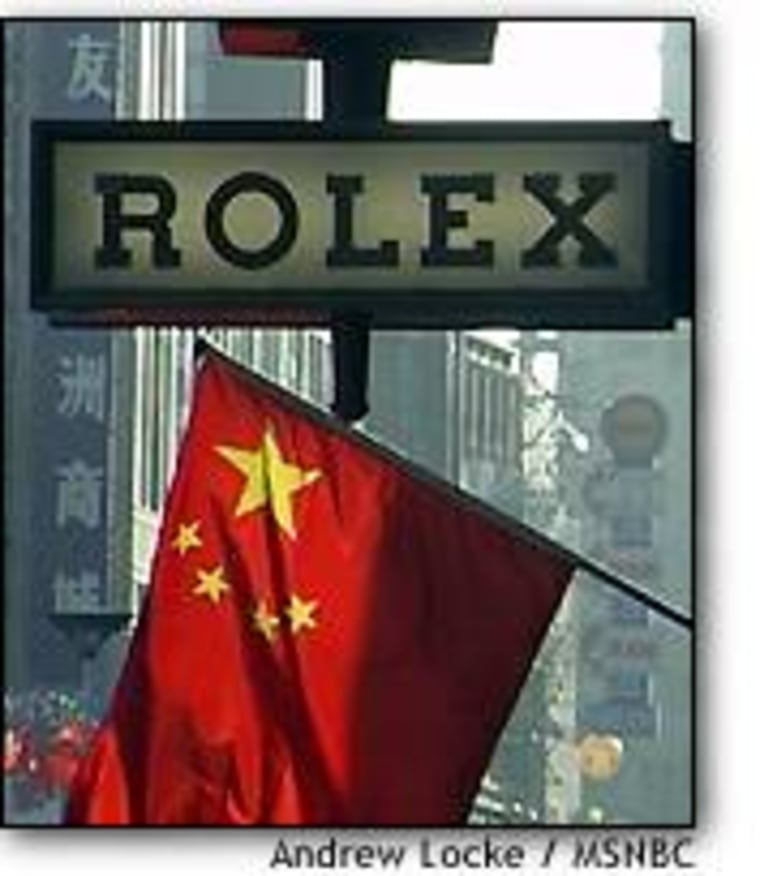

“Long live Marxist, Leninist Ideology, Mao Zedong Thought and Deng Xiaoping theory!” reads a banner on a department store, paying tribute to the heroes of the last 50 years. But here on Nanjing Road, new icons have crowded in: signs touting Cartier, McDonald’s, Mickey Mouse, Remy Martin and Hello Kitty scream for attention. Shanghai, more than any other place in this vast nation, looks like the face of China’s future.

Once again, Shanghai has become what it was when the Japanese troops overran it in 1937: a vibrant, economically powerful and cosmopolitan port city.

The grand old banks on the city’s most famous boulevard, the Bund, are under renovation, being readied for clients like JP Morgan and Hong Kong Shanghai Bank who fled in 1949 after the Communist takeover.

Foreign and domestic investment to the city has relit its flame. The new money has led to new cultural institutions, karaoke clubs, cell phones, health clubs - even a thriving district of gay bars. A downside exists, as well: Prostitution and street crime have increased, as has drug use. In other words, Shanghai has many of the ills of any other normal great city.

Fashion and finance

Not all of its population of more than 14 million is sharing in this new wealth, of course. But the sudden emergence of a Chinese city as a world fashion center, for instance, is striking. The cityscape is rife with vinyl miniskirts, clunky platform shoes, dyed hair, tattoos and gravity-defying breast implants.

The commercial energy of the city is almost overwhelming. Everyone seems to be in business. Scruffy street vendors hawk pirated video discs. New releases, like the Stanley Kubrik’s Eyes Wide Shut, go for just about $3.

Tony Zhang, a 32-year old Shanghai resident who lived in the United States for many years, runs Park 97, a chic new tapas bar and club in Shanghai’s Fuxing Park. His next business, Zhang told MSNBC, will be a Web site. Here, it seems everyone’s “next big deal” is in Internet content, ISPs or e-commerce.

“Entrepreneurship is in the blood of the Shanghainese,” Zhang said.

