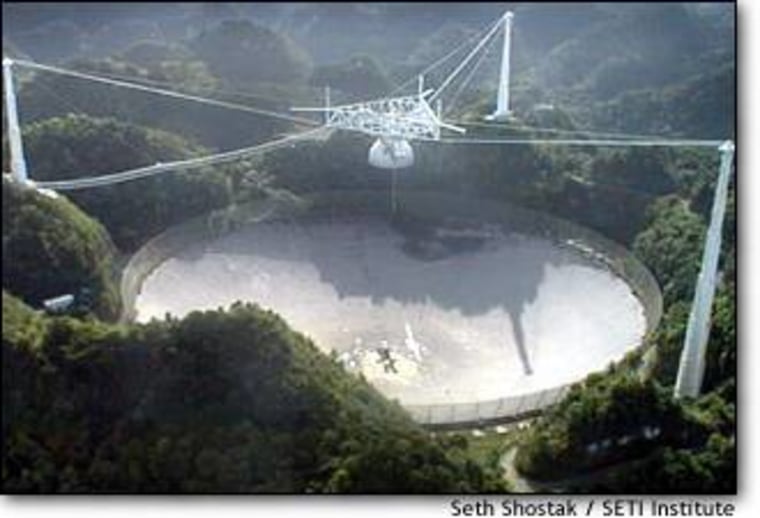

Searching for extraterrestrials is a great subject for lunchtime chatter, but if you actually try to do it, it’s hard work. As a member of the Project Phoenix team, currently camped out at the Arecibo Radio Telescope, I can speak to that.

In the movie “Contact,” eavesdropping on alien radio broadcasts seemed pretty simple. Jodie Foster simply hooked up a receiver to a radio telescope, put on her earphones, and waited for E.T. to phone. Jodie didn’t seem to worry too much about exactly where on the dial she should tune. However, since E.T. hasn’t bothered to send us an e-mail listing his favorite transmitting frequencies, real SETI searches are compelled to listen to as much of the radio dial as they can.

The Phoenix hardware sorts the radio energy collected by Arecibo’s massive metal ear into 28 million frequency channels, and monitors them all simultaneously. Needless to say, the monitoring isn’t done with earphones. Instead, specialized digital hardware checks out each of these channels once per second. If nothing is heard within four minutes, the Phoenix software automatically shifts the bank of 28 million channels up the dial, and listens again. In the course of a few hours, more than a billion frequency channels can be examined for signals.

The problem is that there are entirely too many signals. Project Phoenix, like all SETI searches, is plagued by terrestrial noise – the squeal from nearby radars and orbiting telecommunication satellites. Sitting in the observer’s chair in the dead of night, I watched screen after screen fill up with the spiky interference that litters the microwave bands. An elaborate software system tries to sort out any truly extraterrestrial signals, but it’s a tough slog. An alien broadcast is likely to be weak, and could easily slip by unnoticed in the cacophony of earthly transmissions.

To make sure that doesn’t happen, we rely on a second telescope, in Jodrell Bank, England, to check out likely signals. The use of an additional antenna certainly improves the search, but it also complicates the system.

I envy Jodie Foster. She could sit on the hood of her car with a laptop and those nifty earphones. Jill Tarter and I, on the other hand, nightly face off against three computer workstations and ride herd on programs stuffed with a few hundred thousand lines of custom code. The programs drive the telescopes, collect the data, split it into millions of channels, look for signals, and try to make a decision about whether it’s E.T. on the line or merely a satellite wheeling overhead.

The system is so complicated, it often takes nearly an hour just to get it up and running. As I said, finding cosmic company isn’t easy.

Seth Shostak is senior astronomer at the SETI Institute.

More dispatches from the SETI search:

Sept. 17, 1998: Front line in the search for E.T.

Sept. 20, 1998: Free time and false alarmsMarch 18, 1999: The alien hunters are back at it

March 22, 1999: SETI sleuths track down the glitchesMarch 26, 1999: Expansive musings on a dwarf star

March 31, 1999: SETI's waiting game: Deal with it