The United States is launching into a new campaign to convince the world that something must be done about a dictatorial Muslim nation on the cusp of building a nuclear weapon. The Bush administration, according to a senior administration official, is pressing the International Atomic Energy Agency to refer suspicions about Iran’s nuclear program to the U.N. Security Council. That’s the easy part. Far more difficult, officials and proliferation experts say, will be restoring the credibility of U.S. intelligence reports as a means for substantiating the kinds of allegations leveled against Iraq before the war.

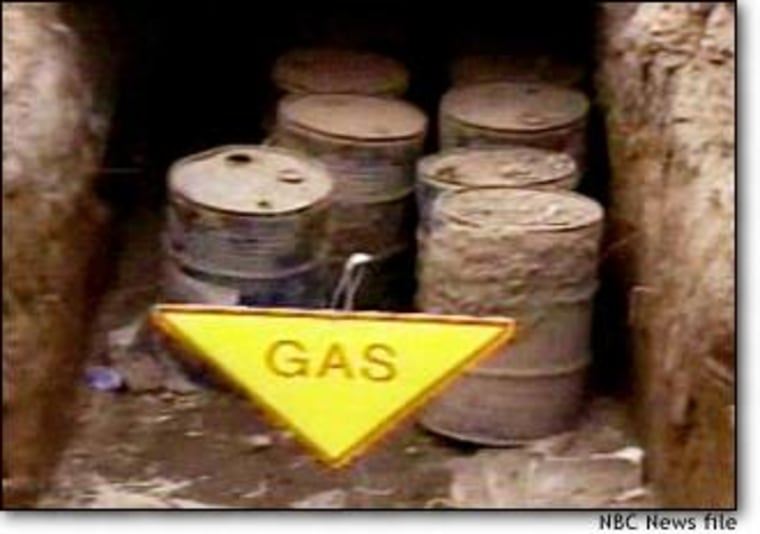

Exactly nine weeks ago, U.S. Marines helped cheering Iraqis topple a statue of Saddam Hussein in central Baghdad, a moment that briefly stifled even the harshest critics of the U.S.-led war. That same week, reports originating with Marine and Army units emerged suggesting the tip of the Iraqi chemical and biological weapons iceberg had been found: artillery shells containing blister agents, medium-range missiles tipped with nerve gas, a store of sarin and other agents at a central Iraqi weapons dump.

All of these finds, and many others afterward, were discredited after further testing. Before long, Army and Marine units stopped making such reports based on field tests, which have shown an alarming tendency to produce false positives.

Some 1,400 U.S. and British inspectors are combing the country for signs of Saddam’s WMD arsenal. Yet, in spite of the collapse of Saddam’s concealment system, the complete access to all facilities enjoyed by the inspectors and rich incentives being offered to Iraqi scientists and military officers willing to lead U.S. investigators to the “smoking gun,” no trace has been found of banned weaponry that was not already well known and catalogued by the U.N. inspection teams of the 1990s.

“I would have assumed they’ve searched major weapons depots by now, and I have to say I’m very surprised after capturing so many major officials that they haven’t turned up something,” says Dr. Gordon Oehler, the former director of the CIA’s Non-Proliferation Center.

The only thing approaching the kind of evidence the U.S. will need to prove its pre-war case is the discovery of two unusually equipped tractor-trailers. The administration believes these to be the “mobile biological warfare labs” described by Iraqi defectors and by Secretary of State Colin Powell in his final plea for support at the United Nations in February.

But even these finds are problematic. For one thing, no trace of any kind of biological agent is present on either of them. A second, more damaging point: It appears that the Bush administration, understandably eager to maximize the importance of these finds, given its lack of luck elsewhere, deliberately quashed the opinions of U.S. and British intelligence analysts who suggested that the trailers don’t really appear to be mobile WMD labs after all.

The credibility thing

Most experts believe that some form of banned weaponry will be found eventually in Iraq, though even supporters of the war concede it will take more than the odd Scud missile or empty-but-tainted artillery shell to make up for the dashed expectations.

