Spending weeks in isolation with your crewmates as part of a simulated mission to Mars may sound like the concept for a frivolous reality-TV show, but one of the commanders of an Arctic Mars simulation says it’s serious scientific business.

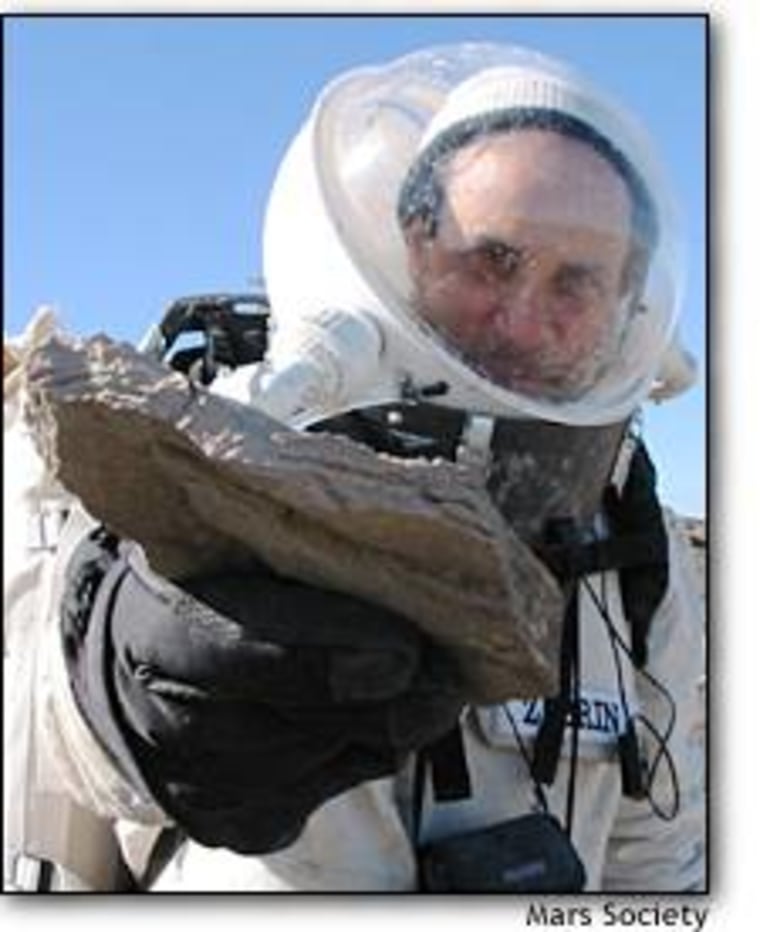

Robert Zubrin, a rocket scientist and president of the nonprofit Mars Society, spent three weeks on Devon Island in the Canadian Arctic in July 2001 — serving as commander for the society’s simulated Mars mission during much of that time.

Researchers from NASA and other institutions have been journeying to the island’s 12-mile-wide Haughton Crater each summer since 1997 because they consider the cold, dry, austere surroundings to be one of the places on Earth most like Mars. But in the summer of 2000, Zubrin and his colleagues took the exercise to new heights by erecting a privately funded habitat designed to reflect the likely layout for humanity’s first home on another planet.

