When it comes to the technologies required for a human mission to Mars, some experts say it’s mostly a case of “been there, done that.” So why not go? That’s mostly a case of price, priorities and politics.

Despite the best efforts of space-oriented organizations such as the Mars Society, there’s been almost no discussion of space policy on the campaign trail during this millennial election year.

The Mars Society chronicled one of the few exchanges having to do with a mission to Mars, when Vice President Al Gore was asked during a December debate in New Hampshire whether it was time for a commitment on a scale of President John Kennedy’s pledge to reach the moon by the end of the ’60s.

Gore replied that there were two differences.

“No. 1, as the recent two failures of these robotic landers (Climate Orbiter and Polar Lander) show, there’s still a lot we don’t know. Second, the cost is in a completely different order of magnitude as the cost of a moon program,” he said. “There’s no doubt that, eventually, we will land a human being on Mars. But we are right now not at a point of where it makes good sense to outline that.”

NASA’s current concept for an eventual Mars mission carries a price tag of roughly $50 billion, spread out over a decade. That’s about twice as much as the moon program cost between 1962 and 1972 — no small change, to be sure, but not an order of magnitude greater. And Mars Society founder Robert Zubrin says his barer-bones “Mars Direct” program could be done in a decade at a cost of $20 billion, plus $2 billion per mission.

To add yet more perspective to the $50 billion, that represents less than the projected cost of building the International Space Station ... about a third the amount America Online is spending to buy Time Warner ... or about as much as Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates’ net worth has risen since 1997, according to Forbes magazine.

How it would work

Both the NASA design reference mission and the “Mars Direct” plan on which it is based would cost just a fraction of the $450 billion proposal put forth in 1989 — and that’s primarily because each human mission would be preceded by the launch of an unmanned lander that would manufacture rocket fuel from raw materials on Mars.

Such a strategy eliminates the huge cost of sending a spacecraft to Mars with enough fuel for the return trip. Zubrin’s plan calls for combining hydrogen (H2) from Earth with the carbon dioxide (CO2) in Mars’ atmosphere to produce methane (CH4) and water (H2O), with the water broken down into oxygen (O2) and recyclable hydrogen. Methane and oxygen could fuel the return vehicle as well as surface rovers.

“We’re definitely interested in pursuing that technology,” said Douglas Cooke, manager for the Exploration Office at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. But he said that the first Mars astronauts “may not rely on it totally ... we may well send a plant so that they develop fuel for the next crew.”

He voiced particular concern about having contingency plans.

“That’s a weak point in these kinds of scenarios,” Cooke told MSNBC. “If you spend a lot of money and send this big piece of hardware to Mars and something goes wrong, then you’re in a dilemma.”

Although the schedule is in flux, future robotic missions would carry experiments to test techniques for manufacturing propellant on Mars, as well as instruments that would measure surface radiation and examine the planet’s soil and dust for potential hazards to humans.

The orbital mechanics dictate that the best launch window for going to Mars comes around every 26 months. The most efficient transit would take six to eight months each way, with a 400- to 500-day stay on the planet itself.

In his latest book, “Entering Space,” Zubrin says humans could be launched to Mars “by boosters embodying the same technology that carried astronauts to the moon more than a quarter-century ago.”

It may be true that no futuristic spacecraft technology is required — but there are nonetheless myriad technical hurdles to overcome. For example, although a Saturn 5 rocket could propel a “Mars Direct” mission, no existing launch vehicle has enough thrust to do the job by itself. The task would require either building more powerful rockets or assembling the Mars spacecraft in orbit.

Also, much still needs to be learned about how to counter the effects of long-term weightlessness and radiation exposure: Some have suggested shielding the Mars spacecraft with a radiation-blocking reservoir of water, and spinning it in tandem with a counterweight to simulate gravity’s effect. But both concepts are unproven.

Another human factor has to do with long-term isolation: Research conducted at Antarctic outposts and in space indicates that such isolation weakens the immune system — and, of course, there’s the potential for psychological problems as well.

Even if planners can minimize the health risks faced by astronauts during their transit and their risky stay on Mars, there are also environmental concerns to consider: The first step of Zubrin’s plan calls for having a robotic lander set down by itself on Mars with a 100-kilowatt nuclear reactor aboard. That worries MCI executive Vinton Cerf, an Internet pioneer who is involved in the effort to build an interplanetary communications network.

“If we were looking for life on the planet, we might destroy it. ... We have to do it in a way that doesn’t pollute the setting,” Cerf said during a seminar on the Interplanetary Internet.

‘Call to arms'

Resolving all these issues is likely to take at least a decade, and there’s no Kennedyesque kick start in sight.

“Just like you have to have a conjunction of stars in order to get to Mars at the right time, you’ve also got a conjunction of political facts,” said Christopher Kraft, who was involved in NASA’s flight operations from the first days of Project Mercury to the heyday of Apollo. “We in the engineering and science world are not so naïve that we don’t recognize that. It takes a political as well as a scientific effort.”

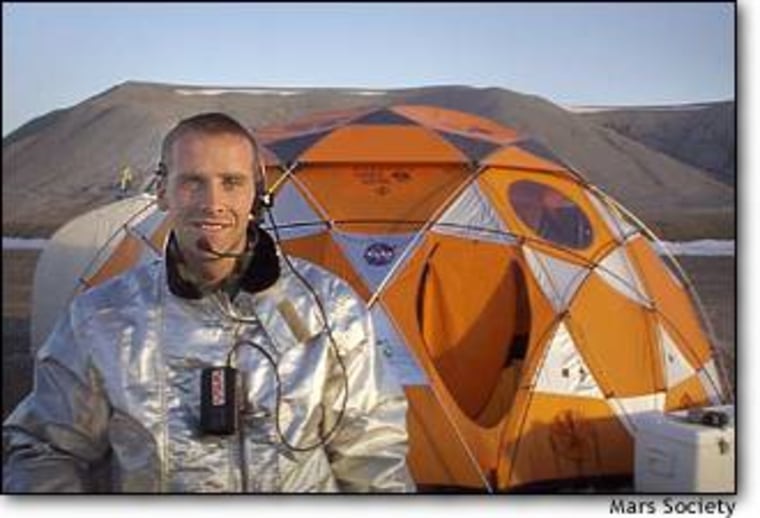

In the meantime, organizations like the Mars Society and the Planetary Society have been taking a lead role in laying the groundwork for an eventual push toward the Red Planet. The Mars Society is developing a habitat for Devon Island in the Canadian Arctic that would serve as the testbed for living quarters on Mars. And on Thursday, the society announced that it would fund an effort to develop a habitable rover that could be adapted for use on Mars.

“What we’re doing right now is a call to arms,” said Marc Boucher, the society’s Webmaster.

He said the design would have to provide living accommodations for two people for a weeklong excursion, capable of traveling 200 miles (320 kilometers) at a top speed of 20 mph (32 kilometers per hour). More information is available via the society’s Web site.

Will movies like “Mission to Mars” help with such calls to arms?

“I don’t think these movies have a tremendous impact on generating public support,” said Louis Friedman, executive director of the Planetary Society.

Rather, he said, the converse was more likely to be true: Moviemakers wouldn’t consider projects like “Mission to Mars” — as well as “Red Planet” and “Mars IMAX 3-D,” the other two films on the calendar — unless the public had a hunger for tales about Mars to begin with.

“It’s an expression of public support that we can point to,” he said.

More about missions to Mars: