When the Cold War came to a dramatic close in 1991, a new euphoria infused the U.S.-Russian relationship. In a series of summits — what journalists came to refer to as the “Boris and Bill Show” — a jocular President Boris Yeltsin and saxophone-playing Bill Clinton hammed it up for the cameras like the best of friends. But the Russian people, who saw few of the benefits of the Russo-American vaudeville act trickling down to them, didn’t buy the schtick. Today, more than a decade later, a former KGB colonel is winning the population over to the American side.

These days, just about any Russian you ask will roll their eyes, swear and sometimes spit when they hear Yeltsin’s name. The man Washington credits with burying communism also gave Russians their first post-Soviet introduction to the West.

As the “Boris and Bill” show played over and over during the eight years the two leaders shared the world stage, Yeltsin made promises of U.S.-style democracy and open markets while presiding over one of history’s biggest free-for-alls. His special formula for capitalism, buoyed by glowing words from his good friend Bill in Washington, was to allow a handful of “oligarchs” to take control of the country’s biggest industries and coat the Kremlin with dirty money.

Capital flight

Upward of $150 billion in illegal gains flowed out of Russia, stashed in foreign banks, while Russians saw few concrete signs of the much-heralded U.S.-Russian ties. One of the first — and much scorned — examples of American largesse were “noshki Busha,” or Bush legs, the surplus chicken the first President Bush sent to see Russia through the winter after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The chicken, which was supposed to be subsidized for Russian pocketbooks, ended up for sale at jacked-up prices on the black market.

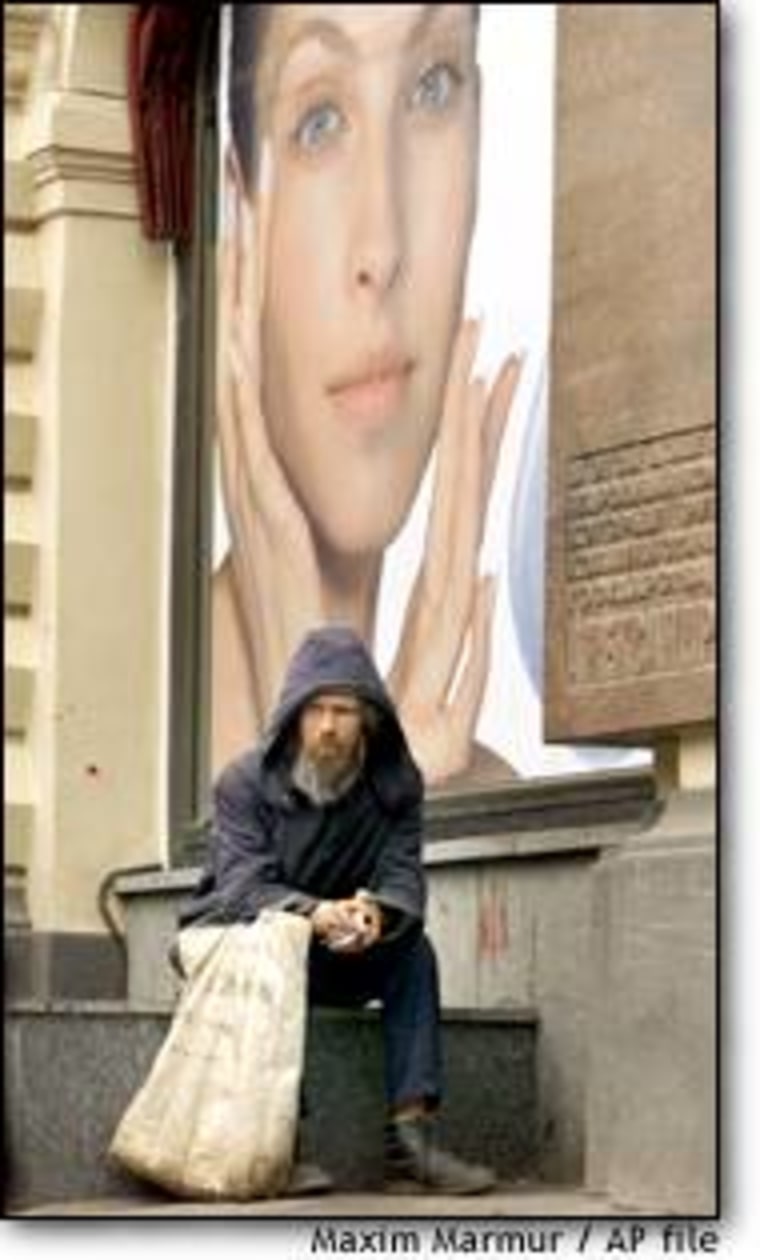

Meanwhile, average Russians saw their hard-earned rubles crash against the all-important dollar — the backbone of Russia’s emerging economy. A tide of foreign goods so scarce during Soviet times made it to Russia, but most of the products were far beyond the reach of out-of-work or underpaid teachers, engineers and doctors.

The contrast between the slap-happy “Boris and Bill Show” and the reality on the street ultimately shaped Russian public opinion. Wariness of Washington, which was seen as helping hasten — even celebrating — the Soviet Union’s demise, exists to this day.

Putin's shift

As the country’s economic straits deepened in the late 1990s, Yeltsin all but gave up on his own stalled economic reforms. During his final years in power, he sought to boost his rock-bottom popularity by invoking nationalist issues — like NATO’s eastward expansion and U.S. intervention in Yugoslavia’s wars — for personal gain.

When Yeltsin resigned unexpectedly on Dec. 31, 1999, the White House wasn’t sorry to see him go — but the Russian president’s hand-picked replacement gave the incoming Bush administration a startle. Vladimir Putin, a former KGB colonel who spent time spying on the West from former East Germany, looked set to pick up where Yeltsin left off, beating the drum of nationalism and placing reforms on the back burner.

Russia's split personality

Putin inherited a confused nation. Prodded by the “Boris and Bill Show” to embrace the policies of the West, Russians were also expected — as Yeltsin found politically convenient in his later years — to put nationalist causes before national recovery.

Putin was an unlikely candidate to reverse Russia’s course. But he did just that. After the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on the United States, Putin’s condolences and message of solidarity with Washington hit Russia’s airwaves before being played for an American audience.

The Russian leader stared down the old guard nationalists, allowing thousands of American troops to base in neighboring countries — traditionally within the Kremlin’s sphere of influence — to prosecute the U.S. war on terrorism.

Many Russians also began to feel America’s own security problems forced Washington to sympathize with the Kremlin’s war on Chechen rebels and terrorists, though the White House has been reluctant to give a clear endorsement of the scorched-earth tactics of the Russian military in breakaway Chechnya.

Lingering suspicions

And although Russians roundly condemn the Sept. 11 attacks, a poll on the tragedy’s anniversary showed that the population, a majority of which thinks the United States “got what it deserved,” does not yet fully trust American policies.

Nevertheless, Putin has kept up his message that Russia’s future lies with the West. And, most importantly, the Russian leader’s vision has come unclouded, and hinged to key economic reforms that — thanks to Russia’s oil revenues — are finally bearing fruit. The Russian economy is on the rebound after the 1998 currency crash, and the country’s stock market is one of the best performing in the world.

Few leaders can be accused of acting selflessly, and Putin is no exception. The Russian president has clearly calculated the political gain from his pro-Western policies. But this time the Kremlin and Russians have a common goal — and it’s economic.