A special trust set up by American Airlines’ top executives will allow them to collect retirement benefits regardless of whether the airline goes bankrupt, according to documents filed by the company.

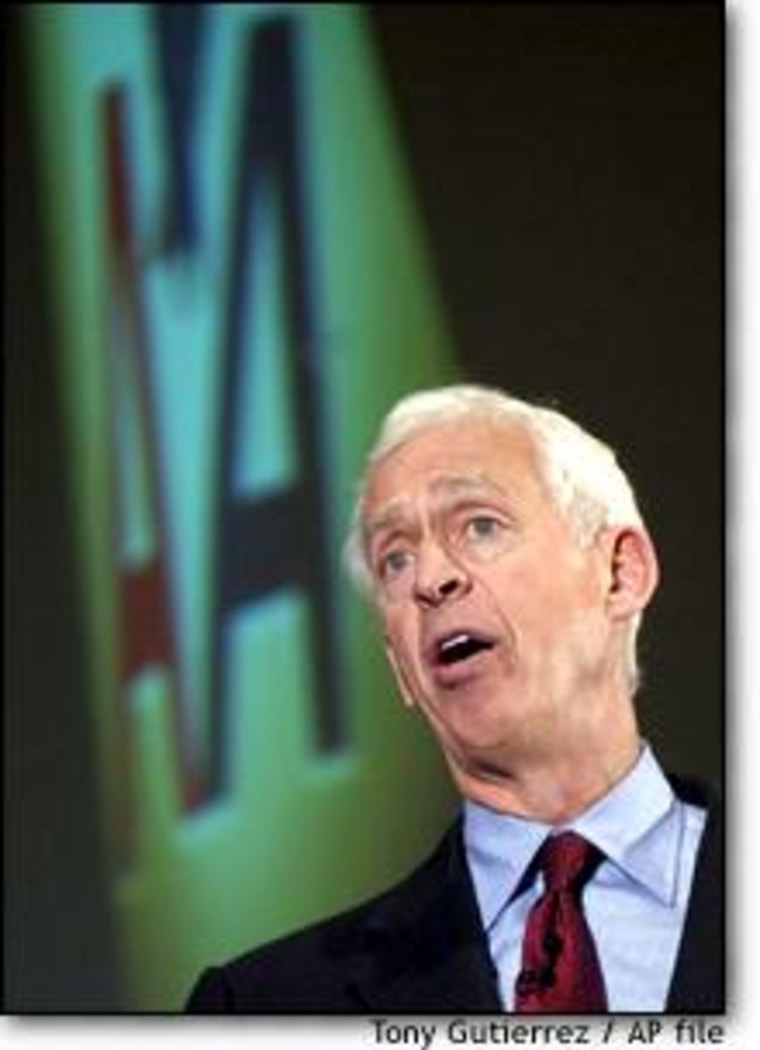

The trust covers the pension packages of American Airlines’s parent AMR Corp. Chairman and CEO Donald Carty and 44 of his top executives.

It was disclosed in an attachment to the company’s annual report, filed Tuesday with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Some members of the airline’s unions were aware of the arrangement after it was filed Tuesday, and union representatives were apparently told of it during negotiations — though negotiators were required by American to sign confidentiality agreements and could not reveal certain details to rank-and-file union members.

The trust was created last October 14. In a prescient consideration of its current troubles, the document creating the fund — which was designed as an amendment to the airline’s executive pension program — specifically stated that it “shall not be subject to the claims of the creditors of the Corporation in a bankruptcy or other insolvency proceeding under Federal or state law.”

In specific, it allows a group of top named executives to have their pension contributions removed from the company’s assets and placed in the independent trust. The list includes Peter Bowler, president of American Eagle; Daniel Garton, executive vice president of marketing; general counsel Gary Kennedy; and most of AMR’s other vice presidents.

That money is considered direct income and is subject to federal taxes, but after it is transferred to the trust, it is no longer part of AMR’s assets and cannot be targeted by creditors if the airline were to go bankrupt. It is a legitimate retirement option under 402(b) and 404(a) of federal tax code, which also requires the company to deduct taxes from the retirement funds before it turns them over to the trust. Many companies adjust the gross value of the contribution to cover the required taxes.

The trust is governed by an executive committee, which includes Carty, American president Gerard Arpey, CFO Jeffrey Campbell and Susan Oliver, senior VP of human resources. All qualify for retirement benefits through the trust. The funds are managed by an independent trustee, in this case Wachovia Bank of Winston-Salem, N.C., which also manages the carrier’s executive pension program. Wachovia, consulting with the committee, can invest the cash as it sees fit so long as it adheres to some broad guidelines to “preserve principal and liquidity” and “maximize income.”

“These arrangements do not have a direct material financial impact for the airline,” said Philip Baggaley, airline analyst for Standard & Poor’s, “but to the extent that they complicate labor relations — or for that matter, requests for federal aid — potentially they can cause difficulties.”

Pension benefits at AMR vary, but a 20-year employee would receive about one-third of average earnings — including bonuses — upon retirement. Carty’s base salary in 2001 was $585,813, which was 33 percent less than a year earlier. He’s credited for over 29 years of service. He has been with the company since 1979, though he left for two years to work at Canadian Pacific Airlines. Based on that salary, according to American’s pension calculation table, he would currently get about $330,000 in pension benefits per year. However, that does not include any compensation for bonuses, which he has declined since 2001. Previously, he collected significant bonuses, including $1.35 million in 2000, which means his annual package could exceed $900,000 if he begins collecting bonuses again.

The executive pension fund, known as the Supplemental Executive Retirement Plan or SERP, is designed to cover executive pensions beyond the maximum pension amounts traditionally allowed by the IRS, currently somewhere around $200,000 per employee. It is also separate from American employees’ 401(k) plan, known as $uper $aver, which has net assets of nearly $3.9 billion.

AMR spokesman Bruce Hicks said the company currently funds about 60 percent of SERP pension liabilities, and unlike some executive pension plans, it does not include extra compensation to cover taxes or other fees executives may face.

“It’s real straightforward,” he said. “It’s very clean in comparison.”

The timing of the disclosure, and the timing of American’s entire annual report, came unusually late. AMR filed the report on Tuesday as the unions completed their voting. AMR filed its last two annual reports in mid-March 2001 and late February 2002. But on March 31 of this year, AMR requested an extension to file the annual report, saying that it was “in the process of negotiating and implementing a crucial cost reduction program” and needed extra time.

“In effect, American is saying they don’t give a s—t about anyone but these 44 people,” says compensation expert Graef “Bud” Crystal. “It’s the Marie Antoinette school of management.”

Crystal wrote in a March column for Bloomberg News that Delta CEO Leo Mullin put together a similar plan for himself and 33 top executives. Mullin’s share alone, Crystal estmated, was $8.2 million in 2002.

Mullin has been widely criticized in recent weeks for taking a healthy salary and bonuses even as his airline has been pleading for federal aid to help mend its bottom line. After his $700,000 salary and a $1.4 million bonus were revealed last month, Mullin agreed to forgo an expected $1 million bonus this year, along with stock options and some other perks.

Crystal contrasts Carty’s efforts to handle criticism of executive pay with those of former American former CEO Robert Crandall, who was feared throughout the industry for his relentless tactics. But when trying to win wage concessions, Crandall eschewed his own pay raises and bonuses.

By contrast, Crystal argues, American executives’ new trust plan is a sign that airline executives at the airlines have little commitment to personal sacrifice in order to cut costs. “They’re voting with their feet that this company won’t survive,” he says. “The rats are trying to save themselves while the ship’s going down. That’s what rats do.”