steps toward democracy; Saddam’s bloody reign is over. All true.

Even the embarrassing lack of evidence of the dictator’s weapons of mass destruction programs, the centerpiece of last year’s barn-burner, could be spun as good news if the president would swallow hard.

“We really thought they were there,” is all he would have to say. “We may find them still. But if I was wrong, I apologize. I was sincerely convinced.”

Cutting the deal

That done, down to business.

The U.S. currently is hoping a new Iraq resolution in the Security Council, one that would “bless” the post-war military and reconstruction effort, will grant cover to nations like India and Turkey so they might make troop contributions. The effort is stalled by two major disputes, both of them revolving around how much power the U.S. will retain:

1) When does the United States turn over control of Iraq’s domestic affairs, including important oil industry issues, to Iraqi authorities under U.N. supervision? The U.S. sees this in terms of years; others, in terms of months.

2) Should the United Nations be willing to sanction overall U.S. command of a post-war occupation? Most are willing to support this, but there will be a price.

Bush can make quick work of Point 2. Diplomats suggest that American negotiators have made significant progress in recent weeks convincing Security Council members that the U.N. is not ready to take over the entire security operation — in part, because none of them wants to send their troops to be killed. As Powell told German television Tuesday, “The U.N. isn’t ready to handle it. The U.N. has not asked for it.”

The key here, diplomats suggest, is a willingness on the part of the U.S. to report on progress to the Security Council on a regular basis. That is a point Bush should concede readily.

Ready or not?

The stickier issue is the Point 1: How much power the “Coalition Provisional Authority” of J. Paul Bremer should cede to the Iraqi Governing Council, how quickly, and with what kind of U.N. participation?

The split on this issue is more profound, with France, Russia and Germany favoring a very quick transition, possibly within six months. They argue the U.N. should play the kind of role it did in Bosnia, leading the civilian authority until elections allow Iraqis assume complete sovereignty. The U.S. argues this timetable is unrealistic, and many inside the administration suspect the French and Russian primarily want to use such a U.N. body as a Trojan Horse to get their national firms access to lucrative post-war contracts.

A U.S. diplomat, speaking on condition of anonymity, also noted that Bosnia’s own U.N. commissioner warned against rushing the transition to local authority. “Their own history argues against it,” the diplomat says.

In fact, Lord Ashdown, a Briton who stepped down last autumn, warned that “In Bosnia, we thought that democracy was the highest priority and we measured it by the number of elections we could organize. In hindsight, we should have put the establishment of rule of law first, for everything else depends on it.”

Seeking to bridge this gap, Secretary General Kofi Annan has been floating the idea of a transitional U.N. authority that would take the handoff from the U.S. but not hand full authority to the Iraqis until elections are organized. That is not politically palatable to the administration, and it risks leaving a weaker multinational force at the mercy of Sunni guerrillas, the minority group that still clings to the idea that they will control the nation when the foreigners leave.

But a deal is there to be made. Bush could propose to link the handover date to the establishment of an Iraqi police and judicial system. He could propose benchmarks for a reduction in violent attacks — from 12 a day, say, to 12 a week, with authority for various zones passing to the multinational force as, or if, violence falls away.

If, as the administration hopes, a U.N. blessing for the post-war military force encourages other nations to send troops, the “internationalization” of the force should help reduce those attacks in any case.

Why should the U.S. offer anything, you may ask? That’s a fair question. Even with its current security problems in Iraq, the U.S. could, conceivably, in several years time, pacify and relaunch a sovereign Iraq.

But even inside the administration, there is deep concern about the financial, political and human costs of going down that road alone. Putting aside electoral issues, leaving 140,000 American troops in Iraq for years could eviscerate the National Guard and leave other areas — North Korea, for instance — without a ready reserve.

Whatever Bush does, he has to avoid tearing the scabs off the arguments of last winter. Madeleine Albright, the former secretary of state, argues in Foreign Affairs this month that Bush aides who continue to portray opposition to the war as a matter of resentfulness fail to appreciate how poorly the case for war was argued.

“The American arguments simply were not fully persuasive,” writes Albright. “I personally felt the war was justified on the basis of Saddam’s decade-long refusal to comply with Security Council resolutions on WMD. But the administrations claim that Saddam posed an imminent threat was poorly supported, and was its claim of alleged connections to al-Qaida.”

Half-time is over

In short, Bush’s speech call to action at the U.N. last September was the equivalent of a great kick off: right out of the end zone, forcing opponents of the war to start on their own 20-yard-line. But the plays that followed sputtered and ultimately failed to gain traction.

Worse still, when defense stiffened and it came time to punt, the U.S. instead quit the game in a snit and took its ball home.

“Global challenges also require global solutions, and few indeed are the situations in which the United States or any other country can act completely alone,” writes Shashi Tharoor, a senior U.N. bureaucrat. “This truism is currently being confirmed in Iraq, where Washington is discovering it is better at winning wars than constructing peace.”

The good news there is that there is an organization — one American taxpayers pay dearly for — designed for precisely that job. There is nothing in the United Nations charter that limits the institution’s interventions to saving failed states. Superpowers, too, need help. Bush’s challenge is to challenge it, once again, to “serve the purpose of its founding.”