When Alan and Kristine Wolf lost Spot to lymphoma a year and a half ago, their lives were shattered. Spot — a sometimes contrary, but always lovable, blue Abyssinian cat — was like a child to them. But after 18 years together in a Manhattan apartment, fond memories and hundreds of cuddly snapshots just weren’t enough. The Wolfs wanted Spot — or at least part of his “life force” — to live on, so they turned to 21st century science for a solution. Now, they pay a monthly fee to bank Spot’s skin cells, and look forward to the day when they may stroke his clone.

The wolfs are not alone. Hundreds of families across the United States and abroad have decided that their Fidos, Rovers and Kittys are “clone worthy.” And a handful of businesses has sprung up in the past few years to accommodate their desires, providing gene-banking facilities for now, until dog and cat cloning becomes a viable commercial option, which many believe it will be within three years’ time.

With names like Genetic Savings and Clone, Lazaron and PerPETuate, some of these companies sound as if they sprang from the imagination of a comic book writer. But these are serious businesses, working in tandem with scientists and embryologists at the world’s preeminent research facilities and universities.

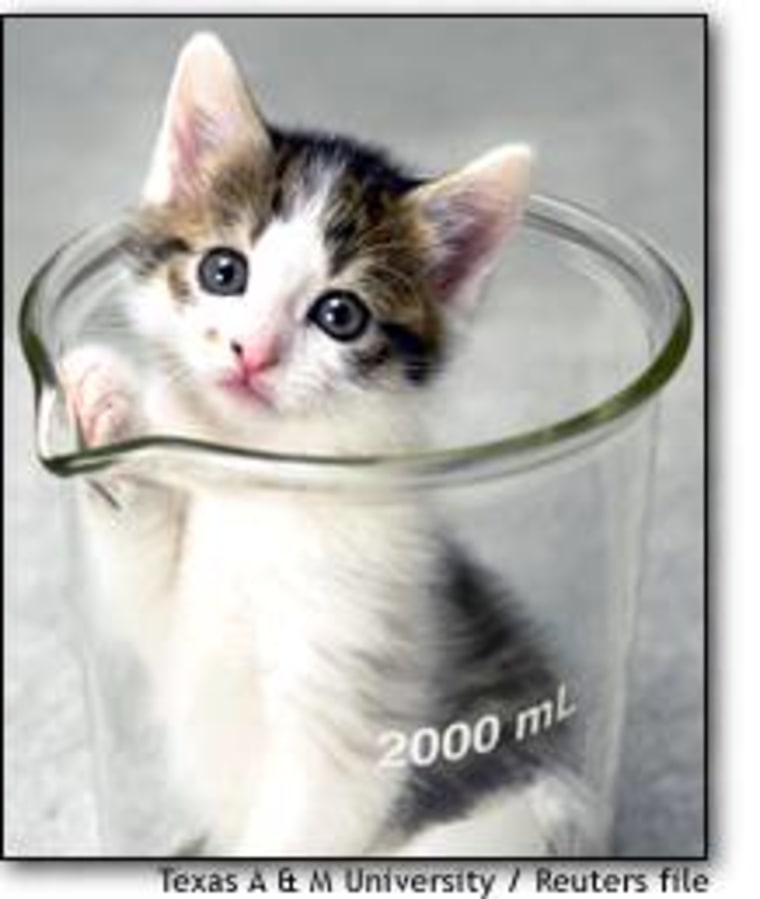

Just six months ago, Genetic Savings and Clone (GSC) made headlines when it announced the birth of CC — a fluffy, feisty, black-and-white tabby kitten, that just happened to be the world’s first cloned cat. CC, short for CopyCat, was born at Texas A&M University in College Station as part of the Missyplicity Project, a multi-million dollar dog cloning program funded by GSC. CC not only shows every sign of being a healthy and normal kitten, but she has also managed, in her so-far brief feline life, to provoke almost every human emotion — from awe, inspiration, and hope, to concern and even anger.

'Playing God' or solid science?

But while scientists, ethicists and animal rights groups duke it out, debating whether cloning animals like CC is right or wrong, safe or dangerous, akin to “playing God” or simply the healthy advancement of modern science, a growing number of people are thrilled with the news of CC’s “immaculate conception.”

For devastated pet owners like the Wolfs, CC’s birth means that Spot 2.0 may be one step closer on his journey back home, and for the pet cloning companies, it could mean big business is just around the corner.

“It’s what people want,” says GSC’s CEO Lou Hawthorne.

Asked about the viability of pet cloning as a business, he answers, “Nobody ever asks Jaguar why it’s important to make luxury cars. They make them because people want them. Millions of people think their dog or cat is unique. A business is based on demand and there’s a huge pent-up demand for this.”

Humane society speaks out

But public demand alone doesn’t make pet cloning acceptable to some organizations, most notably the Humane Society of the United States, which categorically condemns all commercial cloning of “companion animals.”

