The military occupation of Iraq is barely two weeks old and already the complexity of what the United States has embarked upon is becoming apparent. American officials cite the successful transformation of Japanese and German society after World War II as a hopeful model for what might unfold in Iraq. Yet Iraq’s particular ingredients — ethnic rivalries, religious schisms, repressed minorities, tribal customs and a deep-seated suspicion of American intentions — pose obstacles fundamentally different than those encountered by the United States following past wars.

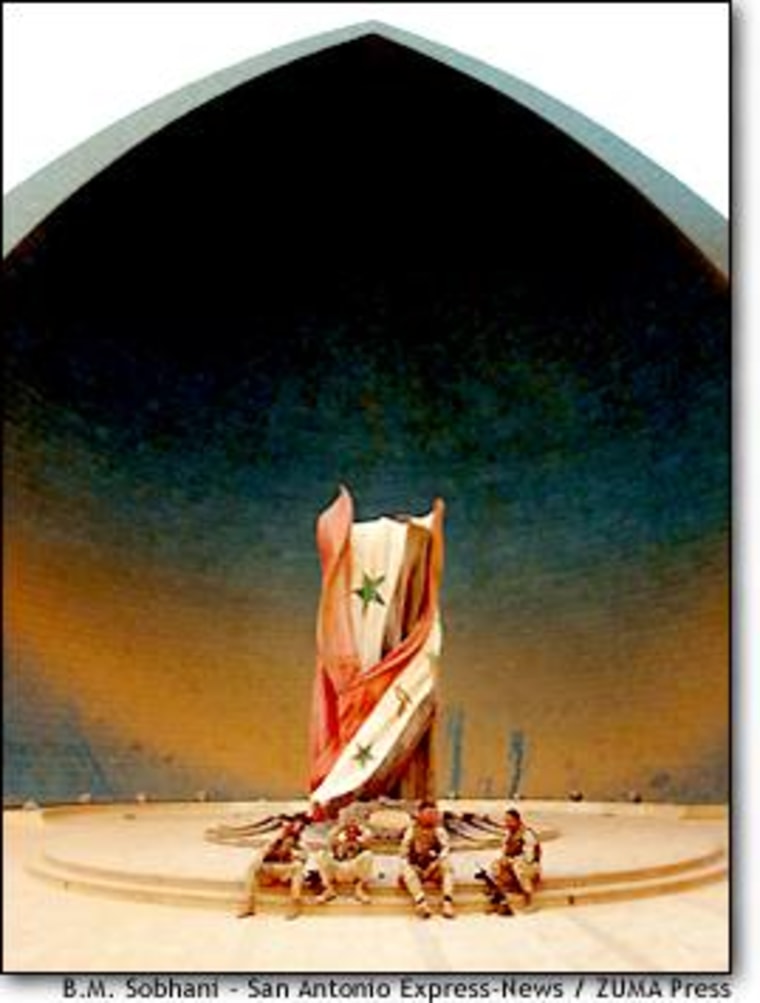

The lightening-quick American military victory over Iraq’s armed forces left a political and security vacuum. Into that vacuum dove looters seeking plunder, arsonists hoping to destroy evidence of the regime’s atrocities and black marketers with a keen sense of what ancient Mesopotamian artifacts might fetch on the open market.

If the anarchy were to persist, experts say, it could drain away the goodwill American and British forces accrued by toppling Saddam Hussein and open the way for political opportunists who could make the job of rebuilding almost impossible.

But the chaos that followed Saddam’s fall must be kept in perspective. Post-war Baghdad, Mosul and other Iraqi cities are in relatively good shape compared with the urban moonscapes that U.S. forces faced following World War II. In Tokyo in 1945, deaths from cholera, dysentery and malnutrition plagued occupation authorities for months as the rotting corpses of those killed in American bombing raids continued to be dug out. During Berlin’s death throes earlier that year, according to the British historian Anthony Beevor, at least two million women were raped by Soviet forces. Some 200,000 of these women committed suicide afterward. The German capital was a city of starving orphans and widows.

The appalling circumstances in Tokyo and Berlin might suggest that the job confronting American troops in Baghdad will be substantially easier. But military officials, politicians and those who have studied past American military occupations say Iraq presents its own set of challenges and that creating a democratic society will require a long-term commitment unprecedented in recent American history.

Unlike Germany or Japan, Iraq is a nation split between two rival sects of Islam, the Sunnis and Shiites, and three major ethnic groups: Arabs, Kurds and Turkomens.

“The major difference between Iraq and the Japanese and German examples is that in those places you had one primary ethnicity to deal with and national identity and civil institutions that pre-dated the governments that launched the war,” said John Dower, an MIT professor who wrote a Pulitzer Prize winning book, “Embracing Defeat,” on the American occupation of Japan.

The danger the United States faces in organizing a provisional government out of these groups, Dower says, is that invariably one side or another will feel that Washington has chosen sides against it — not a problem the U.S. faced in post-war Germany or Japan.

"The behavior of U.S. forces must include a focus on impartiality and on maintaining a credible presence,” says Andrea M. Lopez, a professor who has studied post-war peacekeeping in a variety of conflicts. “Both help with legitimacy, with being seen as a legitimate provider of security while not favoring a specific faction or group.”

