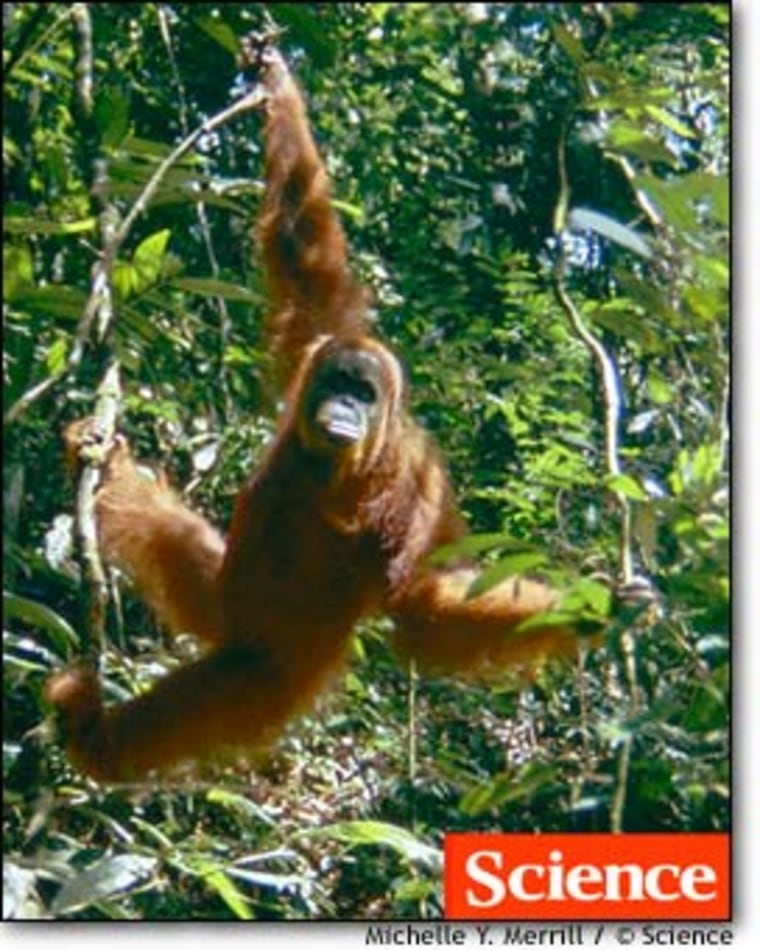

In the wild, groups of orangutans share distinct “tricks of the trade” for feeding, nesting and communicating, and scientists say these behaviors represent humanlike culture. The discovery offers tantalizing new clues about our own evolution, say the authors of a study in Friday’s issue of the journal Science, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

“Human culture didn’t come out of nothing,” said Duke University’s Carel van Schaik, lead author of the study. “It was built on a firm foundation. Early hominid material culture wasn’t that different from what we see in apes today.”

Van Schaik and his co-authors define culture as socially transmitted behaviors that vary from region to region. Such behaviors were discovered among wild chimpanzees — humanity’s closest living relatives — in the late 1990s.

Yet until this year, no one was on the lookout for cultural elements among our second-closest kin, the orangs, although there have been study sites in their remote Indonesian homeland for 30 years. So last February, with support from the Leakey Foundation — a group devoted to research on human origins — representatives from all six orangutan research sites gathered to sift through what van Schaik described as “a mountain of data.”

The experts shared observations and spent hours reviewing videotape of orang behavior. Together, they identified 24 cultural elements, each of which is common in at least one area and rare or absent in others.

These findings suggest that the evolutionary origins of primate culture could reach back beyond 7 million years ago, when the ancestors of chimps and humans diverged, to about 14 million years ago when orangs split off from this evolutionary branch.

Tools, nesting and the ‘Kiss-squeak'

