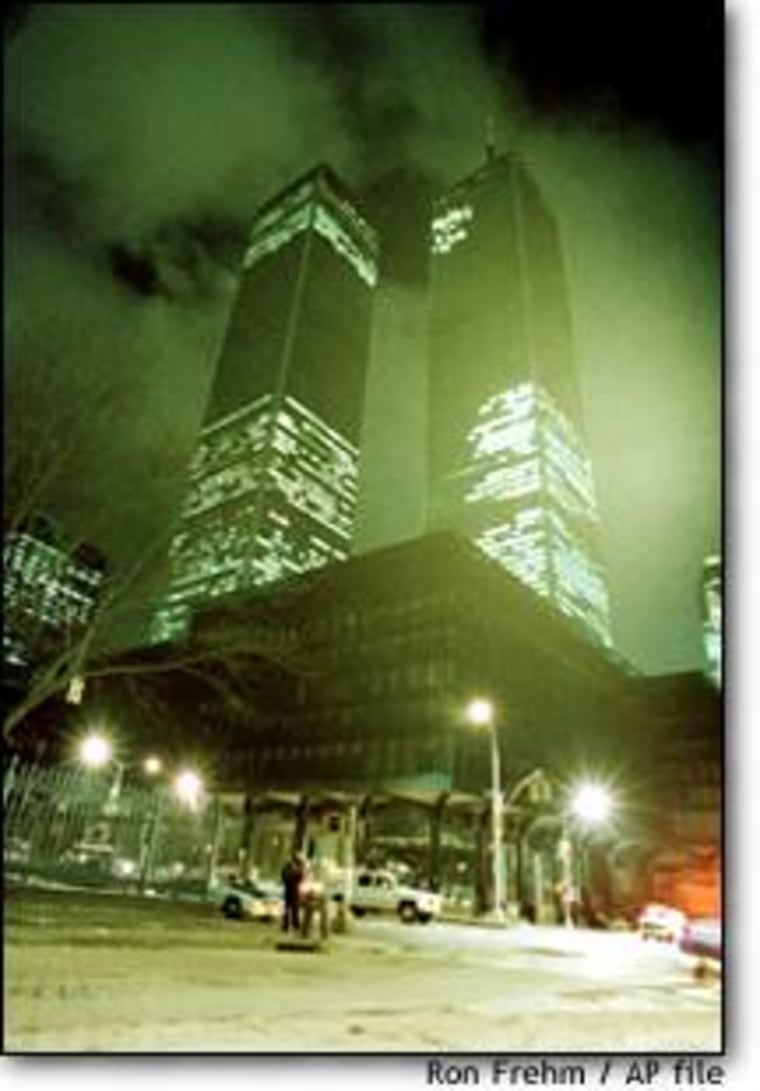

Eight years after what some experts consider the first Islamic terrorist attacks on the United States, the 1993 World Trade Center bombing and the murder of two employees in front of CIA headquarters, terrorists struck again. Stung by the failure of the Immigration and Naturalization Service to foil terrorists, the House has voted to split the agency into an enforcement bureau to catch visa violators and a service bureau to process applications for permanent residency and other paperwork. But some critics say it will still be hard to impossible to track terrorists who enter the country legally.

For years, immigration experts and members of Congress have considered the INS one of the worst-run federal agencies — a view validated by audits by the General Accounting Office (GAO), the investigative arm of Congress.

Critics have assailed the INS for such snafus as mailing out student visa approvals last March to a Florida flight school for the already-dead hijackers of the planes that destroyed the World Trade Center.

INS chief James Ziegler admits his agency has been swamped, even with a doubling in the size of its work force since 1994.

The INS still has only 2,000 investigators to deal with foreigners who are criminals or terrorists, or those who overstay their visas.

“All missions of the INS would be helped if officials in the INS knew exactly what their mission is — whether it is to provide service to immigrants or whether it is tracking down terrorists,” said Deborah Meyers, an analyst at the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington think tank.

“The key, I think, is keeping a link between the two divisions so you don’t have a complete split between those who are tracking terrorists and those who are providing service,” she said. “You want to be able to look at those who apply for some benefit and make sure they don’t have a checkered background.”

First line of defense

Overlooked in the criticism of the INS is the first line of defense against would-be terrorists: the lower-level State Department officials in embassies in foreign capitals who review visa applications from foreigners seeking to get into the United States.

These junior State Department officers bear an enormous — and potentially life-saving — burden. The United States issues more than 7 million visas every year.

The consensus among experts in Washington is that this first line of defense is woefully thin.

