As political forces position themselves over war with Iraq, the forces of global business have also been positioning themselves. Even U.S. companies are among those with business interests in Baghdad.

He sits atop the world’s second largest oil reserves. His country is in desperate need of just about everything. In short, Iraq is one huge business opportunity.

“In addition, there’s roughly 220 billion barrels of oil we think Iraq has that it hasn’t discovered yet, said John Felmy, chief economist at the American Petroleum Institute.

Some American companies have already been doing business with Iraq, though often indirectly: oil companies like ChevronTexaco and ExxonMobil sometimes buy Iraqi oil through purchasers in places like Russia, and then bring it to the U.S. to refine.

“So far this year, we’ve imported about 500,000 barrels a day from Iraq,” said Felmy.

It’s all there in print: in SEC filings like a recent one by Texas-based oil refiner Valero, reporting that some of its crude originates in Iraq.

Experts say oil services companies like Halliburton have equipment ending up in Iraq — sometimes through foreign subsidiaries or sometimes through foreign countries like Jordan or Syria.

“Those countries border Iraq, and they have been trading with Iraq throughout the last decade,” said Josh Spero, a former Pentagon strategist.

Even General Electric, the parent of CNBC, has been doing some trade with Iraq. (GE is also the parent of NBC, Microsoft’s partner in MSNBC.com.)

How can this be? First, a little history. Go to the and you’ll find a copy of a 1987 cooperation agreement promising trade, especially in technology, between the U.S. and Iraq for at least five years.

But then came the invasion of Kuwait — and the Persian Gulf War.

All trade was cut off until the late 90s, when the United Nations approved an oil-for-food program, allowing Iraq to sell oil in exchange for necessities.

Under this program, some American companies have done business with Saddam’s regime. ChevronTexaco and ExxonMobil both told CNBC in statements that all oil they’ve bought has been acquired under U.N. rules and U.S. law. GE tells us, “what we do is supply equipment and spare parts for power generation, oil and gas in Iraq ... all under the U.N. program. The company has commitments there and is continuing to meet them ... it is a relatively insignificant amount of business.”

But Spero, who has worked on counter terrorism for the U.S. joint chiefs of staff, says tensions between the U.S. military and U.S. business soon became evident after the oil-for-food program began.

“Saddam Hussein’s government has siphoned off some of the profits of trading oil and has rebuilt parts of his military with the money,” he said.

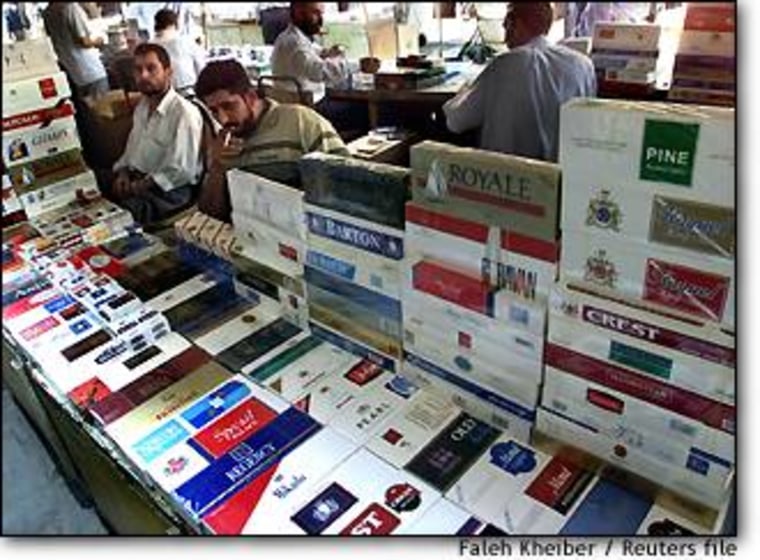

And then there’s this twist: while some American companies have done some business involving Iraq, U.S. allies are way ahead in doing business. Last month, at the annual Baghdad International Trade Fair, more than 1,200 companies showed up — the largest turnout since the Gulf War — including companies from France, Germany, and Italy. None came from the U.S.

Many who attended say they came to get in on the ground floor in signing contracts, especially if there’s a regime change. That means that if American troops do come in and topple Hussein, American businesses may be the last to profit. Daniel Yergin, Chairman of Cambridge Energy Research Associates, says that assumes a lot.

“Would those contracts be valid? Are they contracts signed with the sovereign state of Iraq or are they signed with the regime of Saddam Hussein,” he said.

U.S. oil companies are cautious about putting too much faith in opportunities of any kind in Iraq because of what happened in Kuwait. After Iraqi troops torched Kuwaiti oil fields at the end of the Gulf War. Kuwait promised it would seek foreign investment to rebuild and expand production. Those promises went up in smoke.

“Sometimes good intentions don’t work out,” said Yergin.

Last week, the U.N. Security Council voted to extend the oil-for-food program another six months. But there is friction over what products should be allowed. Many products can have duel purposes. For example, Siemens has sold Iraq medical components that help break up kidney stones — but those same components can be used as triggers for nuclear bombs.

Now the U.S. and Russia are at odds over what the U.N. should allow to be sold under the program.

And finally, there’s the possibility that nothing will change: there will be no war and Saddam will stay. France, Russia and China have oil contracts with Iraq that would become operational if sanctions are lifted. All three just happen to have veto power on the U.S. Security Council, giving them a distinct advantage in profiting from a country that has vast potential — with or without Saddam.