Just two years ago, the Russian space program looked as if it was headed for the dustbin of history, due to falling budgets and a falling Mir space station. Today, with America’s space shuttle fleet grounded, the full weight of human space flight rests on Moscow’s shoulders and the turnabout could change the shape of the final frontier.

Even as NASA investigates Saturday’s breakup of the shuttle Columbia and the death of the seven astronauts aboard, three other space voyagers are still living and working on the international space station, dependent on Russian transport technology.

For now, a Russian-built emergency capsule is their only way back to Earth. They’re dependent on food, water and supplies delivered by Russian cargo ships like the one that arrived just Tuesday. And if three fresh astronauts arrive to replace them, they’ll arrive on a Russian orbital taxi.

“It is fascinating watching the American political community come to understand how fragile is the NASA infrastructure in the best of times, and how dependent is the United States on Russia for continued operations in the best of times,” MirCorp President Jeff Manber said in an e-mail from Moscow, where he met with Russian space industry executives.

Over the past few years, Manber has seen the other side of the coin as well: For years he tried to keep Mir afloat as a commercial venture, beating the bushes unsuccessfully for Western investment. His experience points to the key dependence that the Russian space effort has on the United States and other partners in the 16-nation space station project.

“The Russians need income,” Manber acknowledged. “They need resources.”

Russian space officials also admitted as much this week, even as they expressed their sympathy over Columbia’s loss and insisted they had the technical capability to keep the station going.

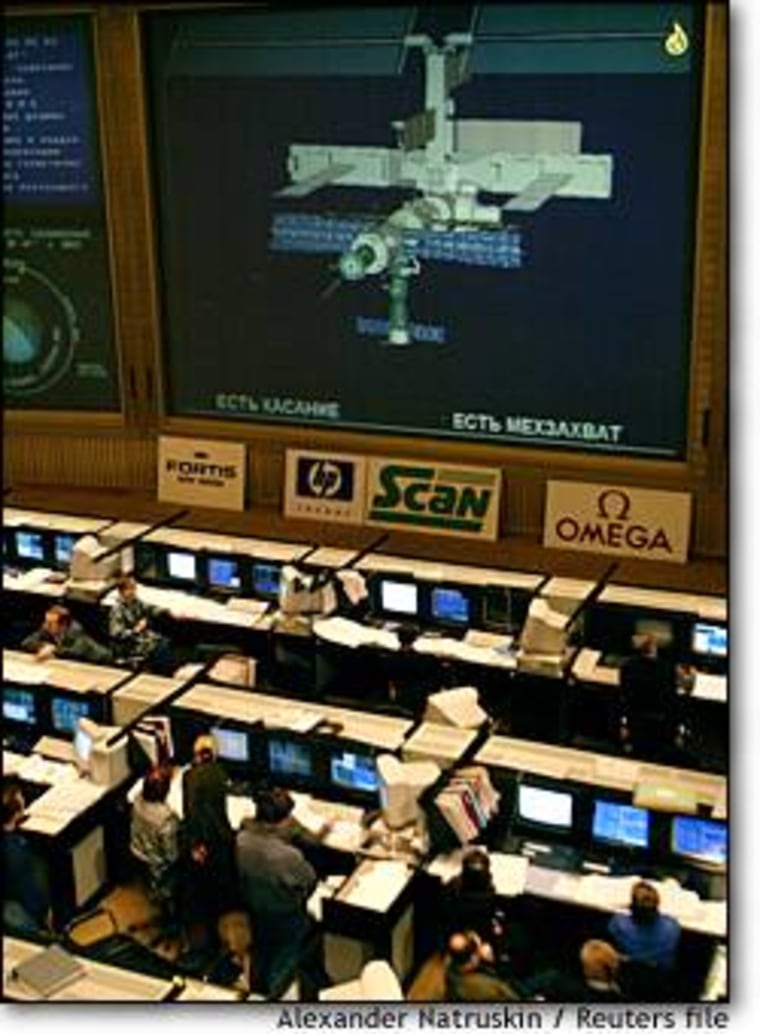

“We will need money for that,” Yuri Semyonov, chief of the Russian rocket firm Energia, told reporters at Russian Mission Control outside Moscow. “If we get the money, we will mobilize all our resources and provide the spacecraft.”

If the shuttle fleet is grounded for two years — as was the case after the 1986 Challenger explosion — tens of millions of dollars would have to flow from NASA to Energia and other Russian firms to sustain a space station that cost tens of billions of dollars to build.

For now, that’s a big “if,” said Marcia Clark, a space policy expert at the Congressional Research Service in Washington.

“The key to all of this is whether it’s a six-month problem or a 36-month problem or a 60-month problem,” Clark told MSNBC.com.

If the space shuttles can return to service by summer, there would probably be little long-term impact on station operations, said Gen. Michael Kostelnik, NASA’s deputy associate administrator for space flight. “All the things we need are in good shape through June,” he told reporters.

Best-case scenario

Even in that best-case scenario, there would be an impact: The current crew had been due to return on a March shuttle flight, but now the most likely plan calls for them to be replaced in April by a caretaker crew flying aboard a Russian Soyuz craft.

