Hundreds of astronomers were watching the skies when NASA’s Lunar Prospector probe crashed on the moon early Saturday. They were hoping for a sign of water vapor when the 354-pound spacecraft smashed into a deep southern crater. But they saw nothing.

David Goldstein, a University of Texas scientist observing from the MacDonald Observatory in west Texas, said no dust cloud or other visible indication of impact was detected by telescopes focused on the lunar south pole. “We didn’t see any evidence of the impact,” said Goldstein. “We didn’t see any dust. It is a bit of a disappointment.”

Lunar Prospector’s final experiment was an iffy proposition — in fact, NASA estimates that the crash has only a 10 percent chance of turning up anything interesting. But it was also a low-cost proposition, since the 18-month, $63 million mission formally ended Saturday, and NASA had always intended to crash the 4-foot-long spacecraft on the moon anyway.

At least 21 heavy-duty observing instruments were watching Lunar Prospector’s 3,800-mph crash at 5:52 a.m. ET Saturday. Among the biggest guns: the orbiting Hubble Space Telescope, the Submillimeter Wave Astronomy Satellite and the Keck-1 telescope in Hawaii — the world’s biggest optical telescope. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of amateur astronomers also were setting their sights on the moon.

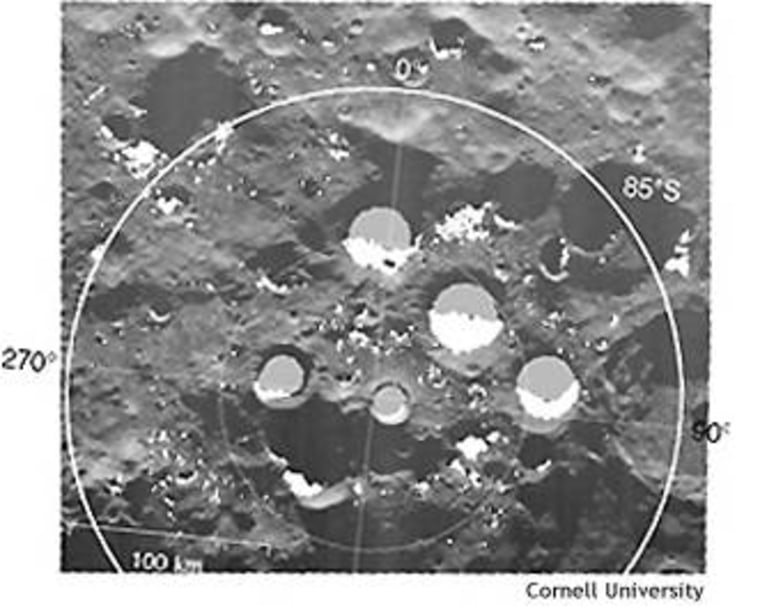

All these astronomers, looking in various wavelengths, had hoped to catch sight of debris thrown up from an as-yet-unnamed crater near the moon’s south pole. Scientists say that crater offered the best chance for detecting frozen water — and if the 354-pound spacecraft happened to hit a patch of ice just right, the impact could send several gallons’ worth of water vapor 15 miles or more above the lip of the crater.

“There were no visible plumes observable at any of the observatories across the country or around the world,” David Morse, a spokesman for Ames Research Center announced early Saturday. The absence of a plume actually confirms that Prospector hit its deep-crater target, Morse added. Another crash on another trajectory would have been picked up by the watching astronomers.

Hubble and other sensitive instruments just might be able to detect the ultraviolet signature of the water vapor as it breaks down into hydrogen and hydroxyl ions, something Morse said might take days or weeks to analyze. Should a hydroxyl plume be detected, it would provide further confirmation for a view that once seemed heretical: that the moon’s deep polar craters, permanently sheltered from the blazing sun, serve as reservoirs for billions of tons of ice collected from billions of years’ worth of comets striking the surface.

Scientists say such ice could be used by human settlers, not only for drinking water but also for nurturing crops and manufacturing rocket fuel.

Indications of polar water ice were picked up by the Pentagon’s Clementine probe in 1994 and by Lunar Prospector’s spectrometer last year. Last year’s measurements were based on indirect evidence: concentrations of hydrogen at the poles.

Iffy proposition

It was David Goldstein, a researcher at the University of Texas at Austin, who suggested that the long-planned crash have a scientific purpose as well.

“If we detect a signal, that is a slam-dunk,” Goldstein said. “If we don’t detect a signal, which is more likely in my opinion, it doesn’t say anything. Only a positive result has meaning.”

Last week, Stanford researchers Von Eshleman and George Parks cautioned that a positive result wouldn’t necessarily mean Lunar Prospector had hit ice as we know it. They said there was a possibility that the same sort of result could be produced by hitting mineral crystals with water molecules locked inside.

In response, Goldstein points out that it would take temperatures of up to 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit to liberate the water molecules. Lunar Prospector’s impact, however, should produce less than half that much of a rise in temperature, he says. Thus, Goldstein remains confident that if a positive result is produced, it will be an indicator of real water rather than hydrous minerals.

The amateur angle

Scientists will be searching through telescopic images pixel by pixel for the telltale signs of water, and Goldstein says there probably won’t be anything for backyard astronomers to see. Nevertheless, scores of amateurs were likely looking.

“There are plenty of folks who intended to watch, that’s for sure. The Internet is really alive with the subject,” said Bill Dembowski, president of the American Lunar Society and coordinator of lunar topographical studies for the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers. Both groups are geared toward amateur astronomers.

Because of the timing of the impact, Dembowski said the viewing prospects were much better in the western United States than in the East. He agreed that the chances of seeing anything weren’t high, but he also noted that amateurs are using increasingly sophisticated equipment, such as video-equipped telescopes that allow users to review an astronomical event frame by frame.

“If anybody in the amateur community sees anything, it will be somebody who’s video-equipped,” he said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.