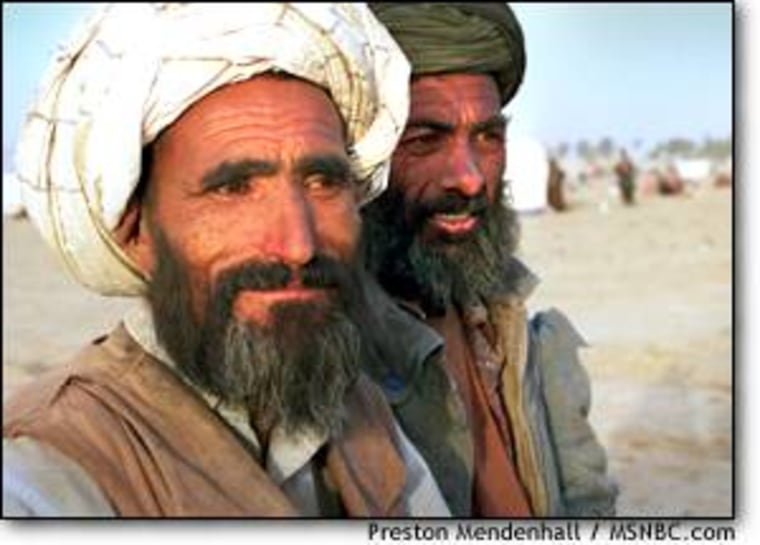

This country lies in ruins and its people suffer from the physical and psychological trauma of 22 years of war. But almost all Afghans have one burning question for a rare foreign visitor: “Are you enjoying yourself?” It threw me. I stumbled over my words, offering windy explanations of American politics and Osama bin Laden. Until I realized that nobody cared. Only one response pleased Afghans, who were really searching for evidence that their country still had something to offer. When I answered, “Yes,” my hosts’ eyes lit up and they smiled proudly.

The invading Red Army flattened their cities, and warlords pillaged what was left. A seismic refugee exodus is in its third decade. And there is no surface in the country that can correctly be described as a road. Still, Afghanistan is a land of unparalleled beauty and hospitality. And Afghans take enormous pride in this.

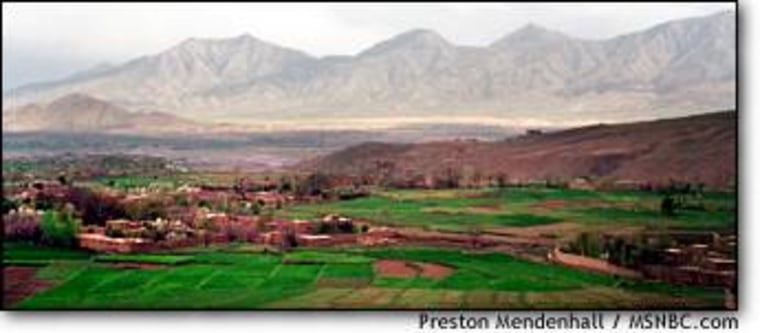

The scenery itself is stunning. Descending from the snow-capped Khugrar Pass into Jalalabad, you see much of what centuries of conquerors came for — a stronghold in Central Asia, fertile plains and mineral-rich mountains. When you turn and look back over your shoulder, you wonder how the Soviets ever thought they could send tank divisions over the Khyber.

Landscape scarred by poverty

But lower your eyes and you see the pain of the people. Along Afghanistan’s roads children toss dirt into potholes, hoping to earn a 10,000 Afghani note, about 9 cents, from passing drivers. They stand for 12 hours a day, often in areas with no village or town visible in any direction.

A closer look at the landscape reveals that almost every tree in the country is missing all but the top branches. The rest have been snapped off for firewood. No public park or shady boulevard has been spared.

Afghanistan is in survival mode. Nobody earns more than a few dollars a month, if that. The Taliban, the Islamic regime that has ruled the country for five years, is occupied with a war up north. So government ministries are open from 8 a.m. to noon. Workers have little to do but sit and drink green tea in darkened rooms.

