The telescope was pointed at the star CN Leo. This is not a star among stars. CN Leo is just another of the galaxy’s many dim bulbs, a dwarf somewhat smaller than the Sun. Sure, it’s nearby — a paltry 8 light-years distant — although it would require a good pair of binoculars and perseverance to see this run-of-the-mill runt with your eyes. But of course, we weren’t using our eyes.

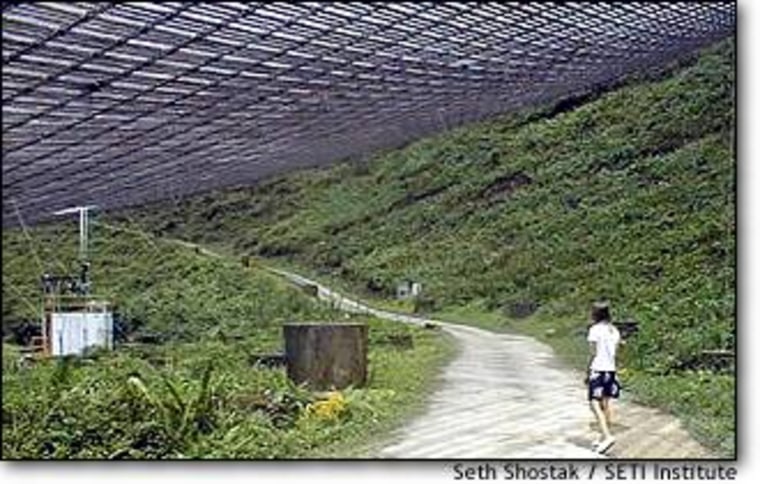

CN Leo was nearly overhead, and Arecibo’s massive metal mirror was positioned to collect any cosmic static that might be coming from the star’s direction. Five hundred feet above the 40,000 aluminum panels that make up the mirror, a large, Bucky-ball structure was inching along a curved track, keeping pace with Earth’s slow spin. Inside were two reflectors that redirect and refocus the incoming radiation onto sensitive, state-of-the-art amplifiers.

The amplifiers, often called “receivers” in casual conversation, boost the strength of the twittering electric and magnetic fields that make up a radio wave, and then feed them into small cables. The cables, looking like silver spaghetti, route the signal through a whole system of microwave plumbing. Ultimately, the incoming energy is sliced and diced in a sophisticated search for the type of signals that only purpose-built transmitters can make.

As a rule, Project Phoenix doesn’t bother with dwarf stars. This is not size discrimination, merely applied astronomy. The faint heat from these stellar lightweights would only suffice to warm planets that orbit close-in. But such planets get “tidally locked” — one side always faces their sun, in the same way that one side of the moon always faces the Earth. Consequently, the climate on these inner planets will probably be less than attractive: fiercely hot on one side, and painfully cold on the other. Not likely to be E.T.’s first choice for a home to phone.

Our favorite stellar targets are the yellow, medium-sized stars that most resemble the sun. After all, we know of at least one case — our own solar system — in which such a star has served as a power plant for a biology-encrusted planet. So the Phoenix hit list has hundreds of sunlike stars on it, all within about 200 light-years distance.

But our immediate neighborhood is special. After all, signals from the closest stars would be stronger and easier to detect. In addition, it might be possible to establish an actual two-way conversation with any extraterrestrials that are so close. So Project Phoenix makes a point of checking out all stars within about 20 light-years - even the unappealing dwarfs with fourth-rate climates.

Besides, just because the weather’s bad doesn’t mean that a planet is inevitably sterile. Maybe we’re giving the dwarf stars a bum rap. A thick atmosphere might smooth out the extremes of temperature somewhat, and besides, scientists are beginning to appreciate how tenacious life is. Biology seems to be tougher than a two-dollar steak.

The night wears on, and the computers quietly click and purr. The hunt for alien societies on worlds around CN Leo continues. So far, silence.

Seth Shostak is senior astronomer at the SETI Institute.

More dispatches from the SETI search:

Sept. 17, 1998: Front line in the search for E.T.

Sept. 20, 1998: Free time and false alarmsMarch 18, 1999: The alien hunters are back at it

March 22, 1999: SETI sleuths track down the glitchesMarch 26, 1999: Expansive musings on a dwarf star

March 31, 1999: SETI's waiting game: Deal with it