Among the recent analyses:

A report by a Washington think tank, the Migration Policy Institute, issued in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks found that “visa processing is assigned to the most junior foreign service personnel. There is little opportunity to build a cadre of knowledgeable and experienced officers skilled in the job of screening for security threats.”

A January 2001 GAO study reported that visa processing is afflicted by serious problems including “staffing shortages, inexperienced staff, and insufficient training for consular line officers.”

A new study by the Brookings Institution says, “The $78 million increase in border security programs in the Bush administration’s 2003 budget proposal is not an adequate response to the challenge of tightening visa processing.”

And tightening visa processing is crucial. If, for example, the U.S. consular office in Saudi Arabia hadn’t issued a visa to Sept. 11 plotter Khalid Almihdar, then he couldn’t have hijacked American Airlines Flight 77 and smashed it into the Pentagon.

In its June 10 issue Newsweek reported that the CIA failed to tell consular officials about Almihdar’s al-Qaida connections.

The news that an American al-Qaida operative, Abdullah al-Muhajir, also known as Jose Padilla, has been arrested in connection with a radiological bomb plot makes the point that keeping foreign terrorists out of the United States is not the whole solution.

But denying visas to operatives such as Almihdar would reduce the risk of terrorists succeeding.

Visa waivers

For citizens of 28 countries — including France, Japan and Great Britain — it is relatively easy to enter the United States because they may come in without a visa, ostensibly for stays of less than 90 days, through the Visa Waiver Program.

The Brookings study reports that the visa waiver system “has been abused by terrorists and other criminals seeking entry into the country, people who would have been disqualified through the normal visa-issuing process.”

Among those who benefited from the program: Richard Reid, who is charged with trying to detonate a shoe bomb aboard a Dec. 22 flight from Paris to Miami, and Zacarias Moussaoui, a French citizen of Moroccan descent, who was indicted last December on conspiracy charges in the Sept. 11 attacks.

The Brookings report urges the State Department to “make a special effort to reduce passport fraud from VWP participant countries. At a minimum, it should ensure that all stolen passports from citizens of VWP countries are entered in the INS database and that all aliens trying to use passports for entry are checked in the lookout database. Stolen passports, or stolen blank passport stock, are often not reported.”

Naturalization process

Another route terrorist conspiracies have used is to employ naturalized citizens to carry out bombings: a recent study by Steven Camarota of the Center for Immigration Studies, a group that favors reducing immigration to the United States, found that six of those involved in the 1993 plot to bomb the World Trade Center and the 1998 attacks on U.S. embassies in Africa were naturalized U.S. citizens.

This suggests another key anti-terrorism role for the INS: background checks and searching interviews of those applying for citizenship.

Another terrorist loophole, the asylum system, has been restricted. On Jan. 25, 1993, Mir Aimal Kansi, a Pakistani who’d overstayed his visa and was allowed to remain in the United States while his application for political asylum was being considered, went on a shooting spree outside CIA headquarters. He was convicted of murdering two CIA employees and is now serving a life sentence.

Asylum “is one area that has been seriously addressed and that process has been reformed,” said Meyers.

New check-in requirement

In a step that will likely end up being more significant to the anti-terrorist fight than the restructuring of the INS bureaucracy, Attorney John Ashcroft last week announced a new entry-exit system, including photographing and fingerprinting of visitors to the United States from five countries: Iran, Iraq, Libya, Sudan and Syria.

The Justice Department said the new treatment would also apply to “certain nationals of other countries whom the State Department and the INS determine to be an elevated national security risk.”

Although the department left this category vague, a draft memo on the topic prepared two months after the Sept. 11 attacks and obtained by NBC News also lists Cuba, North Korea, Afghanistan, Algeria, Bahrain, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Indonesia, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Malaysia, Morocco, Oman, “Palestine”, Pakistan, Philippines, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Tajikistan, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, and Yemen.

Justice Department officials would not comment on whether the list remains the same today. But it seems obvious that some would-be visitors to the United States from the countries from which the Sept. 11 hijackers came — including Saudi Arabia and Egypt — will be subject to the new rules.

If the guests do not check in on the 30th day after entering the United States, their names, photos and fingerprints will be placed on the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) “wants and warrants” list.

Then if a state trooper stops such a visitor because of a traffic violation, he’d check the NCIC list and could notify the INS that he had a wanted person in custody.

But how will INS investigators find the visa violators who aren’t stopped by state troopers for speeding?

The United States has no real-time tracking system for foreigners who enter the country, avoid contact with the police, and have no apparent terrorist connections.

“If you can come in legally and there is no reason for anyone to suspect you, then there’s no reason you can’t commit your (terrorist ) act,” said Meyers.