It wasn’t long ago that the great Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes penned an homage to his national capital’s breathtaking beauty — “a region of transparent air,” he wrote. These days, North America’s largest city barely breathes at all. Not only is pollution is suffocating Mexico, but crime, overcrowding and a collapsing infrastructure threaten it as well. Nonetheless, a population hovering at the 20 million mark still regard it as the right place to be, something that frustrates those trying to deal with the capital’s many ills.

“Tenochtitlan,” as it was known to the Aztecs who founded the settlement, was a meeting point and a center of politics and religion. But life here was never simple. The city, crossed by rivers from south to north, was often flooded. Earthquakes leveled its buildings over and over. But the Aztecs wrote off those disasters as the work of angry gods. Over the years, that determination to stay on despite adversity became a national trait.

Destination number one

When Camilo and Alicia decided to leave their farm in the Mexican state of Puebla, the obvious place where to start a new life seemed to be Mexico City. The piece of land they owned for ten years could no longer support their family of five. They had no money for seed or fertilizers that year and the only loan they could manage to get was just too risky.

So they sold their small property, grabbed a few things and left the peaceful farm for the raucous metropolis. Alicia, looking back, says that part of their identity was lost forever that day.

In Mexico City, the Lopez family found a room in a quite decent neighborhood but one that seemed too distant from everything they needed. After living in the countryside all their life, they had a hard time to get used to urban realities like commuting, traveling to distant shops or other neighborhoods to do business.

“When I realized I had spent half of our savings, and still I didn’t have a job, I decided it was about time to get a place at a street market, and sell tacos”, Camilo said. ”Chilangos live on the streets.”

Chilangos, as Mexico City residents are sometime known, do live on the streets. Early in the morning on any corner here, it is common to see Mexicans having breakfast on the streets. As the day goes by, that corner will become host all kinds of activity: vendors hawking drinks, socks, t-shirts or any type of food. They all buy and they all sell something, as if they were trying to maintain some mysterious equilibrium. Paintings depicting the city in pre-colonial times and through the Spanish period show much the same scene.

The story of Camilo and his family is ageless, but as the 20th century draws to a close, the situation may be reaching a critical mass. According to the U.N., by 2000 almost half of the world’s population will live in urban centers, with rural areas suffering enormous depopulation and the collapse of traditional cultures and economies that go with it.

Meanwhile, Mexico City’s population grows by more than three per cent each year. Puebla, Oaxaca, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Michoacan and Veracruz — rural, mostly poor states — funnel a seemingly endless supply of new blood into the capital.

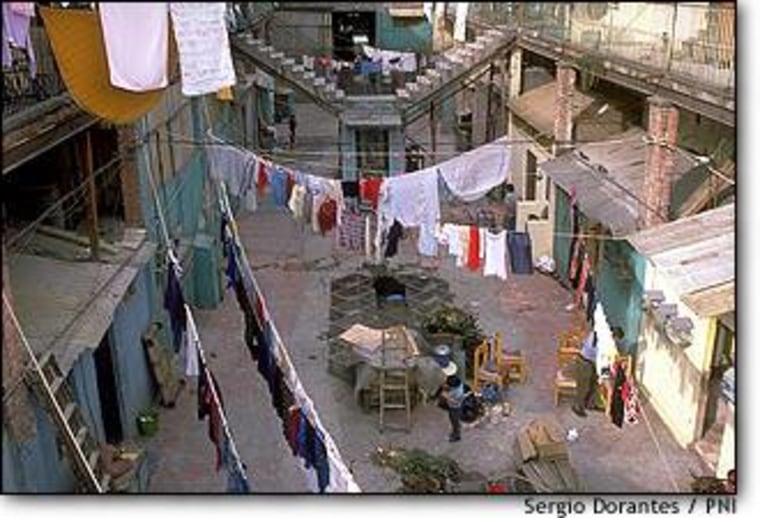

More than 70 per cent of the migratory population here lives in marginal areas — many little more than shanty towns. These districts have reduced access to education, health care or even clean water. Living standards of this group are miserable, with the accompanying implications for morbidity and mortality. For millions of families in Mexico City, elementary needs for survival are simply not met.

Two Mexicos

Sitting uncomfortably in the center of this human flood is the modern capital of a striving young nation. Mexico City is very much a place with two realities that don’t often interact. While a part of the city has access to the latest technology and comfort, the other, far greater portion doesn’t dare dream of such things.

Camilo, the Puebla farmer, determined this quickly, giving up his aspirations of getting a stable job and joining the informal “street” economy. His wife, Alicia, was luckier. She got hired as a maid at a house in Lomas, a “luxury ghetto” surrounded by armed private guards. With a 39 percent increase in crime since the New Year, such communities are increasingly popular among the rich. Robberies are not only more frequent but also more violent. Sadly, once placid Mexico City now ranks among the ten most dangerous places in the world.

The statistical tale of woe has many experts worried about a complete collapse if things don’t improve. For instance, U.N. officials believe the city has the worst air pollution in the world. The crime wave is eroding already difficult living conditions. The informal economy produces more than six million tons of garbage per day, much of which just sits where it falls.

The most serious and immediate crisis may be the water supply, which is simply not sufficient for the overcrowded city. So much water has been pumped from Mexico City’s aquifer that buildings sink by as much as a foot a year in some districts.

Unlike the Aztecs, Mexicans don’t view these ills as a demand for sacrifice from the gods. Yet still the population grows, even as many stream north in search of a better future in America.

Laura Saravia is an NBC News producer based in Mexico City.