Shanghai reborn

Despite its freewheeling appearance, the rebirth of Shanghai is relatively recent. In the early 1980s, when economic reformer Deng Xiaoping was launching his first capitalist experiments in parts of the southern Guangdong Province, Shanghai was a decade away from real reform.

It was not until 1992, after Deng took a trip south from Beijing - a landmark that became known as his “Southern Tour” - that Shanghai got the green light on economic reform. Deng had toured the special economic zones in Guangdong and was pleased. With a few cryptic remarks in Shanghai, the emperor lit a fire under its economy.

Even today, the city still has far more socialist overtones than that of the reform in the South. Planners took to heart Deng’s dictum that the whole country should contribute to making Shanghai the “dragon’s head” of the economy. In five years, they have built an entirely new city, Pudong New Zone, on the riverbank opposite the old Bund, overseeing one of the biggest building booms in history.

Pudong has Stalinist aspects: the world’s third tallest television tower, one of the tallest hotels in the world, a whole new downtown filled with skyscrapers and wide boulevards uncluttered by the hustle and bustle of street commerce. Disregarding the market, provincial governments poured money from their coffers into trophy buildings in Pudong as well, contributing to what is today a massive glut of office space. About 70 percent stands vacant.

“Deng said Pudong is the place to support, so money flowed to Pudong,” said a Chinese financial professional with unconcealed disgust. And the trend is unlikely to change soon - both President Jiang Zemin and Premier Zhu Rongji are former mayors of Shanghai.

The invasion

Foreign companies saw it as an act of good faith to invest in Pudong as well, quite aside from the facilities it offers. In the area are some of China’s most advanced plants, run by companies like Bell South, General Motors and electronics producer Sharp.

Shanghai’s north end is home to its old industry - heavy, polluting chemical, steel and textile plants that have struggled in the face of new competition. There is a gradual effort to move these plants out of the city, but it is an expensive problem, and there are thousands of workers to deal with.

In the meantime, visitors are discouraged from visiting that part of the city. During the just-completed Fortune 500 conference in Shanghai, all riverboats that normally pass through the old industrial area were off limits to tourists. Pudong is the Shanghai officials like to showcase. It represents what they hope is their future - clean and orderly.

Focus of revolution

Shanghai’s trek to 1999 has been even more troubled than that of most places in China. Prior to the revolution, extreme wealth concentrated in a few hands lived alongside crushing poverty. To its detractors, Shanghai was more like Calcutta than the “Paris of the East.”

Shanghai also represented humiliating foreign control in China. Since the 19th century, large sections of the city were occupied and administered by Western and Japanese concessions, off-limits to average Chinese. After 1937, Japan’s army took complete control and imposed a brutal regime here.

Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that it was in Shanghai that a tiny group of young reformers, including the young Mao Zedong, held their first secret meetings. It was the beginning of several decades in which Shanghai became a stronghold of the most hard-line of China’s Communists. The infamous “Gang of Four,” including Mao’s widow Jiang Qing, was based here and in the late 1970s made their final stand against plans for economic reforms.

Late bloomer

Today, with the notable exception of the old financial buildings on the Bund, much of the old architecture of Shanghai has been destroyed. But if you wander around the city on foot, you can an occasional glimpse of old mansions tucked away behind the newer buildings. Most have gone to seed, subdivided by many families over the years.

And far from the gleaming streets of Pudong, the life of a very different metropolis goes on. Tucked away in a suburb near the old airport, the oldest profession in the world thrives. The neon-lit Starlight Karaoke Club - like scores of other clubs - is teeming with sultry “hostesses” who entertain men in private singing rooms. Lining the street are barbershops packed with female hairstylists who cut very little hair.

Many of these women are from the countryside, coming to Shanghai for a share in the action. Tens of thousands of laborers have also come to get in on the building boom. Many of them will try to stay.

“Shanghai is cool,” said a young man from Jiangsu as he stood on the Bund gazing at the gigantic Pearl TV tower on the other side. “There’s so much to do.”

The mix, in the end, is neither Shanghai of past glory, nor the socialist ideal of the future, but an amalgam. Add a sprinkling of Disneyland and a dash of New York, and the true picture of China’s leading city becomes nearly complete.