“Given the current pet overpopulation problem, which costs millions of animals their lives and millions in public tax dollars each year,” reads the society’s official statement on the subject, “The cloning of pets has no social value and in fact may lead to increased animal suffering.”

Hawthorne and other pet cloning advocates, however, say that on this one issue, the venerated animal-protection institution has got it all wrong. To back up his point, Hawthorne, a self-described “big supporter” of the Humane Society and its primary goal of curbing the stray animal population humanely, starts talking numbers. So far, as part of the research for the Missyplicity project, for instance, scientists at GSC have successfully spayed 10,000 dogs to obtain their embryos, according to the CEO. They also underwrite spay clinics for cats, research reproductive technologies for dogs and cats, and find hundreds of loving homes for retired animals after their “GSC association” is over, which is never longer than a year.

Code of bioethics

Hawthorne hastens to add that his company has also established its own contractually binding “code of bioethics.” This code, among other things, forbids the “transgenic” development of genetically modified organisms intended as either food or weapons (i.e., attack animals), and pledges to promote the psychological welfare of all animals under its care, conducting euthanasia only if an animal is suffering.

“We are ethical pragmatists,” explains Hawthorne, an animal lover himself, who grew up with “lots” of pets. “We came up with a code that works for us. Issues like ‘playing God’ are not as important compared with preventing the suffering of sentient beings.”

Pet owners who have already banked their favorite pooch’s cells seem to be ethical pragmatists too, eschewing any debate in order to focus on perpetuating their animal’s unique and loveable traits — even if it breaks the bank.

'Muted' sense of loss

The various cloning companies predict that early clones of companion animals will cost upwards of $20,000, and the cell preservation itself isn’t cheap. The initial tissue processing currently costs between $700 and $1,300, not including the $10 per month storage fee. But obtaining a small skin sample from the animal’s belly during a brief visit to the vet isn’t difficult. And once a living, sick, or even just-deceased animal’s tissue has been cryopreserved (frozen under specific conditions), the pet owners say that simply knowing they have options in the future gives them great peace of mind today.

“It has muted our sense of loss,” explains Wolf, reflecting on their decision to store Spot’s tissue with the Louisiana-based Lazaron BioTechnologies once they knew he was ill. Wolf, a physicist, adds that although he and his wife are in no way religious, they’ve discovered some kind of “religious” feeling in keeping Spot’s cells frozen — “a feeling that some aspect of his life force, even if not his consciousness, is still with us because these cells exist.”

The Wolfs say they’d want to clone Spot as soon as possible, but are willing to wait five or 10 years if that’s how much time it takes to iron out potential health-threatening glitches in the nascent cloning process.

Richard Denniston, co-founder and CEO of Lazaron, says most of his clients are like the Wolfs — highly educated professionals with a passion for their pets. “Because of the costs right now, there is certainly an economic segregation, so our clients are doctors, physicians, attorneys,” he explains. “They’re relatively successful and have also educated themselves about nuclear transfer (today’s method of cloning).”

Cloning caveats

Denniston and other pet cloning executives say they always present potential clients with several caveats. For instance, they remind them that the clone will not be the same pet, but rather a completely new animal with identical genes. It will definitely not have the same “memories,” and may not even have exactly the same temperament. Plus, if the original animal is spotted, as seen in the case of CC, who had a calico donor, but is not herself a calico, the clone’s coat pattern may not even be the same as the original pet’s.

The majority of pet owners eager to clone don’t seem concerned about such details, however. As long as the general look, build, and above all temperament are similar, they say, they’ll feel satisfied that some part of their beloved pet is “living on.”

In the Wolfs’ testimonial on Lazaron’s Web site, they write, “We hope to clone [Spot] in the near future, not to replace him, but to keep us close to his memory.” And Darrell and Kimberly Sadler of Stillwater, Okla., write of their little dog, Squirt, “Once in your lifetime, you have that special pet — the one you’d like to have forever. Although we know there will never be another one like him, it’s nice to know there’s hope for something as close as possible!”

The power of genetics

Ron Gillespie, founder of the Massachusetts-based pet cloning company PerPETuate, says these clients’ hopes are in no way misplaced. After years of research, including work on cloning the first calf back in 1997, Gillespie has become more and more convinced that genetics play a large role not only in build, but also in temperament and even coat pattern.

“If you have a mixed breed, you can get a near exact copy of that animal,” says Gillespie. “Physically, the spots may be in a slightly different place (due to environmental factors in the womb), but if the donor animal was 67 percent white and 33 percent black, the copy will have exactly the same proportions. We’ve seen this with cattle.”

But spots aside, “at the end of the day, it’s an exercise in hope,” concludes Gillespie. “If we give people hope and bring these animals back, I think it’s a pretty good thing.”

MSNBC.com’s Ursula Owre Masterson is based in New York City.