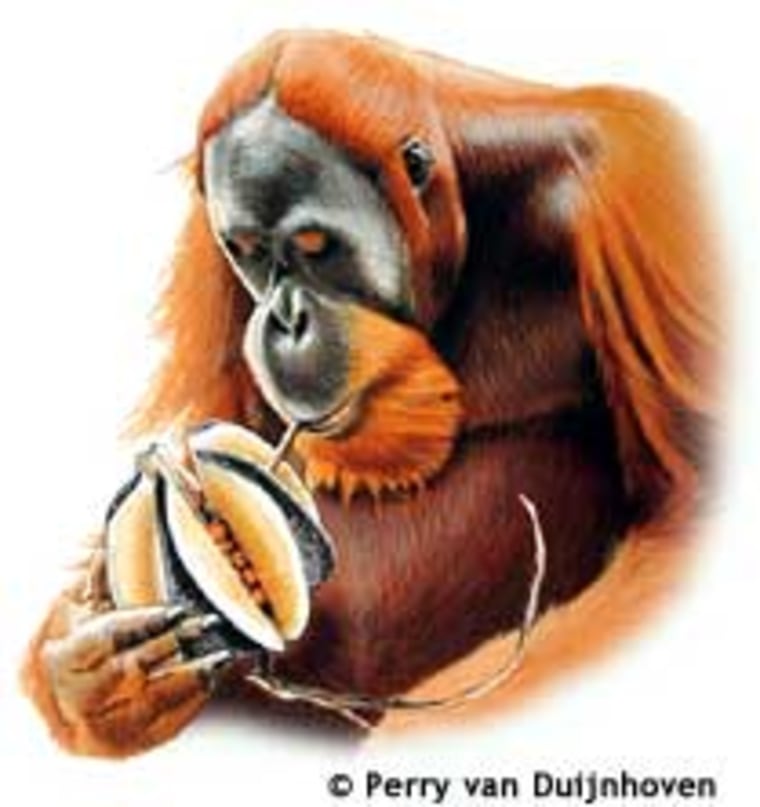

Many of the orang cultural behaviors involve feeding tools, such as using leaves to handle spiny fruits or a leafy branch to scoop water out of a knothole. Others revolve around nesting, such as building a cover to protect from rain or sun. Still others are ways of calling to one another, like the “kiss-squeak,” where orangs in some areas press their hands or leaves against their lips to make a loud sound.

Documenting these behaviors and their variability from place to place, though, was not enough to prove that they represent culture. The orang experts needed to show that these behaviors did not simply arise independently when apes faced similar ecological conditions.

The researchers found three lines of evidence to confirm that the behaviors are cultural and not ecological. First, sites that are closer geographically also have the most similarity in behaviors. This suggests that animals pass along their skills as they move from one area to the next.

Second, the number of cultural behaviors is highest in regions where apes spend more time near each other and thus have plentiful learning opportunities. Although orangs are “on the low end of the sociability scale” according to van Schaik, they tolerate one another when food is readily available. He described young orangs as “incredibly eager to study everybody they meet,” and recounted one incident where he watched a juvenile creep to within a foot of an older male to watch him sucking ants out of a hollow twig.

Finally, apes in similar habitats do not share more behaviors than those in different habitats. This points away from the simple explanation that when animals face the same challenges they develop the same solutions, a pattern van Schaik called “convergent innovation.”

Another example that supports a cultural explanation for the behaviors comes from one of van Schaik’s research sites on the island of Sumatra. Orangs on one side of a major river use sticks to extract seeds from a prickly fruit; their peers across the water don’t. If these behaviors were driven by habitat, this wouldn’t make sense, said van Schaik. “There are sticks and fruit on the other side of the river. What’s lacking is innovation,” he added.

They're not 'furry people'

Van Schaik is quick to note that his team is not arguing that orangs are “furry people.” Culture, he said, is “a very heterogeneous concept.” There are many kinds of culture, and species ranging from crows to dolphins may display different kinds in varying degrees. “What we can begin to do now is map the differences and learn what makes humans human.”

One key difference between human culture and all others is our heavy reliance on symbolism, where arbitrary meanings are attached to certain activities. Yet even here, the first stirrings of such behavior may exist among orangs. In two groups of the apes, it is common for individuals to blow a spluttering “raspberry” as they bed down for the night. Could it be that they are calling “good night” to one another?

Sadly, learning more about the fascinating orangutans is “a race against time,” according to van Schaik. A state of near-anarchy in Indonesia since the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998 has intensified poaching of orangs and logging of their forest homes, even in nominally protected areas.

The orang population has been devastated, crashing to half its former level in eight years, the time it takes for a female to bear and raise a single baby. Perhaps 20,000 animals remain.

Van Schaik does see some signs of improvement. The Indonesian press has begun to cover the crisis, and awareness of the problems is growing. Local authorities are taking notice, and a new protected area has been established on Borneo. The nation’s justice system is reorganizing, making it possible once again to enforce the laws.

Van Schaik praised the coalitions of local and foreign conservationists, who have struggled to rescue injured and orphaned orangs and to fight for their protection. “People who care make a difference,” he said with admiration.

The hints that the renewed conservation efforts may be successful come not a moment too soon. As van Schaik and his co-authors found, rich habitat with abundant food is critical for orangutans to gather closely enough for juveniles to learn the life skills developed by their elders. Without such skills, orangs could face even lower survival rates. Van Schaik has predicted that if conditions don’t improve, wild orangs will be extinct within 10 years.

If the worst happens and orangs disappear from their forest habitats, mused van Schaik, mankind might be able to save the species through captive breeding. “Genetically, we could reintroduce them in the wild, but their cultures would be gone forever,” he said.