Squinting through the aircraft window, I see a bright expanse of ocean below, clotted with white cumulus. Above is a blue-bowl sky, and I suspect that it, too, is clotted. Not with clouds, but with distant worlds peopled by strange beings.

Like Fox Mulder, I am on a hunt for extraterrestrials, although not the type that many claim are buzzing the countryside in high-tech saucers, hoping to interfere with your social life. Instead, I am part of a team of scientists trying to find the aliens where they live: on far-off planets orbiting other stars.

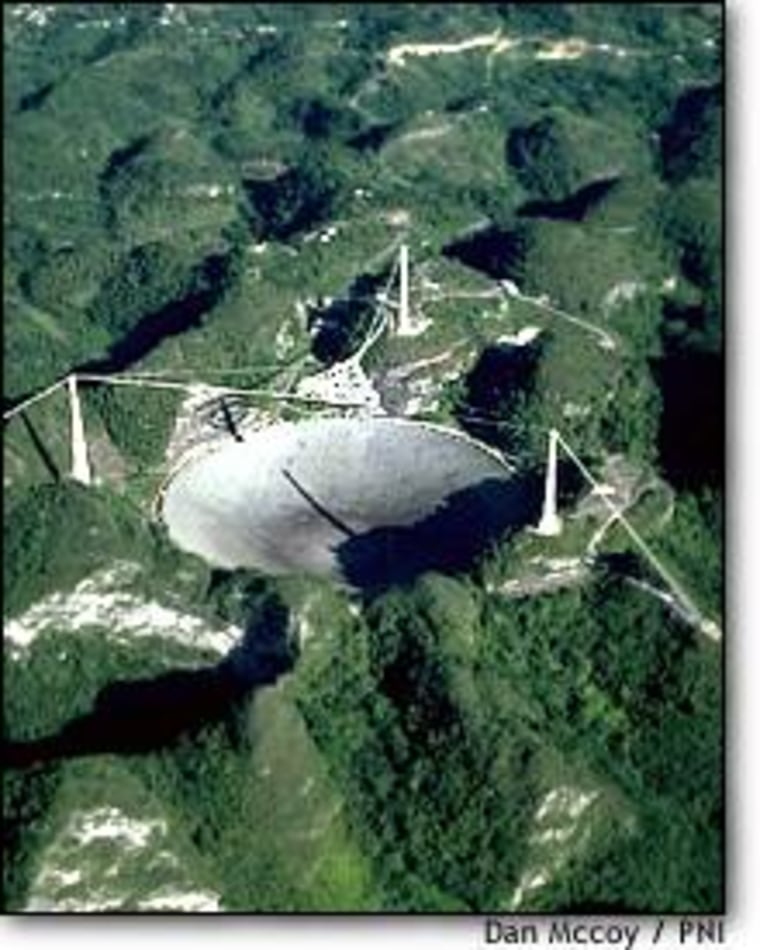

As my jumbo jet roars into the hot sun of the Caribbean, it’s hard to stay mindful of the purpose of my trip. Many fellow passengers, to judge from their baggage tags, are destined for cruises out of San Juan. Others are islanders headed home. But the salubrious climate of these tropical waters is not what draws me southward. Rather, it’s the radio telescope at Arecibo, a monster antenna half hidden in the limestone hills of northern Puerto Rico.

The antenna is situated in a natural bowl, a topographic circumstance that simplified its construction by Cornell University in the early 1960s. But the real reason to put the world’s largest radio telescope here is something else: The closer any telescope is to the equator, the more sky it can see. Folks living in New York never glimpse the famous Southern Cross, while inhabitants of Buenos Aires are deprived of the Big Dipper. But anyone near the equator can catch them both.

Arecibo’s gaze is limited to a patch of sky straight up and about 20 degrees wide, sliding across the universe as the Earth turns. By locating the telescope in tropical climes, that patch intercepts more celestial real estate.

Our experiment is called Project Phoenix, and it’s the most sensitive search for extraterrestrial intelligence going. The strategy is simple: we scrutinize the vicinities of nearby, sunlike stars, hoping to find narrow-band radio signals that would tell us someone else is “on the air.” Anyone who’s seen the movie “Contact,” based on Carl Sagan’s novel of the same title, has a good idea of what the Phoenix team does for a living.

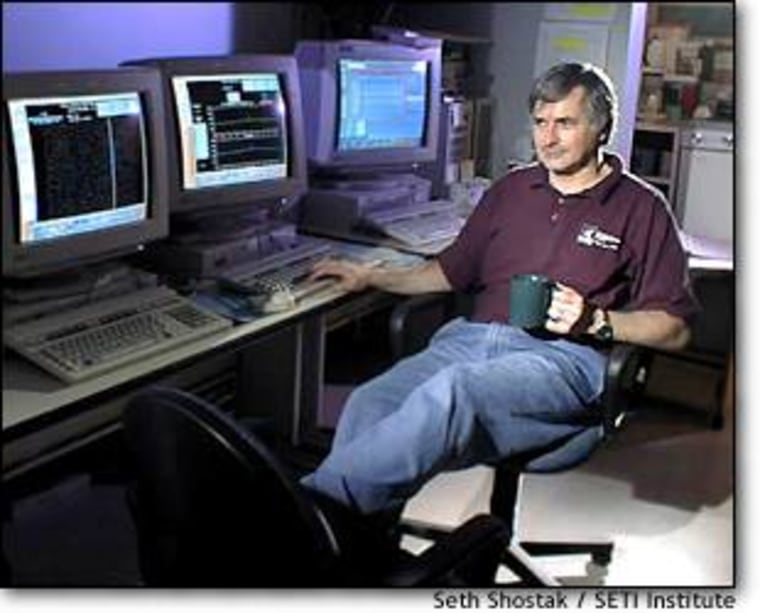

Settling down in front of the computers that control the telescope, I glance at screenfuls of numbers. We’re about to begin the search, and for the next two weeks this small room, filled with electronics, will be my home. The work is frequently dull, but the enticement is enormous. After all, sooner or later it’s bound to happen. The computers will find what no human ear could hear: a faint whistle, a flute played against Niagara Falls — conclusive proof that the universe is home to far more than just us.

Seth Shostak is senior astronomer at the SETI Institute.

More dispatches from the SETI search:

Sept. 17, 1998: Front line in the search for E.T.

Sept. 20, 1998: Free time and false alarmsMarch 18, 1999: The alien hunters are back at it

March 22, 1999: SETI sleuths track down the glitchesMarch 26, 1999: Expansive musings on a dwarf star

March 31, 1999: SETI's waiting game: Deal with it