For the Bush administration domestically, this has led to quick moves to de-emphasize WMD and play up, instead, the fact that a brutal dictator has been ousted. Indeed, in at least one sense, U.S. credibility has never been higher: When this administration makes a threat, it clearly is not just whistling “Dixie.” Nor is the U.S. military the paper tiger that many U.S. rivals optimistically portrayed in the years after Vietnam. As a war-fighting machine, it has no equal.

But the complete disconnect between what U.S. officials claimed Iraq was doing and what subsequent investigation has been able to prove is going to be a major problem for U.S. diplomacy in the next crisis.

“For this administration’s future claims to have credibility, it’s important to find the WMD in Iraq,” says David Phillips, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and an expert on postwar issues. “Otherwise, policy actions we might take to confront the regimes in Iran or North Korea won’t have credibility among our allies and the rest of the international community.”

Oehler, the CIA’s former proliferation czar, agrees. “If there isn’t anything there, then yes, that’s very damaging to what they’re going to try to do in the future in terms of pre-emptive moves,” he says. “But I still have to believe they’ll find something.”

Worst-case thinking?

Oehler, whose career at the CIA peaked under the watch of Director Robert Gates in the early 1990s, says one explanation for the overheated intelligence that led up the Iraq war could be “worst-case” thinking.

“After the first Gulf War, we started to get a lot of information suggesting that our assessment of [Saddam’s] weapons, especially nuclear, were way off, particular on quantities,” he says. “So analysts became gun-shy, began to take a ‘worst case scenario’ approach. I think that whole thing was an overreaction for CIA for not having sufficient scope on Saddam’s weapons the first time.”

This wouldn’t be the first case of intelligence overreaction. For instance, the launch of the world’s first manmade satellite in 1957, the Soviet Sputnik, panicked the CIA into grossly overinflated assessments of Soviet missile technology, soon dubbed “the missile gap,” that helped John F. Kennedy defeat Richard Nixon in the 1960 presidential election. The phenomenon recurred in 1978, when in the wake of Vietnam, the CIA and its military cousin, the Defense Intelligence Agency, started issuing alarming reports of Soviet military superiority that fueled the arms buildups of the 1980s. Only later, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, did it become clear that U.S. intelligence exaggerated Soviet power enormously, to the great benefit of defense contractors.

Blowback

But none of these intelligence gaffes led to or justified outright war. Those who opposed attacking Iraq are unlikely to let sleeping dogs lie in this case.

The British Parliament is now preparing an inquiry into the intelligence that formed the foundation of the argument for going to war against Iraq, the idea, to quote President Bush’s State of the Union message, that “Saddam Hussein has gone to elaborate lengths, spent enormous sums, taken great risks to build and keep weapons of mass destruction.” Democrats in the U.S. Congress, for reasons not hard to fathom, want to do the same, though Republicans, again, predictably, say such hearings are not warranted. Whether hearings are eventually held may depend on the Democrats’ ability, or willingness, to raise a stink about the issue. The existence of a former Senate Intelligence Committee chairman, Florida Democratic Sen. Bob Graham, in the Democratic presidential sweepstakes, makes it likely the pressure will continue.

In Britain, meanwhile, where Prime Minister Tony Blair convinced his own Labor Party to support the war by citing such intelligence, the inquiry is likely to be an ugly reckoning and a chance for Labor Party opponents of the war who felt muzzled by their leader to strike back.

The Economist, the British newsweekly, even suggested that this could mark the beginning of the end for Blair, who previously has been unassailable as a politician. As the magazine points out, “Tony Blair’s power lies in his persuasiveness. But persuasion depends on trust; and, if that goes, so does the basis of Mr. Blair’s power.”

In the longer term, even if President Bush avoids congressional hearings on the alleged politicization of intelligence, he may still find it difficult to avoid being cast as “the boy who cried wolf” the next time the United States feels the need to act pre-emptively.