Forty years ago, Sputnik and the Soviets set the course for a space race with the West. Now the satellite, the space race - and even the Soviet Union itself - are gone. But Sputnik’s legacy endures.

THE IDEA of sending payloads into space dates back to Nazi Germany’s wartime rocket program. But the space race began in earnest during the 1950s, when a group of scientists set a goal of putting a satellite into space as part of its agenda for the 1957-58 International Geophysical Year.

The United States set out in 1955 to meet that goal using Navy research missiles, in an effort known as Project Vanguard. Meanwhile, Soviet researchers led by aviation designer Sergei Korolyov moved ahead with their own project, using a much more powerful ballistic missile.

On Oct. 4, 1957, the Space Age officially began when the Soviets lofted a 183-pound shiny sphere from their Baikonur cosmodrome in Central Asia. Sputnik, which took its name from the Russian word for “fellow traveler,” went into a 98-minute orbit around Earth — and the Soviets exulted in their success.

The satellite’s prime payload was a radio transmitter sending out a harmless “beep-beep-beep” signal merely to declare its existence. Nevertheless, Sputnik struck fear into the hearts of Cold War Americans, who realized that the Soviets could just as well have lofted a nuclear-tipped missile to North America.

“That event was really a catalyzing event for the American consciousness,” says Bill Colglazier, executive officer of the National Academy of Sciences.

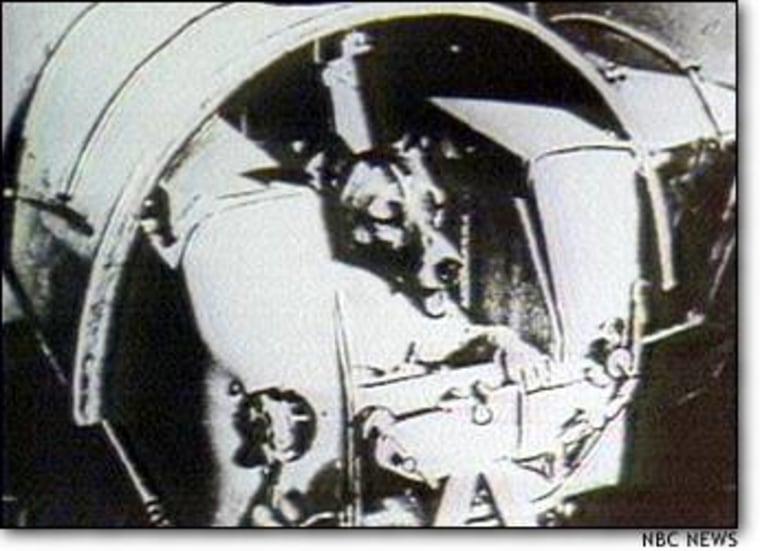

Washington’s embarrassment only deepened in the weeks that followed: In November, Sputnik 2 carried a dog named Laika into space (monitoring equipment indicated that the animal lived until the satellite’s air supply gave out).

And in December, America’s first Vanguard launch ended in fiery failure, earning the nicknames “Kaputnik” and “Stayputnik.”

President Dwight Eisenhower downplayed the imminent threat, but at the same time took steps to close what his critics called the “missile gap.”

In addition to Project Vanguard, a parallel effort known as Project Orbiter was lifted out of years of limbo: A team led by German émigré Wernher von Braun used the Redstone rocket as the foundation for a four-stage launch vehicle topped by a satellite. In January 1958, the United States sent the 31-pound Explorer 1 into space, and a sensor carried aboard Explorer opened the way for the discovery of the Van Allen radiation belts.

Later that year, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration was created to coordinate America’s space efforts. The Space Race truly became a two-sided contest — and the rest is history.

Scientists and military experts say Sputnik was a wakeup call, focusing attention on America’s technological gaps in 1957. But Sputnik’s echoes reverberate even in 1997, striking three chords in particular:

FROM RIVALS TO PARTNERS

Among the Soviets who exulted in Sputnik’s success was Valery Ryumin, who was at the time an 18-year-old laborer at the factory that built the satellite.

“It was a time of extreme excitement,” Ryumin recalls. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev visited the plant to congratulate the workers — and pass out goodies. “Back in those days it was very habitual,” Ryumin says.

Since then, spacefaring fortunes have changed radically.

In 1957, Moscow seemed invincible in space. But by the time Ryumin himself became a cosmonaut in 1973, America had won the Space Race decisively, sending seven missions to the moon while the Soviet moon program faltered. And now some in the West question whether Moscow can even run a competent space program.

