Every day, the miners trudged to the gold mine outside Watsa, a remote village in mineral-rich eastern Congo. In April, a few complained of headaches, fever and breathing problems. The next day, they experienced violent diarrhea and began vomiting. The village began to question the local doctor’s diagnosis of malaria. Their fears were confirmed a few days later when the first victim died.

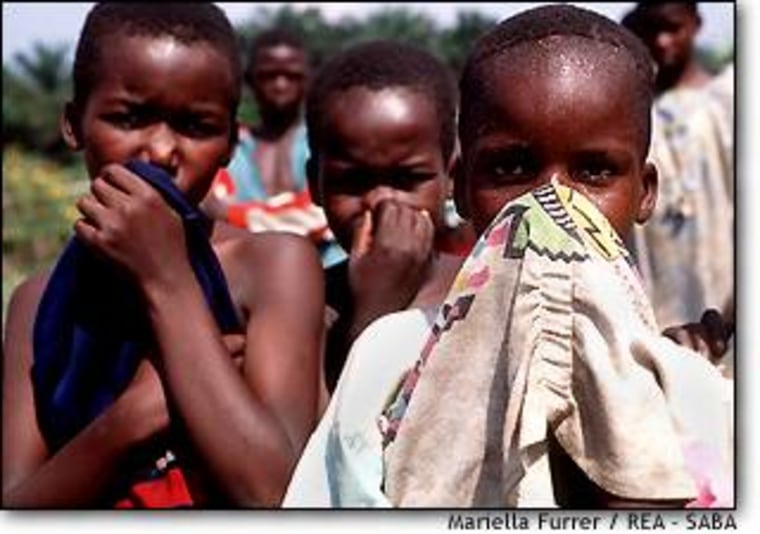

As is often the case in Africa, word of the mysterious disease traveled slowly. Roads in eastern Congo are impassable; telephones are non-existent. When foreign doctors finally arrived in Watsa, they found a full-fledged outbreak of a disease from which few recovered.

Laboratory tests confirmed that the miners had contracted Marburg, a deadly virus that attacks human cells and causes massive bleeding throughout the body. At least 60 died.

Such stories once caused more curiosity than concern outside of Africa, a continent stereotypically portrayed as backward, untamed and anarchical.

If those labels no longer apply to the continent, they still apply well enough to African health care. Epidemics can rage unchecked. Treatable diseases claim tens of thousands yearly.

And in a word made smaller by air travel and immigration, it is unlikely that these diseases will remain confined in Africa.

For a variety of reasons - climate, lack of infrastructure, poverty and illiteracy are just a few - Africa is viewed by many of the world’s leading health officials as a prime breeding ground for problems that cannot be quarantined. The AIDS epidemic, believed by most scientists to have originated in Africa, is the classic example.

Another may be this summer’s mosquito-born outbreak in New York City of West Nile virus. Such incidents have led the United Nations, the U.S. National Institute of Health and Europe’s health ministries to conclude that Africa’s infectious diseases could pose a threat to the globe in the coming century.

Mysterious beginnings

Marburg, like many diseases born in Africa, is believed to have started in the continent’s central dense forests. That’s just one of the traits it shares with its better-known cousin, Ebola. Known as hemorrhagic fevers, both are among the most virulent viral diseases known to mankind. The early symptoms are similar: high fever, headaches, stomach pains. Neither has a cure. Most cases end in death.

Little else is known about the diseases. Mammals, especially rodents, appear to be important natural hosts for many hemorrhagic fever viruses. But the animal hosts of Marburg and Ebola are undiscovered.

The Marburg virus, which has an incubation period of two to 21 days, was first recognized in 1967 in an outbreak of a hemorrhagic disease in the German city of Marburg. That outbreak was linked to the importation of African green monkeys to Germany.

A decade later, in 1976, the Ebola virus, named after a river in the Congo, the former Zaire, was first identified after two epidemics that killed 397 people in western Sudan and eastern Zaire.

In 1989, the Ebola virus was isolated in monkeys imported from Philippines and quarantined in U.S. laboratories. A large epidemic in western Zaire in 1995 claimed 244 deaths, and was followed by another outbreak in the country of Gabon in 1996. In all, at least 793 people have died from Ebola.

Crossing species

One theory suggests that a plant virus may have led to the animal infections. From there,

a

n infected tick or mosquito can transmit the disease to humans. And Ebola is then transmitted from human to human via blood, secretions or semen.

Hemorrhagic fevers have also been transmitted via the handling of infected chimpanzees, a particular problem in many parts of Africa where the bush meat trade flourishes.

Poaching of bush meat - from reptiles to primates - is big business in countries like Congo and Cameroon. Heaps of roasted monkeys and antelope parts from the nearby jungles fill markets in Yaounde, capital of Cameroon.

Logging companies assist in the bush meat trade. While their workers rely on bush meat for food, logging roads allow hunters to reach remote areas of the forest, and trucks provide an efficient mode of transport. And experts warn that people encroaching further on the forest in search for food are bound to soon unearth other deadly diseases.

Because these hemorrhagic fevers occur in localized outbreaks in remote areas, finding a treatment is difficult. Epidemics are severe, yet they happen infrequently, and there are only limited opportunities to gain new insight into the clinical nature of the diseases.

Pat Campbell, a doctor with Medicins sans Frontieres, noted the toll in Africa has extended to health workers as well.

“The doctor in charge of the hospital in Watsa - to which a number of cases had been referred - died of Marburg virus infection,” she said. “Thereafter, patients shunned the hospital, believing that certain employees of the hospital had used witchcraft to cause his death.”