When New York state officials commissioned a high-tech environmental survey of the bottom of the Hudson River, no one expected to find what the scientists discovered: an archaeological treasure trove of hundreds of sunken ships. The survey should provide new insights into subjects ranging from Revolutionary War history to global climate change, researchers say.

The ships aren’t exactly treasure-laden galleons, but they’re valuable enough that the state wants to keep the precise coordinates of the wrecks secret. Among the suspected finds are Indian fishing weirs that could go back thousands of years, long-sought Revolutionary War ships and unusual sunken fortifications known as chevaux-de-frise, and 19th-century barges and sailing sloops that sank during the heyday of river trade.

The river survey could serve as a map to millennia of American history, hidden until now on the murky bottom of the Hudson. One of the key episodes of the Revolutionary War, involving George Washington and Benedict Arnold, focused on the fate of the Hudson and West Point.

“The Hudson River is probably one of the most historic waterways in the country,” said Charles Vandrei, historic preservation officer for the state Department of Environmental Conservation’s Bureau of Public Lands.

Treasures and troubles

All those artifacts came as a “big surprise” to the scientific team, said Robin Bell, a researcher at Columbia University’s Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory who played a leading role in the mapping project. The Department of Environment Conservation funded the bulk of the $3 million effort out of concern for the river’s health.

“The state wanted to know where the contaminated sediments were,” Bell said. “And the other question was, what are the different habitats?”

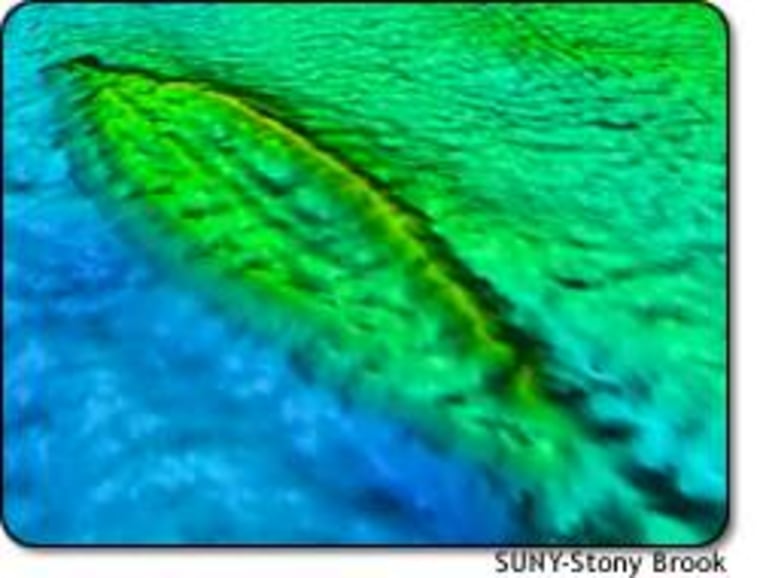

So, for more than four years, scientists probed the river bottom from boats on the surface, using a high-tech arsenal that included multibeam and side-scan sonar, ground-penetrating radar, acoustic “chirp” readings, sediment cores and sample grabs.

The mapping phase for the stretch of river from New York’s Verrazano Bridge to the upstate city of Troy was completed just a few weeks ago, Bell said. The resulting data show how the Hudson was carved over the centuries by natural phenomena and repeated dredging, the location of prized resources such as oyster beds, and other features yet to be interpreted.

But for now, the archaeological bounty looms as the most tantalizing prize — and the most difficult challenge. “Nobody expected this,” Bell said.

State officials are worried that if the precise locations of the shipwrecks were revealed, profit-seeking salvagers would flock to the Hudson River.

“With historical properties that are underwater, there’s a segment of the population that regards them as fair game,” Vandrei said. “There’s a little pirate in all of us, I guess, but the fact is that they’re owned by the people of the state of New York, and they should be treated as such.”

The rules are slightly different for military vessels, he said. They are still considered the property of the countries under which they sailed.

But the bottom line for the data relating to shipwrecks is that “it’s essentially against state law to publish those locations,” Vandrei said.

Scientific dilemma

He acknowledged that such a stand posed a big problem for the scientific team.

“It becomes a major issue of scientific integrity. ... You have the archaeologists arguing for one thing, and the biologists and the physicists making a good point that they have to publish the full data set,” he said.

For now, each data release is reviewed by the project team, with the state making the final decision on how specific the research can get. Vandrei noted that the data also have to be reviewed in light of the current war on terrorism.

“We’ve been very careful about not compromising things that we don’t want to compromise. ... One of the pieces of data that is being collected is things like submerged cables, submerged pipelines and bridge abutments, in fairly fine detail,” he said.

The concerns arise precisely because the maps are so detailed.

“It’s approaching photographic quality,” he said. “You’ve got a photographic image of whatever the equipment is looking at. That’s going to be an issue ... the ethical desire we all have a scientists to publish data as completely and accurately as possible so that our colleagues can look at what we’re doing, which is what science is all about.”

Bell said it could take several years to follow up on the data. Moreover, probing the bottom won’t be as easy for divers as it was for sound waves.

“Unlike in the Caribbean, where you can see things nice and clearly, in the Hudson you can’t see more than 2 feet,” she said. “Currents are fairly strong, and the visibility is fairly bad.”

The job might require underwater robots to blaze a trail for human divers, she said.

Other scientific payoffs

In the meantime, the researchers are pursuing other payoffs as well. Bell was intrigued by the distribution of fossil oyster shells in the bottom sediments. It turns out that there were optimal periods “where the Hudson has an environment in which the oysters thrive.”

Such periods occurred about 6,000 years ago and 2,000 years ago, according to an analysis of sediment cores.

“The same history you see in the river is recorded in Indian garbage piles,” Bell said. “It looks like those are climatically driven.”

Bell’s colleagues at Columbia believe that the oyster populations might have been affected by changes in sea level, or hurt by increased freezing and ice rafting during cooler times.

As scientists pore over the mapping data, they could well find new ways to preserve the Hudson’s resources in the future, in addition to unraveling its past, Bell said.

“What we are emerging with is a better understanding of how the river works,” she said. “For us, besides the historical artifacts, it’s understanding how the system works that fascinates us.”