Few prime-time TV shows would be willing to take on the bizarre realm of quantum mechanics and general relativity, string theory and 11-dimensional physics. But that’s just what “Nova” and physicist Brian Greene are doing for the miniseries based on Greene’s best-selling book, “The Elegant Universe.” Making the shows left Greene with a new appreciation of the bizarre realm of TV production — and a few bruised ribs as well.

Like the book, the TV version of “The Elegant Universe” starts with Einstein’s theories on how gravity works, shows how the weird world of quantum physics poses contradictions, and explains how string theory could resolve those contradictions.

The first two hourlong episodes premiere on most PBS stations Oct. 28, with the third episode airing Nov. 4. After it airs on TV, the whole shebang will be available for viewing online.

String theory — or, in its most recent incarnation, brane theory — isn’t exactly “Sesame Street.” The theories propose that the cosmos can be thought of as consisting of tiny strings or membranes that vibrate in 10 spatial dimensions. Some physicists have suggested that such theories and the mathematics behind them could provide the key to a “theory of everything” in contemporary physics, but the details are so dense they would try the patience of university students, let alone prime-time TV viewers.

“When someone brings up the idea of having three hours of string theory on TV, my first thought is, ‘This is going to be boring.’ But it’s not,” says Alan Ritsko, managing director of “Nova.”

Wizardry and charisma

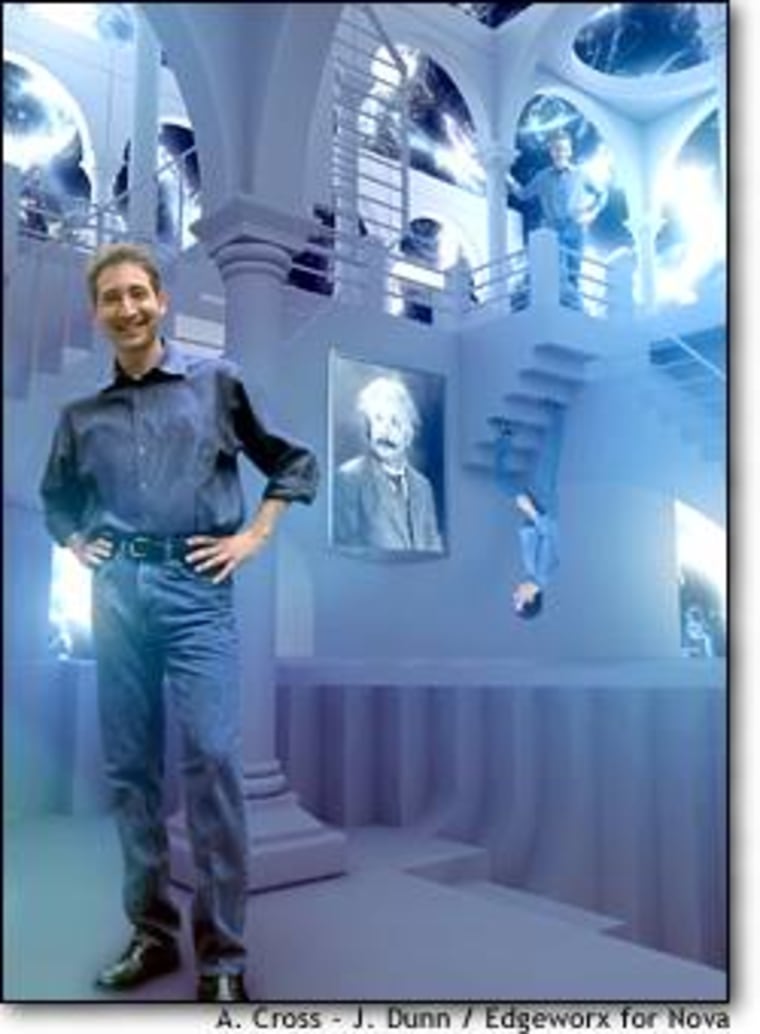

Fortunately for the producers, they have the wizardry of modern-day special effects as well as the charisma of one of physics’ rising stars on their side. Nevertheless, Greene, a physics professor at Columbia University, said it was a challenge to turn his book into a watchable TV show.

