As the vast and unmanageable land it is, Russia would seem ripe for massive urban migration. A handful of large cities suck up almost all post-Soviet investment in the country, leaving nothing for rural regions. Life on the farm — and in Russia’s smaller cities and villages — is miserable and desolate, with low or no salaries and poor living conditions. Entire local economies disappear as industries fail to keep pace with the emerging market economy.

Yet in a time of economic desperation, when workers are owed months - and sometimes years - of unpaid wages, Russia’s rural population has largely stayed put. The dumb luck of Russia’s market reformers has made it nearly impossible, legally and economically, for the rural population to migrate to booming urban areas. Millions of rural Russians living in far-flung regions can’t even afford the bus fare to the nearest city, let alone find housing and jobs in an economy that is not growing.

Meanwhile, migration and land reform experts watch the country closely, quietly analyzing its population movement and rural economies. They hope continued dumb luck - and some well-placed rural economic programs - will keep the rural population from overwhelming urban areas until the Russian economy recovers from post-Soviet depression.

Exiled on the farm

Inkino, a Siberia village of 1,000, typifies the Russian rural landscape. A victim of strongman Josef Stalin’s forced collectivization of agriculture, Inkino was “settled” under the orders of Soviet central planners in 1933. Two hundred miles from Tomsk, the region’s capital, and 2,000 miles from Moscow, Inkino was once thick Siberian forest, but settlers cleared the trees and set about coaxing crops from an inhospitable land.

Seven decades later, the failure of Stalin’s great collective farming experiment is well known. Inkino should be a ghost town; the village’s one employer - still the collective farm - is insolvent. One in every third person is unemployed.

Thirty-year-old Olga Kuzmina was born and bred in Inkino. Her grandparents were some of the first to arrive in the 1930s. A teacher in Inkino’s only school, Kuzmina, who hasn’t been paid in 16 months, has thought many times about leaving, but then decided against it.

“So many people have tried to leave Inkino … but they all come back,” Kuzmina says. “Our neighbors moved to Orenburg (a city 1,000 miles away) twice - and they are back again. They couldn’t make ends meet in the city.”

Bread for gas

Like many Russians, Kuzmina and her husband, Mikhail, can barely make ends meet. Mikhail works as mechanic on the farm. He longs for life outside Inkino. “All I would need is a job and a reasonable place to live,” he says. “But my house here is only worth about $1,700. That won’t buy anything in Tomsk. And besides, you need money for the future,” Mikhail says.

Inkino’s economy is nonexistent. The only people who earn cash in town are “budgetniki” - teachers, doctors and local officials paid, albeit infrequently, from the state budget. The farm stopped paying wages years ago, and now only pays in kind. The workers are left to barter the farm’s products for life’s necessities. Fish are traded for gas, gas for vodka and vodka for flour - and on and on until residents of Inkino get what they need.

There is no cash even to buy a ticket out of town. The buses to Tomsk won’t accept a pound of tomatoes for a ride.

But even if the resident’s of Inkino could put together enough money to make it out of town, many Russian cities wouldn’t have them.

Locked on the land

Russia’s cities - with the tacit approval of the federal government - employ a combination of administrative impediments and heavy-handed enforcement to keep people from crowding big towns. Given the depressed Russian economy, with no growth for the last seven years, cities struggling to provide for their current populations can hardly welcome new rural residents.

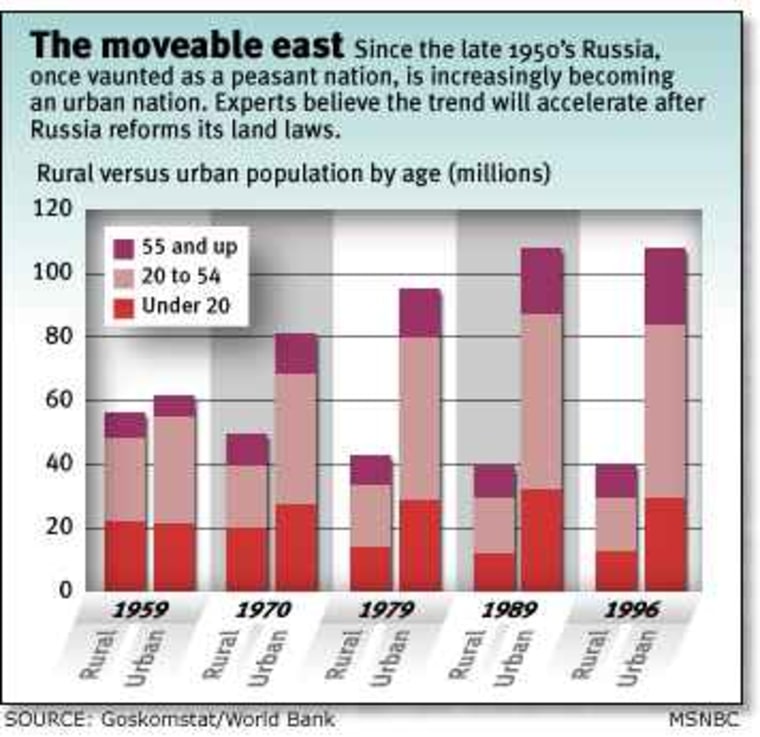

But big problems are afoot. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, more than 80 percent of Russian farms are insolvent - which means a large percentage of the 40 million strong rural work force is in danger of losing their jobs. Between 1990 and 1996, Russia’s gross agricultural output fell continuously - 36 percent in total, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the Paris-based organization of 29 industrial countries that promotes economic growth in developed and developing nations.

Beginning in 1991, though a series of privatization decrees and legislation, the Russian government transferred land shares from its vast Soviet-era collective and cooperative farms to individual workers. But two pesky coups and intense economic turmoil stalled the passage of a Land Code to govern the new land market. So while rural landowners can own land, they cannot sell, trade, mortgage or will their plots.

Meanwhile, much like in Inkino, millions of shareholders have leased their property to big farms that resemble Soviet-era collective enterprises, and continue to work the land. But the large farms are sick. Lacking the capital to reform, they limp along on the verge of bankruptcy.

Unhealthy agriculture

“Big farms do not offer any advantages to Russia at present, except under some exceptional circumstances,” says Wold Bank land reform expert Karen Brooks.

Nonetheless, big farm bosses are trying to “corporatize” the agricultural sector - a word that strikes fear in the hearts of migration experts. A few red rural bosses aim to run massive farms, and to turn workers into investors rather than simple lessors, inducing employees to sell their shares. Large farming enterprises currently are lobbying the Communist-dominated Duma, Russia’s Lower House of parliament, to pass a Land Code that promotes corporate farming. Lawmakers continue to pass Land Code revisions that place multiple restrictions on property ownership, which President Boris Yeltsin vetoes repeatedly.

“Once the corporation has ownership of the land, it can readily dismiss workers deemed to be redundant,” Brooks says. “The workers would have to find alternative employment, and little is available in rural areas.” To combat this threat, the World Bank has invested over $200 million in technical assistance and land rights education projects in the Russian agricultural sector.

Farmers, and rural workers who hold jobs related to the agricultural industry - estimated at 50 percent of the total rural population - could head for urban areas. But even if millions of rural residents do lose their jobs, they won’t be welcome in many Russian cities.