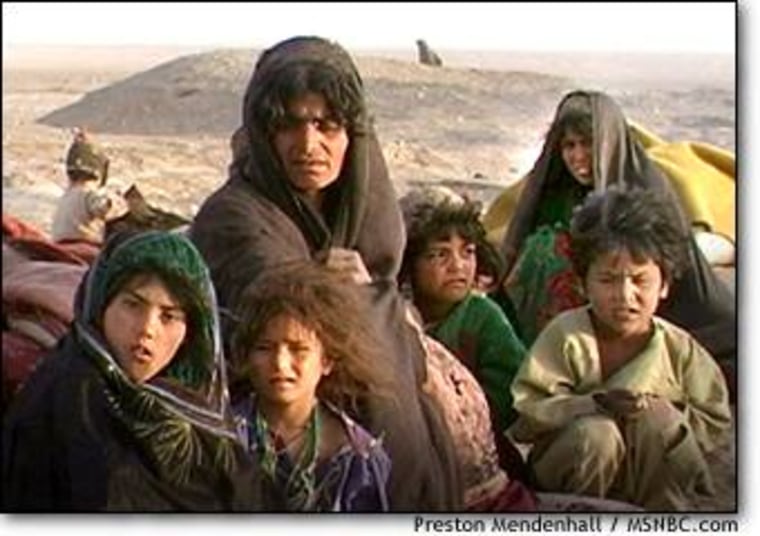

The day the last camel died, Mohammed Nasir knew it was time to flee Afghanistan’s latest crisis: a devastating 2-year-old drought. As harvest after harvest fails on the country’s parched soil, nearly a million Afghans like Nasir are on the move, searching for help from already taxed relief organizations.

Nasir left his village of Zamanzai, in northwestern Badghis province, after more than 1,000 of the village livestock — cattle, sheep and camels — died of starvation.

“There was no grass left,” said the 25-year-old herder, his young face rutted by a life-long exposure to the elements. “We were even mixing grass with our last bit of flour to make it last longer.”

A village dies

The 20 animals that didn’t starve to death were sold for money to buy food. “But when the last camel died, the village men got together and decided we had to go, or risk the same fate as our herd,” Nasir said.

With the last of their money, 100 villagers bought passage out of Zamanzai on the back of a truck. For three days, with no food or water, they sat on blankets in the open vehicle, desperate to reach help at a U.N.-run camp on the outskirts of Herat, in western Afghanistan.

Only hours before rolling into Camp Maslakh, Alya Ghasi, a 25-year-old mother of three, died of exposure and, in accordance with Muslim tradition, was immediately buried — under a pile of stones at the edge of the camp.

The surviving villagers would soon find that their arrival in camp didn’t mean an end to their suffering.

Relief groups overwhelmed

Hundreds of thousands of people like the villagers of Zamanzai are overwhelming already besieged aid organizations in Afghanistan — and in neighboring Pakistan and Iran.

Relief officials say rural Afghans fleeing the drought threaten to cripple the economy and social framework of Afghanistan forever — severely limiting any chance the country has of breaking its near total reliance on humanitarian aid.

“These people slide further and further down the economic scale,” said Stephanie Bunker, a spokeswoman for U.N. operations in Afghanistan. “Landowners become landless, herders become herdless.”

Relief officials estimate that more than 1 million rural Afghans are on the verge of abandoning their land to escape the drought, which has affected almost half the country’s population of 25 million. While the United Nations “begs, borrows and procures” to meet Afghanistan’s emergency needs, Bunker said, “donor fatigue” with the long-running humanitarian crisis has set in.

Donor fatigue sets in

In 2000, the United Nations received less than half the $221 million it hoped to collect from donor nations for Afghanistan. So far this year, it has collected only a third of the money it needs to maintain the marginal existence of the refugees.

U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell has announced a $43 million emergency aid package to help Afghans through the severe drought. But aid workers fear that may be too little, too late.

Hans-Christian Poulsen, the U.N. relief coordinator for western Afghanistan, said help from the “outside world has been quite limited, especially when you think of Kosovo.”

In Afghanistan, international donations average about $5 per person. During the Kosovo refugee exodus, they averaged $100 per person. So unlike the hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing Kosovo to neighboring Albania, the villagers of Zamanzai were not greeted with bottled water, apples, oranges and blankets when they arrived at Camp Maslakh.

The 'OBL' factor

Added to the donor fatigue is the worldwide opprobrium for Osama bin Laden, Afghanistan’s most infamous resident, who Washington accuses of masterminding terrorist attacks on U.S. interests.

U.N. officials say the U.S. focus on bin Laden has had a negative impact on their diplomatic and humanitarian efforts in Afghanistan.

“We call it the ‘OBL factor,’” said Yusuf Hassan of the U.N. High Commission for Refugees.

But OBL and donor fatigue are abstractions in Mohammed Nasir’s world.

Another night without food

Because they arrived too late in the day to register with the camp’s distribution center, Nasir’s family spent a fourth night without food. They got water from a camp well and sprinkled tea in it for flavor.

The following morning, Nasir and a village elder, Abdul Aziz, set out to get flour from a camp warehouse. But they were turned away because their families had not received vaccinations against common diseases. Aziz and Nasir rounded up all 100 villagers and joined a line of other recent arrivals outside the medical tent.

The clinic closed before their names were called. “What are we supposed to eat, dirt?” asked Aziz.

They spent a fifthnight without food, huddled together against overnight temperatures that dropped to 40 degrees.

They also spent the next day huddled together, this time in the paltry shade of blankets and shawls fashioned into small shelters, desperate for relief from daytime temperatures that soared to 100.

Exposure had already claimed more than 150 lives in Camp Maslakh. Three elderly villagers from Zamanzai sat motionless, without moving for two days, and the group expected their burials to be next.

Promised provisions aren't delivered

Near what would have been dinnertime on their sixth day without food, Nasir located another villager, named Bashar, who had fled with his family two months before. As Zamanzai’s latest arrivals listened to Bashar’s account of camp life, the looks on their faces betrayed fear.

With the aid of a cousin and an old English dictionary, Bashar had written a letter to the United Nations — “or anyone,” he said, and was looking for somebody to deliver his plea. “My defficult is very much and we have a complicated problem. Our problem is food,” Bashar wrote. Despite a U.N. goal to provide each refugee with 15 pounds of wheat every 40 days, Bashar said sometimes it was only delivered every 60 days.

“We didn’t see anything — no oil, no rice,” the letter said.

‘Presented with Bashar’s appeal at his office in Herat, the U.N.’s Poulsen gave a weary shake of his head. “The influx we have right now is so huge that it is difficult to provide for these people, even to provide sufficient food for new arrivals,” he said.

As the villagers of Zamanzai neared the end of their first week in flight from Afghanistan’s latest crisis, they still had not eaten.

“We have nothing. We don’t have flour. Our kids are dying from hunger and thirst,” said Hur, a woman who didn’t know her exact age. “Give me some food or kill me.”