There may be no “up” or “down” in the zero gravity of space, but when you pass the halfway point of a six-month space expedition, it sure ought to FEEL like downhill. And while the space station has been circling Earth sixteen times a day, the arduous psychological journey of its crew has passed a significant milestone. That was worth a party.

ASTRONAUT ED LU and cosmonaut Yuri Malenchenko took off from Earth on April 26 aboard a Soyuz spacecraft and began their “Expedition-7” sojourn aboard the International Space Station. By the time of their expected landing in late October on the rolling steppes of Central Asia, the two men will rack up about 190 days in space.

The longest previous U.S. two-man spaceflight was less than fourteen days, a Gemini flight almost forty years ago. Even for the Russians, who for 25 years have routinely made six-month orbital missions — even as long as 12 to 14 months — what makes this mission unusually challenging is that there are no visits by other manned space vehicles for the entire period. In the past 10 years, the Russians have mostly conducted three-person missions, often with visiting space shuttle missions both to Mir and the ISS. The psychological challenges of such missions are significantly easier.

Long two-man missions can be frightening to contemplate. Cosmonaut Valeriy Ryumin wrote in his space memoirs that on his way to the launch pad in 1978 for a six-month two-man mission, he worried about a short story he had once read by the U.S. author O. Henry. The tale dealt with the hazards of the western frontier.

“If you want to encourage the craft of murder,” Ryumin recalled reading, “all you have to do is lock two men for two months in an 18 x 35 foot room.”

Space psychologist Patricia Santy, formerly with NASA’s Mission Control in Houston, agreed the challenge is daunting.

“Obviously the two people involved must be very compatible to make it work,” she said. “In the case of a space mission, the two astronauts must be psychologically well-trained, as well as compatible.”

As for murder in space, Santy (author of “Choosing the Right Stuff”, the authoritative book on astronaut selection) was less dramatic but just as concerned:

“The training is especially useful so that you do not kill the other person when their personal quirks drive you nuts,” she said, “but it probably can’t help you from feeling like you’d like to kill the other person.”

“Good psychological support during the mission is crucial,” Santy said.

FOOD, MUSIC HELP STATION DUO NASA is playing close attention to the psychological issues of the current crew, mission manager Merri Sanchez told MSNBC.

“We’ve looked very closely at what we think the psychological impacts are and what we can do,” she said. “We make sure everybody is sensitive to the issue of mood cycles, and how to tell when they’re up and when they’re down.”

And the good results reflect this concern. “They’re over the midpoint but in very good spirits,” she said. “We had a little celebration for their first hundred days, a point that previous crews found significant.”

The party, at a local Houston restaurant, involved many of the control team along with the crew’s relatives and friends. “We brought in phone lines,” Sanchez explained, and Earth and space exchanged cheerful greetings and well-wishing. “Then we sent them lots of digital pictures,” she said.

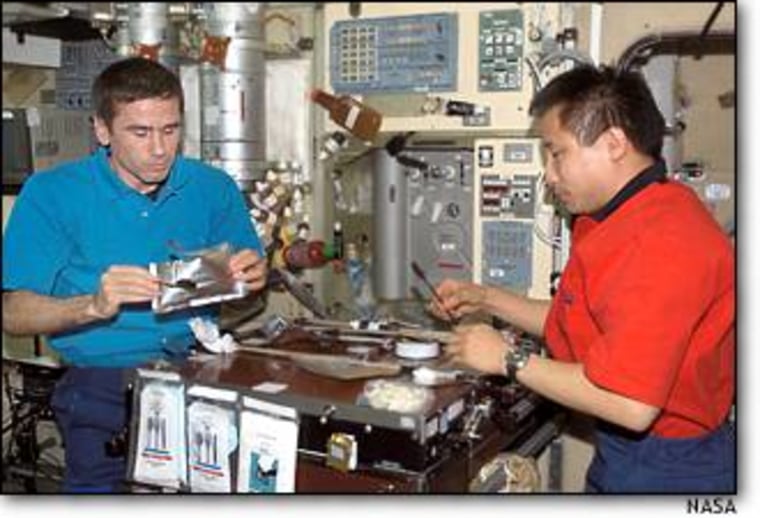

As with isolation experiences aboard submarines, at the South Pole, or on remote drilling rigs, another key to good morale is good food. And on this subject, the crew is apparently very happy.

“Ed enjoys the Russian food,” Sanchez said. “The crew is eating slightly more than other crews,” she continued, “and we think Ed is eating some of Yuri’s share too.”

And it’s not just the food shipped up for Expedition-7 they’re eating.

“We had some leftover odds and ends from Expedition-6, and a bit from Expedition-5,” Sanchez said, “and it gives them some variety.” On previous missions, some “expired” food packages were thrown out. “But not this crew”, Sanchez laughed.

Despite the high food input (and a “little bit less than planned” consumption of water), Sanchez said they were “very happy with the body mass.” This is measured by a Russian-made device that shakes the crewman’s body back and forth to determine his inertia.

Both men also spend up to three hours a day on the treadmill and other exercise devices. Added to that are regular housekeeping chores and about ten hours of productive work per day. That also leaves a few hours every day for leisure, another major reducer of stress.

InsertArt(1991672)“I spend this time working on some scientific experiments of my own,” Lu recently wrote, as well as answering e-mail and just looking out the window. “These hours go by really quickly”, he lamented, but by then it’s bedtime and he falls asleep quickly.

Music also helps, both recorded and performed live.

“There is a small electronic piano up here,” Lu wrote, “that I like to tinker on”. Without a bench to hold himself in place, he was drifting away from the keyboard, so he rigged up a special cord to hold himself within arm’s reach. Lu’s most memorable recent performance was the “Wedding March” when his crewmate went through a proxy marriage ceremony with his fiancee in Houston — another major morale booster all around. Lu and his fiancee, meanwhile, plan to get married next spring.

Santy likened the stresses on Malenchenko and Lu to a tightly-constrained relationship back on Earth.

“In thinking about the psychological challenges of a mission like this,” she said “consider the fact that even very few marriages would be able to sustain unrelenting intimacy in a confined and relatively small space.”

It’s a potentially tense situation, with no other people ever to relate to or to buffer your interactions,” and with “no place to go to get away from the other,” Santy said.

Staying busy, staying honest with each other and staying aware of the outside world’s concerns for them, the two men aboard the space station appear to be doing just fine as isolated crewmates. And their experiences may be excellent out-of-this-world preparation for the even greater psychological challenges, back on their home planet, of beginning their down-to-earth marriages.