This Iraqi cauldron of ethnic divisions makes strife torn Bosnia a more fitting analogy for what U.S. and British forces now face. Bosnia’s Serbs, Croats and Muslims savaged one another other for much of the 1990s before a U.S.-led intervention forced an end to bloodshed. NATO peacekeepers there still maintain a tense peace and in the interim were drawn into an equally bloody ethnic struggle next door in Kosovo in 1999. In both cases, peacekeeping missions intending to stay only a few years have remained in place well beyond expectations.

Paddy Ashdown, the British politician tapped to head Bosnia’s peacekeeping operation in the 1990s, said such situations make democratic reform extremely challenging.

“We made a big mistake here and made a big mistake in Kosovo ... and that was not to realize that the rule of law comes first,” Ashdown told Reuters last week. “We thought democracy came first. We gave this country as many elections as they could (hold) and thought that was making progress,” he said. “You can’t have an operating democracy if there isn’t the rule of law, you can’t have a decent economy, decent politics.”

Yet moving toward any form of democratic rule in Iraq will be even more difficult than it was in the Balkans, experts contend, where at least some democratic institutions existed, dating from the early 20th century. Even Germany and even Japan, Dower notes, experienced periods of parliamentary politics, if not outright democracy, during the century prior to World War II.

What’s more, these nations possessed institutions like labor unions, political parties and private corporations, as well as accountable local government institutions — all of which proved invaluable to post-war American military administrators. Iraq has no institutions with similar instincts to implement policies, let alone formulate them.

“Given the kind of death grip Saddam held over his institutions, it will take awhile — and very good advice — for [Iraqi bureaucrats] to learn how to function as groups of decision making individuals,” said William Turcotte, Chairman Emeritus of the U.S. Naval War College. Turcotte said he encountered a similar lack of initiative among officials from former Warsaw Pact officials after the fall of the Berlin Wall. “There is much in their current behavior learned under so many threats for so long that will make interaction and decisional flexibility extremely difficult.”

The inability of American diplomats to win some kind of sanction from the United Nations or another international body raises another long-term problem: legitimacy.

The fact that the war began with an invasion by U.S. and British forces from Kuwaiti territory has been seized upon by opponents of the occupation both inside Iraq and abroad. American occupations in the past came about very differently. Japan, Germany and Austria found themselves occupied after declaring war on the United States. South Vietnam, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait invited U.S. troops to defend them. The United Nations approved the U.S.-led intervention in South Korea and Afghanistan, and NATO gave its nod in Bosnia and Kosovo.

The unique Iraqi situation, experts say, makes it more difficult to refute those who portray the war as a grab for oil or an Israeli-inspired war against Islam.

“The widely-held opinion that America is merely doing Israel’s bidding and that it just wants to suck Iraq’s oil wealth dry can’t be wished away,” a U.S. intelligence official said, requesting anonymity. “When the Nazis and Japanese militarists fell, their crackpot ideologies went with them. But Islamic extremists offer hope to Saddam’s fans that there will still be a day of reckoning.”

This may embolden foes of the U.S. occupation inside Iraq, said Dower.

“In the eyes of the world, the American occupation of Japan was legitimate,” he said. “There is no such notion of legality in what is going on now in Iraq, and that is bound to make the job more difficult.”

The lack of an international consensus also has made it even more difficult for the United States to counter charges that an underlying motive for overthrowing Saddam is to dole out oil contracts to its own national petroleum giants.

Thomas Pickering, a former senior State Department official and U.N. ambassador who has served both Democratic and Republican administrations, believes that a deep distrust has developed that may take years to dispel.

"I believe the administration when it’s spokesmen say that it’s prepared to use the oil for the benefit of the people of Iraq. But others will question, ‘Well, what’s precisely the way in which that’s going to be done’,” said Pickering, now a vice president of the Boeing Corp. “So, the devil always is in the details. I also believe that, if the U.S. fully supports the principle of using the oil for the benefit of Iraq and attempts to carry that out in good faith, working with the U.N. would put the problem to rest.”

To date, no clear indication of what the U.N.’s role will be has been set forth by Washington. Two weeks since U.S. forces secured the Iraqi capital, the picture remains muddied, with some officials insisting the U.N. will be confined to distributing food and other aid. Others, including President Bush, suggested that a larger role might be in the making. Still, the devilish details referred to by Pickering are nowhere to be found, at least in the public domain.

The nature of defeat

Another complicating factor is what the military calls the “quality of victory” in Iraq. Victory in World War II vanquished America’s enemies along with their ideologies. The context of the Iraqi collapse is very different. Left in place is an overarching sense of ill will throughout the Arab world toward the victorious Anglo-American powers that overthrew Saddam, an animus amplified and exploited by the extremist al-Qaida network.

“Did we win? Damn straight,” said the intelligence official. “Is it over. No way.”

With the stakes in Iraq enormously high, the key question for the occupation may be this: does the United States at the start of the 21st century have the political will to do in Iraq what Gen. Douglas MacArthur did in Japan or what Gen. George Marshal ultimately accomplished in Europe? Does modern America have the stamina and political will to take the casualties and spend the money necessary to see the job through?

To a large extent, the experts say, the Germans and Japanese were well prepared for occupation. The Iraqis are another story.

“You can make excellent policies, but you must have the institutional capability to implement those policies in a way that best suits the needs of the Iraqi people,” said Turcotte. “That will take a very long time.”