The April-May flight was supposed to be a “taxi mission,” bringing up short-term visitors only for the purposes of exchanging the old Soyuz emergency capsule for a new one. It used to be the favored flight for millionaire passengers such as Dennis Tito and Mark Shuttleworth. As of this week, the ticket window for space tourists is closed.

Under the new mission plan, the Soyuz exchange provides the only opportunity to switch crews. The current Expedition 6 crew would fly the old Soyuz back down to Earth, making room for Expedition 7.

For NASA, there’s no extra cost. But the arrangement is a money-loser for the cash-strapped Russians, since they won’t get the $10 million-plus that they collect from each European astronaut or millionaire tourist for a 10-day trip to the station. Each Soyuz flight costs the Russians more than $20 million — small change compared with the estimated $500 million cost of a shuttle flight, but a fortune for Moscow.

Worse-case scenario

If the shuttle moratorium goes much beyond June, the Russians might have to play a significantly expanded and more expensive role in the space station. Russia agreed to provide two Soyuz crew capsules and three Progress cargo ships annually. But that level of support assumed that space shuttles would be able to deliver tons of water and supplies during their visits. The water supply could become particularly crucial, since NASA’s system for reclaiming drinkable water from the station’s air is currently on the blink.

Still more Progress ships would be needed to fill the supply gap. “The crunch may come with the cargo part of it in the near term,” Smith said.

But the Russian space industry’s production pipeline has been withering away due to money problems, and it would take millions of dollars to speed up operations at Energia and other Russian space contractors. Even then, there are limits: Currently it takes between 18 months and two years to build a Soyuz or Progress.

“You can’t get a woman to have a baby in one month,” NBC space analyst James Oberg observed.

The Progress ships and visiting shuttles also provide periodic lifts or “reboosts” to the station, compensating for the slight atmospheric drag that tends to bring down orbiting spacecraft. “Over the next calendar year, we are OK with our boosting plan,” NASA’s Kostelnik said.

But beyond that, Oberg said, “There are not enough (Progress) vehicles in the pipeline to get enough fuel for long-term orbital maintenance.”

Legal problems

If the shuttle crisis drags on, the Russians’ extra charges for keeping the station going could rise beyond the $100 million mark. One option might involve completing construction of a cargo module known as the FGB-2, a spare copy of the station’s Zarya module. Both the original and the copy were built by Russia’s Khrunichev Space Center and the Boeing Co.

“That vehicle is 70 percent complete, and it could provide us with more than enough fuel to be pumped on board,” said Charles Vick, an independent space policy consultant. “It can have attitude control and enough supplies for a year.”

Oberg called the FGB-2 a “dark-horse savior” for the station’s long-term uncertainties.

But that option could only work if NASA provides the money. Under the Iran Nonproliferation Act of 2000, NASA is prohibited from paying the Russians for anything — even for extra Progress vehicles. President Bush would either have to certify that Russia was no longer providing missile technology to Iran or grant NASA a waiver because of a threat to the station’s safe operation.

Vick said the provisions of the act might also be circumvented if NASA arranged direct deals with Russian contractors, or U.S. middlemen such as Boeing. In any case, months of lead time would be required to have backup spacecraft ready in time, he said.

“If we get Congress to move its butt, which we’ve got to do now, we can pay for these things and get moving,” Vick said.

Another option is for the crew members to abandon the station temporarily, greatly reducing the need for power and supplies. “It is not the preferred option, but if it became necessary we could do that,” Kostelnik said.

The Russians are far less confident about leaving the station empty.

“The station’s parameters are such that it’s impossible to leave it without a crew,” Russian cosmonaut Pavel Vinogradov told The Associated Press this week.

Oberg is worried that unpalatable long-term options for the space station could lead NASA officials to put the space shuttles back into service sooner than they should.

“It’s a literal cliffhanger,” he said. “There’s going to be real psychological pressure to resume shuttle flights.”

Russian profile rising

Even if the interruption in shuttle flights turns out to be just a couple of months, Manber said the Russians’ profile in future space station operations will likely rise. “There had been a tendency before this tragedy to regard the international space station as NASA-driven,” he noted. That’s less likely to be the case going forward.

Russian space companies are already talking about a revival: This week, the firm that built the Soviet space shuttle — known as Buran, or Snowstorm — talked about resurrecting the project 15 years after it was mothballed. The Russian Aviation and Space Agency quickly shot down the idea, saying that the technical infrastructure for rebuilding Buran no longer existed.

“A spaceship is not meant to serve for centuries,” space chief Yuri Koptev told Russia’s Interfax news agency. “If a project evolves and functions, then it is alive. If it stops, it dies.”

Manber said he hoped the Columbia disaster would lead to a born-again vision of space flight, in which robotic ships rather than crewed vessels take over more of the grunt labor of building and supplying things in space. That would provide more of a role for the Russians, the Europeans and private contractors — and less of a direct role for NASA.

“The question now becomes what will be the best relationship in the future between NASA and the Russians, and the best use of the space shuttle,” he said. “I happen to believe personally that the shuttle should not be used for cargo — life is too sacred for that.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.