Ten million acres of the Amazon rain forest have been charted in detail for the first time with the help of breechcloth-clad Indians toting GPS receivers, as part of an innovative effort to back up their land claims.

The mapping project, unveiled Thursday at the Brazilian Embassy in Washington, brought together four tribes of the northeast Amazon as well as the Brazilian government’s Indian agency, the nongovernmental PPTAL initiative to map indigenous lands and the Virginia-based Amazon Conservation Team.

The regions that were demarcated, the Tumucumaque Indigenous Park and the Rio Paru d’Este Indigenous Land, amount to a territory as big as the Netherlands. They’re just west of the world’s largest tropical park, and are occupied by the Apalia, Wayana, Tirio and Kaxuyana tribes.

Before the two-year project began, the only comprehensive maps of the Indian reserves were based on satellite and aerial photos, showing rivers and mountains but little else, said Vasco van Roosmalen, the Amazon Conservation Team’s Brazil program director and field director for the project.

“The Tumucumaque has 2,000 indigenous names that have never been recorded,” he told MSNBC.com.

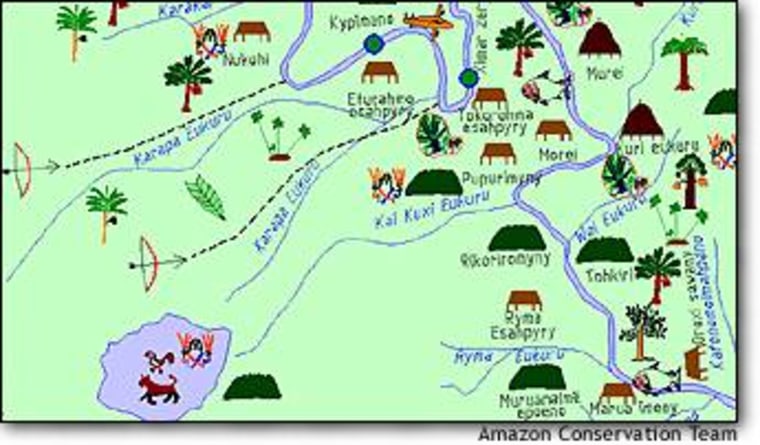

But the map, festooned with symbols to mark hunting trails and holy places, is more than just a curio.

“The white men have the Bible and other books to teach their kids about their ancestors. We now have our map to teach our children our history,” Apalai chief Joao Arana was quoted as saying in an Amazon Conservation Team report on the project.

The map also serves as an Amazonian zoning guide, indicating the location of villages, resources and even a strictly protected “no-hunting” zone in the middle of the tribes’ lands.

“Based on their map, the four tribes of this reservation will be able to better organize and develop their resources,” Rubens Antonio Barbosa, Brazil’s ambassador to the United States, said in a statement. “And they have prepared it wisely; the location of the widely coveted medicinal plants they know so much about — many of which have been illegally taken abroad from the Amazon rain forest — is not revealed in the map.”

Van Roosmalen said the map proves that the four tribes occupy the entire territory, which will help in the political fight against gold miners seeking to gain a foothold in Indian-controlled lands. It could also help build the case for economic development in the region.

“In terms of management and politics, the map is very important,” he said.

The map also served as an exercise in community-building. Before the project, the tribes tended to keep to themselves in separate territories within the Tumucumaque region. “When they came together to do this map, they saw that this was really one area,” van Roosmalen said.

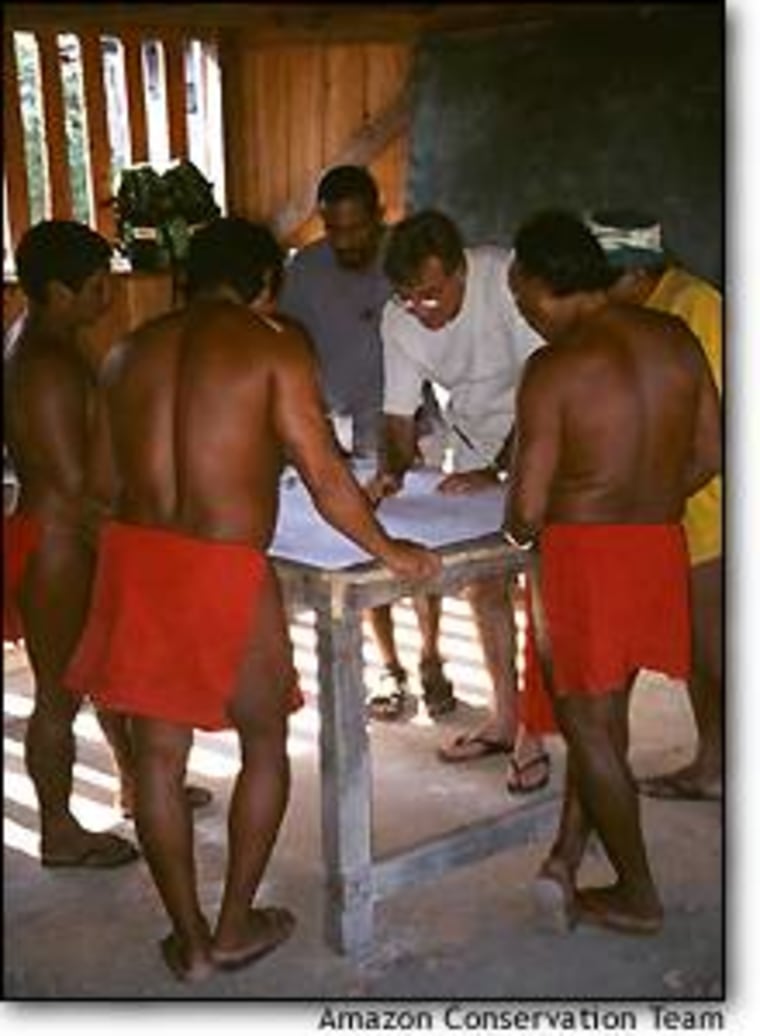

Cartographers trained the Indians to use the satellite-based Global Positioning System to match up landmarks with latitude and longitude, then gave them maps to fill in. Those maps were refined during two rounds of data-gathering over six months.

“The whole methodology is getting the knowledge that they have in their heads and getting that on paper,” van Roosmalen said. “They would go out into the villages with a blank, large sheet of paper ... then they would sit down with the elders, the hunters, the fishermen, filling in the legend and constructing the map.”

The resulting maps were digitally cross-checked with data from other tribes as well as satellite imagery and past mapmaking attempts. It was a “very inexpensive project,” costing less than $1 million, van Roosmalen said. Financial support was provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

The Tumucumaque project was inspired by a smaller-scale effort to map Tirio territory across the border in Suriname — and in turn, the Amazon Conservation Team hopes the latest results will set the stage for more ambitious plans to map 100 million acres of indigenous reserves in other parts of the Amazon.

Ethnobotanist Mark Plotkin, president of the Amazon Conservation Team, said such reserves are often the crown jewels of biodiversity in the Amazon. He noted that the Tumucumaque region harbors the headwaters of several major rivers that feed the Amazon.

“When the Indians say that the headwaters of a great river is sacred, and when the government of Brazil says they must protect their watersheds, they are essentially speaking the same language,” he said. “We all have a stake in perpetuating these resources. The map is a win-win situation for everyone concerned.”