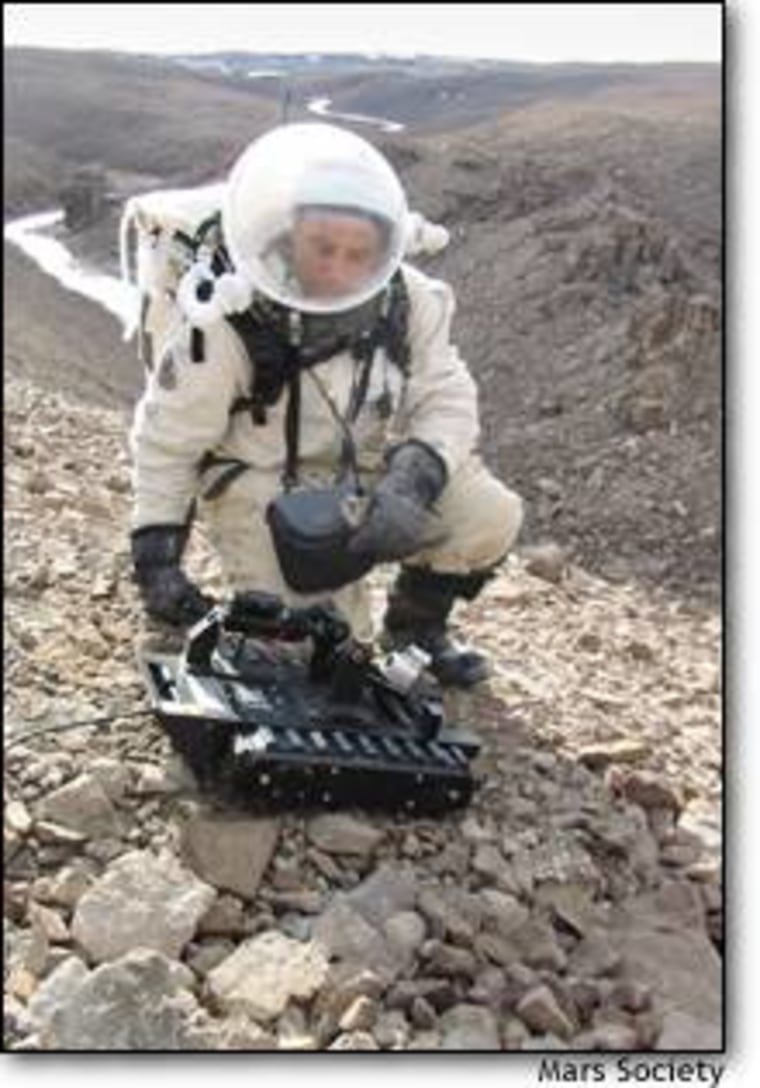

In 2001, volunteer crews of researchers started what the Mars Society expects will be an increasingly realistic series of simulations: Communications between the crews in the habitat and mission managers in California are delayed by 10 minutes or more to simulate the time it would take for signals to travel between Earth and Mars. Whenever crew members head out for simulated extravehicular activity, they don suits, helmets and backpacks with communication gear — and spend time in a fake airlock to duplicate the routines a Mars crew would have to go through.

Serious science

The airlock and the spacesuits may be make-believe, but the lessons are real, says Zubrin.

“It’s a very serious scientific endeavor,” he insists. “We were able to demonstrate a style of Mars exploration that exceeds what NASA’s current robotic program can do by several orders of magnitude.”

The crews set up networks of sensors that mapped the subsurface composition of the soil in several locations, surveyed the gullies and cliffs surrounding their two-story habitat, and cataloged ancient fossils as well as microbes clinging to life in the extreme environment of the Arctic. Such tasks that will be essential for determining whether life ever existed on Mars — and they are far beyond the capabilities of the most advanced robots, Zubrin says.

Zubrin says it “would take centuries before robots would be able to do anything like it.”

To be sure, the Devon researchers tested several robotic breeds, including miniature “telerobots” that could be carried into the field, then lowered down a cliff, sent into a crevice or rolled beneath a habitat to do reconnaissance. But Zubrin puts more emphasis on the human side of the equation: how explorers can live and work together, coping with the hardships and isolation of an extreme environment.

No back-stabbing allowed

The exercise has been compared to reality-TV shows like “Survivor” and “Big Brother.” Zubrin, however, says the reality of life in the Arctic — or, someday, on Mars — is “completely different” from the game-playing and back-stabbing as seen on TV.

“The last thing you want are competitive attitudes among the crew members toward each other,” he says.

Competition among prospective teams of Mars astronauts could play a role in the selection process, Zubrin said. And good-natured competition could put some zest into everyday tasks like cooking. “But you certainly don’t want to have one crew member trying to upstage another at anything serious,” he said.

Despite the best intentions, competition among scientists is unavoidable — on Mars or in the Arctic — when it comes to setting priorities for mission activities. Even in this case, voting someone off the island isn’t an option. Instead, Zubrin says, it will be up to a strong commander to control the mission agenda.

“It was an advantage for me as a crew commander not to have a particular personal investigative program of my own,” Zubrin said. “I think that should be the case for whoever is in command of a Mars mission — that they should be one step removed. I think it’s an advantage in perspective, because I do think there were instances where scientists were overfocused.”

Speaking of focus, what about the potential for sexual tension? A Mars mission would put males and females in close quarters for months at a time, but Zubrin brushes aside any suggestions that the mission could turn into an outer-space version of “Love Cruise” or “Temptation Island.” Instead, he draws a parallel to ships at sea.

“There have been women in every ship to date, and people just relate to each other as professionals,” he said. “I really think the question is overdrawn. ... It’s possible that some relationships might develop, but if they do, they would just develop in a natural way.”

Who's in control?

The Devon experience demonstrated that the old concept of “Mission Control” will have to give way to to something different on Mars, Zubrin says.

“You can’t ‘control’ a Mars mission from Earth. The Mars mission is going to have to be controlled by the people on Mars. ... There is just too much involved that is out of sight of Earth,” he said.

Zubrin prefers the term “Mission Support” — a unit that can provide logistical and psychological support but recognizes that it can’t call the shots.

The lessons learned in the Arctic are still being applied there, with simulations continuing under the command of Pascal Lee, a researcher for NASA’s Ames Research Center and the SETI Institute who pioneered the first Devon Island forays. When will all this make-believe give birth to the reality? NASA’s game plan for Mars exploration calls for sending a succession of robotic rovers and orbiters, then bringing samples from Mars back to Earth for examination, and then thinking about sending humans, perhaps around 2020 or later.

“I don’t think there’s any validity in that model,” Zubrin says. Orbiters would be useful for taking high-resolution pictures of potential landing sites or providing over-the-horizon communications, and landers could serve as trailblazers as well as beacons for manned spacecraft — but Zubrin sees little benefit in wide-ranging rovers or sample return vehicles.

“If we committed now, we could have people on Mars in 2008,” he says.

But what would it take for governments or corporations to commit the tens of billions of dollars required for such a mission? A race merely for TV ratings isn’t enough, and the kind of Cold War hysteria that fueled the race to the moon in the 1960s no longer exists.

“I don’t think we should have to do a Mars mission on the basis of hysteria,” Zubrin says. “I think we should do a Mars mission on the basis of a deliberate judgment that what we want to do is open up a new planet for humanity ... that we are continuing to be a nation of pioneers.”