“That required a certain degree of simplifyng the science, but not as much as one would think,” he told MSNBC.com. “Since TV is so visual, so much can be communicated in one shot. One image can communicate what would require a couple of pages of text.”

For example, Greene and the producers drew upon special effects to show how the concept of strings could reconcile general relativity and quantum mechanics.

“We’re able to show the little strings down in the microscopic depths of the spatial fabric, in a sense spreading the fabric out .. and calming the jitters that space would otherwise be subject to,” he said.

The shows draw heavily on computer animation and green-screen virtual effects, with Greene’s image added to fanciful digital settings. During one segment, Greene takes viewers on a tour of a “Quantum Cafe” where the jittery quantum world is scaled up into a cocktail lounge. Walls shimmer, bar patrons fade in and out of existence, and multiple Greenes reach for a glass of orange juice that morphs from blue to red to green.

For Greene, doing the show was sometimes as disorienting as the quantum world.

“It’s hard, because you’re interacting with things that are not there,” he said. “I guess that’s what actors are good at and used to, but I’m no actor, so for me it definitely required a certain leap and a certain stretch of what I’m used to doing. But when I see it on the screen, it seems to work pretty well.”

Greene recalled one green-screen session in which he was being filmed leaping off a virtual building.

“I had to be strung up in a harness as a big fan was blowing my hair and jacket. ... I was quite afraid to be strung up at this height so I asked them to make the harness very tight,” he recalled. “They made it so tight that I couldn’t sleep on my right side for about six months.

“I think I must have broken a rib or bruised it quite strongly,” he said with a chuckle. “No hurdle too high if it’s going to aid in the communication of science.”

Sample the symphony of everything

Frontiers of physics

The TV series adds emphasis to some theories that have been fleshed out further since the book came out in 1999, Greene said. For example, more attention is devoted to “brane-world” theory: the idea that our three spatial dimensions might be a slice within a larger multidimensional space, and that parallel universes could be separated from ours by a mere fraction of a millimeter.

“I like to think about it using a ‘loaf of bread’ analogy,” he said. “It’s as if the entire universe is a giant loaf of bread, and the piece that we know about is but one slice in this larger loaf. ... In fact, we use that analogy in show three. We’re actually at a bakery. I’m slicing this loaf of bread, and we see these pieces of a universe that are glued to each of these slices of bread.”

Such flights of theory might lead practical types to ask: “Where’s the beef?” Where could scientists ever find the evidence to show whether one multidimensional theory or another actually reflects reality, and what impact can brane-world theory have on everyday-world physics?

That’s exactly what Greene is focusing on in his current work: “We’ve been working very hard to try to see whether string theory might leave some subtle imprint on some of thse cosmological observations that are being done now.”

He’s also looking for theoretical explanations for why we perceive only three spatial dimensions and have been missing out on perhaps six others. Any answers would likely spark a profound new understanding of how gravity works, he said.

Greene intends to delve more deeply into brane-world theory, as well as other theories about the nature of space and time, in a new book titled “Fabric of the Cosmos,” due for publication in February.

“It gets into questions like, why does time seem to flow? And why does it seem to flow only in one direction?” he said. “Are these real features of time, or are they imposed on time by human perception?”

For now, however, Greene has no plans to go back in time for a revision of his “Elegant Universe” book, although a new preface has been written to tie in with the TV series. Even four years after its publication, the book still largely represents the state of the art as a popular explanation of string theory, he said.

“For anybody who watches the TV show and says, ‘That’s interesting, I get the rough idea, but I really would like to understand it better’ — that person, I hope, would turn to the book, because there is a more leisurely discussion of most of the ideas in the book,” he said.