Ryumin, who now serves as the Russian head of the shuttle-Mir cooperative program, says the days of competition in space are finished. “I’m sincerely hoping that we are going to work together for years to come,” he told reporters at Cape Canaveral last week.

The way NASA sees it, the Russian and American space programs have come to complement each other: NASA has been focusing on reusable transports — the fleet of space shuttles and its yet-to-be-built successors — while Moscow has concentrated on a series of space stations and study of long-duration flight.

Now both sides, as well as the European Space Agency and Japan’s National Space Development Agency, have joined in a $40 billion effort to build an International Space Station by the year 2003. The master plan means that no one nation will be able to conduct a space program in isolation or in secret — not even the United States — unless there is a dramatic rise in space funding.

“Who would have thought 40 years ago that we’d be doing this together?” said Frank Culbertson, Ryumin’s NASA counterpart. “We are irretrievably bound together in space now, I believe, unless one partner lets the other down.”

FROM POLITICS TO ECONOMICS

The U.S. Space Command counts Sputnik as No. 1 in the list of almost 25,000 spaceborne objects it has monitored over the past four decades. Sputnik fell off the active list long ago, but there are 8,600 other human-made objects currently being tracked by the Colorado-based military command.

Just in the past year, there’s been a significant shift in the breakdown of those orbiting objects, says Maj. Steve Boylan, chief of media relations for the U.S. Space Command and NORAD.

“This is the first year that there are more commercial assets in space than military assets,” Boylan says.

The new prominence of commercial satellites is more than just quantitative. “Where it used to be that the military was the leader on research and development, now the commercial [sector] has the lead, and we are tagging onto them,” Boylan says. “We’re learning from what they’re doing.”

Boylan points out that Sputnik was a wakeup call for the commercial promise of space as well as the potential military threat.

The first commercially developed satellite, AT&T’s Telstar, was launched in 1962, five years after Sputnik — and almost immediately began relaying intercontinental television signals. Since then, billions of dollars worth of telecommunications satellites have filled the sky. And a new generation of low-orbit satellite networks, such as Iridium and Teledesic, promises to extend telephone and Internet service globally.

All that hardware in orbit has created an infrastructure essential to banking and finance, communications and weather forecasting — an infrastructure that has to be protected from intentional or accidental harm, Boylan says. And that is something that occupies more and more of the Space Command’s attention.

“You don’t have to do something in space to affect space assets,” he says. “You can take out a ground installation. … If you can jam that signal in between, you can do just as good a job as if you took tht satellite out of the sky.”

Thus, the U.S. military not only monitors orbiting objects, but also the nation-by-nation capability to disrupt the orbital infrastructure.

Another part of the Space Command’s mission has to do with traffic control: Ironically, the military command that once stood on guard against Soviet threats now advises Russian space officials, through NASA, to look out for wayward space junk. Just last month, it was the Space Command that monitored the breakup of NASA’s malfunctioning Lewis satellite.

The skies are so intensely watched that a modern-day Sputnik would be picked up almost instantly. “We try not to be surprised anymore,” Boylan says.

THE EDUCATIONAL RIGHT STUFF

One of the ironies of the Sputnik phenomenon is that America’s paranoia about its technological gap led to a “first renaissance” in science education, says Bill Colglazier of the National Academy of Sciences.

Fearing that America’s educational system was falling behind to the Soviets, educators and policy-makers put more emphasis on physics, mathematics and other sciences — leading to a technological flowering.

“There was a wave of innovation in the 1960s,” Colglazier says. “Unfortunately, after that period it fell somewhat in decline.”

Colglazier says “the concern now is a fear that science education is more memorization. … The scientific community would really like to have the emphasis put back on the process of inquiry.”

But he also sees signs on the horizon of “a renaissance like we had in the days after Sputnik.” This time, the driving force isn’t the paranoia provoked by beeps up above, but the rise of the global economy and the resulting concern over national competitiveness.

“With the globalization of the economy, scientists and engineers realize that improving science education has an impact on the lifestyle and well-being of the American public,” he says. “But scientists realize it goes beyond that — that it’s in the United States’ national interest to improve its science education.”

So does that mean a nasty Tech Race is in the offing? Colglazier doesn’t think so. The modern scientific ethic, he says, should value global cooperation and environmental sustainability as well as technological prowess.

“Ultimately,” Colglazier says, “that will end up in a more peaceful world.”