Could America’s spy satellites and ground cameras have taken pictures of tile damage prior to space shuttle Columbia’s re-entry on Saturday, and would it have mattered? The answer is a qualified yes to the first question and almost certainly no to the second.

NASA admits it considered having the U.S. intelligence community take pictures of the orbiter’s left wing, but decided against the idea because it said the pictures have not been very useful in the past. Moreover, they were confident in their own technical analysis that the Columbia’s tiles had not been sufficiently damaged by a piece of insulation that struck the orbiter’s left wing at launch.

There have long been reports that both Keyhole spy satellites, operated by the supersecret National Reconnaissance Office in Virginia, and two sophisticated ground cameras in Florida and Hawaii, operated by the Air Force Space Command, have taken snapshots of the shuttle to help NASA assess safety concerns, primarily on Columbia’s first mission in 1981, when tile damage was a major concern.

Yesterday, Ron Dittemore, the director of the shuttle program, talked elliptically of “other assets” that could be used to help determine damage.

“Recall a year or two ago, we lost the drag chute door. Right at liftoff, it fell off. And we actually tried to take some pictures of the back end of the vehicle ... and those pictures that we received were not very useful to us,” said Dittemore in a NASA press conference Saturday. But in this case, he continued, “We couldn’t do anything about it anyway. We were in the best possible position, and so we elected not to take any pictures from any other sources, and that’s the way it played out.”

A senior U.S. intelligence official would not directly confirm that America’s spy satellites are used to image the shuttle, but left little doubt they have been used.

“I can’t talk about spy satellite capabilities,” said the official. “But I saw the NASA press conference where they said they could have used other assets to image the tiles ... and I will let you draw your own conclusions.”

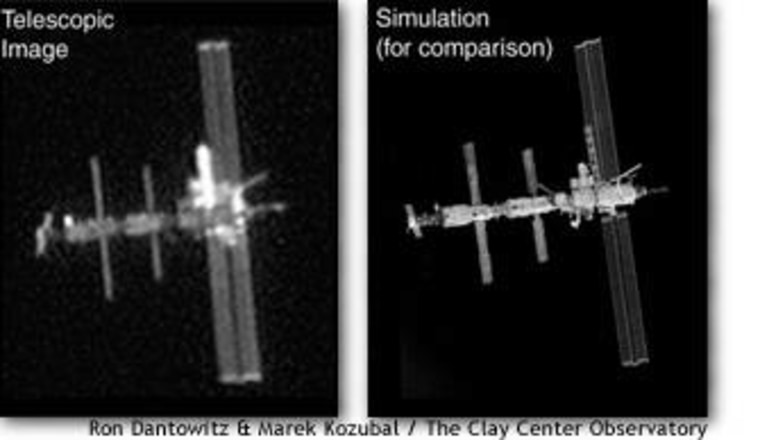

Images of Columbia

Ted Molczan of Toronto regularly monitors the activity of U.S. spy satellites. While current orbital data for the KH-11 spy satellites is classified, he said, the data was unclassified in April 1981 during the shuttle Columbia’s first flight and it indicates that the two spacecraft came close enough for the KH-11 to image the shuttle. “There were no close encounters on April 12,” said Molczan, talking about the first day of the shuttle flight, “but there were several fairly close ones on Apr 13.”

During that closest encounter, Molczan said, the shuttle was sunlit and the two were only about 70 miles apart at a slant angle, presumably good enough for taking a good picture.

Still, the thick veil of secrecy surrounding much of the spy satellite program makes it difficult to determine just how good the imagery would be.

Keyhole-class satellites are reputed to be able to see objects as small as 4 inches at a distance of 180 miles, Molczan said, and at a range of 70 miles, resolution would improve to about 1.5 inches.

But Molczan warned that the satellite’s angular velocity — the rate at which it turns to maintain a path along its orbit — might have blurred the image. He also questioned whether the contrast between the shuttle tiles and the surface to which they are bonded would have hindered image quality.

“If ... image quality was likely to have been poor, then I suppose it made sense not to request them,” Molczan noted. “On the other hand, it might be argued that if a sufficiently large defect existed on the shuttle, even a low-res image might have been worthwhile, if only to aid in diagnosis.”

Intelligence historian Jeffrey T. Richelson, author of “America’s Secret Eyes in Space”, said the Columbia was not the first spacecraft to be imaged by a spy satellite. In 1979, as Skylab was beginning its fiery if controlled descent to Earth, it was being watched by the KH-8 “Gambit” satellite.

Moreover, space historian William E. Burrows, in his book “Deep Black” reported that two ground imagery stations — “Teal Amber” in Malabar, Fla., and “Teal Blue” atop Mt. Haleakala in Hawaii — did take snapshots of the Columbia on that first mission. The cameras have long imaged satellites and orbital debris using sophisticated laser and electro-optical devices.

“Teal Amber and Teal Blue are so good they were used to scan the Columbia on her maiden flight in April 1981 in an effort to determine the extent of tile damage,” Burrows said.

What to do?

Even with those images, NASA officials maintained, little — if anything — could have been done to repair any damage.

“Once you get to orbit, you’re there, and you have your tile insulation,” Dittemore said, “that’s all you have for protection on the way home.”

Nor would it have been feasible, NASA maintains, to use the International Space Station as a backup destination for safety.

One NASA official said Columbia could not have docked with the space station: Columbia did not have the necessary docking mechanism on board this flight since the mission did not involve a visit to the station. The docking mechanism is a module that is only used when the mission involves docking with the space station.

Robert Windrem is senior investigative producer for NBC Nightly News. Tierney O’Dea, an associate producer for Nightly News, has written extensively on NASA and the shuttle program.