In a world full of daily news crisis, this was one of the biggest. On Feb. 3, a North Korean diplomat said the nation had restarted its nuclear reactor at Yongbyon, a clear escalation of the current diplomatic crisis. But the CIA immediately countered the claim, saying the reactor hadn’t been turned on. Since journalists aren’t allowed anywhere near Yongbyon, this was about to become a typical, frustrating diplomatic “he said, she said” story. Until the journalists turned to the sky.

HUNDREDS OF MILES above the earth’s surface, a commercially-owned satellite operated by DigitalGlobe spun into position and — untethered by global borders and government restrictions — photographed the reactor area.

The pictures from Yongbyon, which arrived two days later, were strikingly bland. No recent car traffic; in fact, no activity at all. But most telling: “there was snow on top of the reactor,” said NBC investigative producer Bob Windrem. “So this time, we could confirm what the CIA told us was accurate. Maybe next time, it’ll work the other way.”

EVERYONE A SPY

Next time, the U.S. might be at war with Iraq. Such detailed satellite imagery, the kind once reserved for classified reconnaissance by secret spy agencies, may give the world its first look at war from — some might say — God’s point of view.

“This will be an observed war, I think, to a degree we haven’t seen before,” said Steve Livingston, a George Washington University professor and expert in technology and the media.

Satellite imagery has been a staple of big-news journalism during the past two years, most prominently in the U.S.-China spy plane incident. Images of the U.S. spy plane on the Lingshui military airfield at Hainan Island were seen around the world.

Such pictures weren’t available during the Afghanistan conflict when the Pentagon bought all available commercially-owned satellite images and kept them secret. This time, most experts think such “checkbook shutter control” will be impossible.

But seeing stranded planes or nuclear reactor parking lots is one thing; watching a war from above is quite another. The world might see everything from military encampments, to troop movements, to bomb damage, to refugee camps, to human carnage.

“We’ll see the first battle damage assessments without the administration or Department of Defense hand-picking certain sites they feel will look good on 7 o’clock news,” said Patrick Garrett, associate analyst at Globalsecurity.org, a satellite image consulting firm. “We will be able to see exactly how effective some strikes are.”

WHAT YOU’LL SEE

Both Space Imaging’s “Ikonos” satellite and DigitalGlobe’s “Quickbird” satellite can circle the globe about once every 90 minutes, so it really can be hard to hide from prying cameras.

But there is debate about what images will actually be beamed down from space, and what impact they will have.

While the government hasn’t announced plans to impose limitations, Mother Nature certainly might. Satellite imagery is only as good as the weather, as most cameras can’t see through clouds (only radar imagery, which has other limitations, can).

And while satellites can take a continuous stream of pictures that produce an orbit-shaped image of the planet, the strip is actually relatively narrow — about 6 1/2 miles wide, in the case of Ikonos.

Pointing the camera at a “news event” won’t be realistic unless the visual is relatively stationary, like a nuclear reactor. And image processing and delivery from space to earth — which requires a 423-mile trip, in the case of Ikonos — can take a day or two under the best of circumstances, said Mark Brender, director of Space Imaging Corp’s Washington operations.

“It’s hard for commercial imaging satellites that operate in fixed orbits to chase breaking news or ‘see’ current military operations ,” Brender said. So if war begins, most viewers will see archived satellite images used essentially as locator maps.

Bender says each “special order” image shot to cover a spot news event will cost $5,000-$6,000, imposing a further, economic limitation on how often pictures from above will be used.

Other industry experts expect Space Imaging and DigitalGlobe to offer deep discounts to media organizations, seizing the moment for the best advertising money can buy. And Brender conceded his company will volunteer some images “If there is an opportunity to showcase our technology.”

RESOLUTION AND INTERPRETATION

At just below 1-meter resolution, Space Imaging’s pictures are similar to what airplane travelers see when they look out the window at about 10,000 feet — only objects a meter or longer are visible. Individual cars, and even motorcycles, can be seen. It’s even possible to tell the difference between yellow taxis and other cars. But people, unless they are accompanied by long shadows, are invisible.

That means it is unlikely that individual casualties will be recognizable. There won’t be emotionally evocative imagery that marked the war in Viet Nam coming via satellite cameras, Livingston said.

But it will be possible to spot evidence of large-scale destruction. “If there’s another ‘Highway of Death where you can see hundreds and hundreds of burned out tanks, that will certainly be evocative,” Garrett said, alluding to the images from the 1991 Gulf War.

POTENTIAL FOR PROPAGANDA

It’s debatable how effective the pictures will be in supporting agendas. Colin Powell, in his prosecutory testimony before the U.N. two weeks ago, displayed aerial images as evidence Iraq was playing hide-and-seek with chemical weapons. But viewers saw only small rectangles on a field, and were left to trust Powell’s assertions. The aerial evidence was widely regarded as far less compelling than Adlai Stevenson’s 1961 Cuban Missile Crisis pictures that indicated the presence of Russian missiles in Cuba.

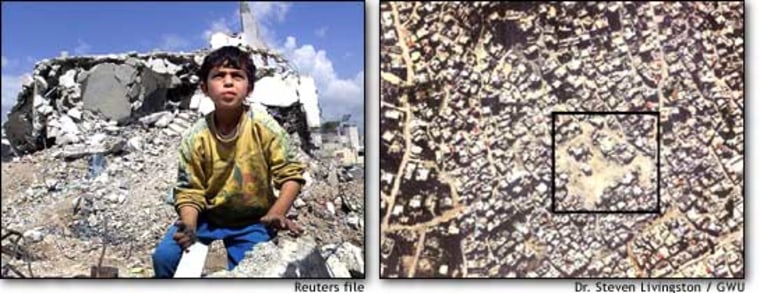

Other governments have tried to use satellite images for propaganda purposes. Last spring, Israel used them to combat negative global reaction after it bulldozed buildings at the Jenin refugee camp on the West Bank. Images from the street showed dramatic destruction of Palestinian homes, suggesting widespread carnage; but images from above showed only a small portion of the camp had been destroyed.

“The tightness of shots from the ground left general impression of devastation,” Livingston said. “But with these images, Israel said, ‘Here’s the part of the camp we surrounded. Here’s exactly where we were ... See how untouched the rest of city was?’ ”

Anne Florini, an analyst at the Brookings Institute, expects the U.S. to use the same tactic when the inevitable question of whether a target was civilian or military arises. “You are going to have to have a lot of faith in the person telling you what you are looking at for it to have an impact.”

That leaves the task of verification to independent analysts, and perhaps journalists, who may or may not be trained for the task. Satellite images are hard to read and can create as much confusion as they clear up.

“Just like in some media today you have those publications at the front end of checkout counter of the supermarket. You’re going to have overhead Paparazzi and tabloid image analysis,” Brender, himself a former TV news producer, said. “That’s a fact of life.”

CBS producer Dan Dubno, who for 6 years has headed an industry task force devoted to preserving journalists’ access to satellite imagery, warned that there are many tactics the military can use to create intentional misunderstandings. Because satellites pass over the earth at predictable times, military planners can order tank turrets reversed, for example, giving the impression of a westward advance when the units are actually moving east.

“They can put things there that make us come up with assumptions that are incorrect, and a relatively innocent press may go along with it,” Dubno said. “Not everything will be as it appears.”