Future wins over past

For my few days in Kabul, the Taliban required me to hire a government “guide” — a minder who was supposed to make sure I didn’t stray into any private homes. He would proffer friendly observations, like: “This road used to be asphalt.” But when I asked him when the Taliban captured Kabul (1996), he was off by a year.

Afghans appear to be happy to leave their past behind. Not surprisingly, in fact, most keep one eye fixed firmly on the future. On the once-grand campus of Kabul University, where the sun streams through the hacked-off limbs of tree-lined promenades, I met Hasibullah, an 18-year-old wearing the turban required by the Taliban and a worn-out pair of sandals.

A fourth-year student on the medical faculty, one of the few functioning higher education institutions in Afghanistan, Hasibullah was eager to share his dreams. “I will first become a general practitioner. In another three years, I will be a surgeon,” he said in broken English.

Never mind that medical students have few textbooks, sleep 16 to a dormitory room built for four and have no laboratories where they can gain practical experience. Hasibullah was still determined to be a doctor.

‘I’m happy to see you!'

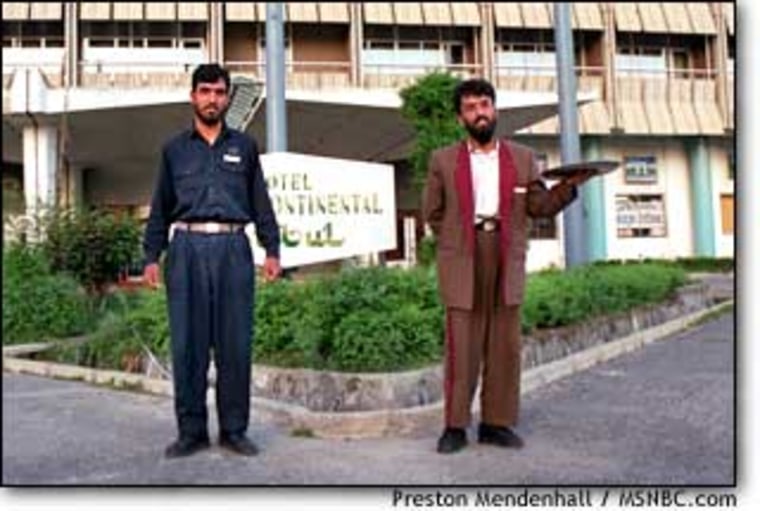

I found that same resolve just about everywhere I went. Especially at places like the Intercontinental Hotel in Kabul. Perched high on a hill with a commanding view of the Afghan capital, the Intercon was journalists’ the hangout during the Mujahideen days.

Today, the Taliban rulers force all correspondents to stay at the Intercontinental, which provides about the only source of foreign currency to the government. The hotel has a new mullah manager trying to make the best of a bad situation. At the beginning of my stay, seven of the 200 rooms were occupied. On the last night I was one of three guests.

A bellboy was kind enough to turn lights on and off — saving scarce electricity — as I walked down the hall to my room. “I am very happy to see you!” Shah Mamoud said, grinning. I really think he was. It wasn’t a tip he was waiting for, although he certainly got one. After 30 years working in the hotel under various governments — first under a king, then a communist, then a warlord and now the Taliban’s leader, Mullah Mohammed Omar — Mamoud said he was just happy to see a guest.

Kabul's main attraction

Downstairs in the lobby, the staff is on guard on Fridays, a traditional Muslim weekendday when militant Talibs look for something to do with their free time.

It turns out the Intercon is one of Kabul’s main attractions. Many Taliban fighters back from the front have never seen such luxury — even the bullet-scarred and crumbling hotel that the Intercon is today. Because of the commotion caused on previous visits, hotel security kept the fighters outside during my stay. They stared fascinated at the Intercon’s revolving front door.

I was sad to check out of the Intercontinental, although it was the first time I ever had to pay an 8-figure hotel bill. Luckily, the clerk allowed me to settle my 32 million Afghani account in dollars, 440 in all. I would have needed a wheelbarrow for all that cash.

With the occupancy rate dropping exponentially with my departure, the staff decided it was time for a traditional Afghan embrace — all eight of them on hand to check me out at 4:30 a.m. “Did you enjoy Afghanistan?” they asked.