On a crisp autumn morning in 2012, George got a call from his ballot box. He’d been tinkering with his presidential vote on the Netphone for weeks, and had dropped it in the e-mailbox just the night before. Now the election system’s voicemail was calling him back to verify his vote. A recorded message read off the confirmation numbers, as usual — but this time around, the digits didn’t match. George thought for a moment: Was it just a glitch, or did someone actually do what the crypto company said was impossible? Had his vote been hacked?

Ten years from now, that scenario could represent normalcy or a nightmare, depending on what happens between now and then.

On one hand, boosters see online voting as a shot in the arm for an ailing electorate. A small-scale Internet voting experiment in England’s Swindon district helped boost turnout for May’s local council elections by about 3.5 percent, compared with figures from two years earlier.

“It worked beyond our wildest dreams,” election official Alan Winchcombe said.

On the other hand, the glitches bedeviling present-day electronic voting don’t exactly inspire confidence. Statistics from the Caltech-MIT Voting Technology Project indicate that touch-screen machines have performed about as poorly as the infamous punch-card machines over the past 12 years.

This year, Florida is weathering a wave of criticism over problems with touch-screen systems. In Texas, touch-screens had to be taken offline for repairs during early voting because the displays were miscalibrated.

Would Internet voting add to the potential confusion and fraud? Rebecca Mercuri, a computer science professor at Bryn Mawr College and founder of Notable Software, is certain it would.

“We’re taking an inherently insecure medium, the Internet, and layering security on top of it,” she said. “It doesn’t work.”

Why voting is difficult

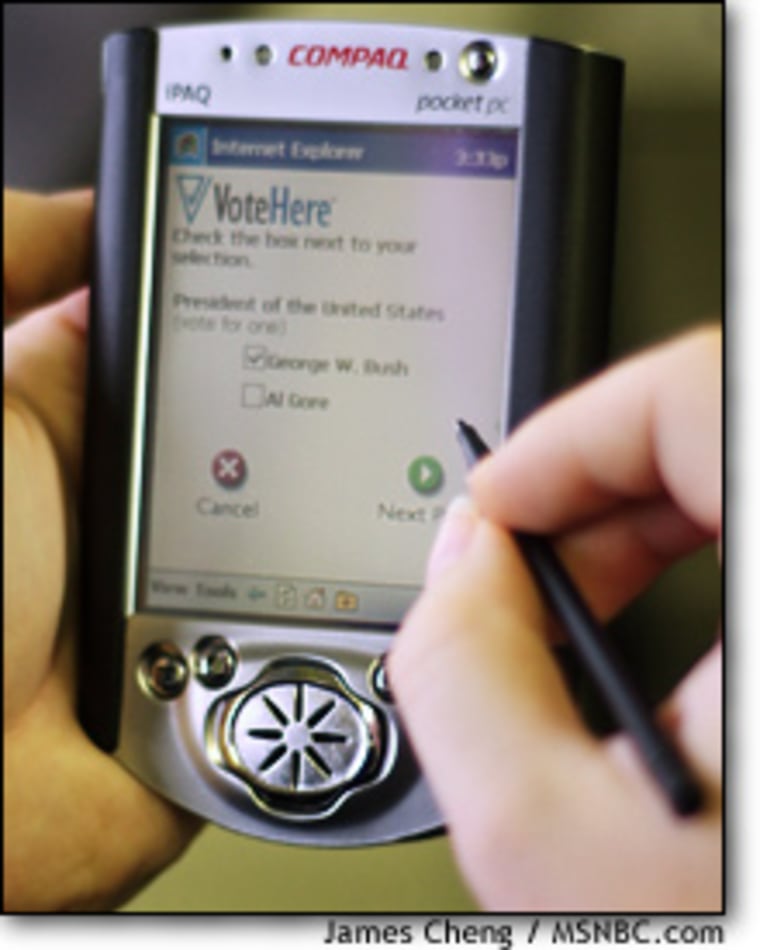

Jim Adler, founder, president and chief executive officer of VoteHere, agrees that Internet voting is a huge challenge. That’s why his company developed the online system that was put to the test in Swindon.

“If this was so easy, banks would be doing elections,” he said from VoteHere’s headquarters in Bellevue, Wash. “We wouldn’t be in this business if we thought elections were as easy as bank transactions.”

He’s willing to put his software up against more traditional voting methods, in hopes of snaring a piece of the billions of dollars in federal funds that will be paid out over the next few years for election reform.

“Give me tough requirements,” he said. “Don’t just give me a red light and tell me we’re never going to go there.”

Why is electronic voting so tough?

“All of the things that make us nervous about doing something by computer are magnified in the voting context,” said Doug Chapin, director of ElectionLine.org, a nonpartisan research center in Washington, “because voting is the first decision which leads to all other decisions. If you believe that democracy is a process, and if there’s any question about the legitimacy of that process, then it strikes at the legitimacy of the government as a whole. Just witness all the navel-gazing that went on in the wake of Bush v. Gore.”

To continue with the banking analogy, it’s OK if the bank knows how much money you have in your account — but it’s not OK if the election office knows how you voted. It’s OK to get a statement from the bank showing your transactions — but it’s not OK to get a piece of paper showing how you voted. And yet, the voting process should leave a verifiable audit trail — not only to guard against election fraud and allow for recounts, but also to ensure that every vote cast is counted.

How the system works

Can Internet voting satisfy all those criteria? VoteHere’s Adler insists that it can, using data encryption, digital signatures and advanced cryptographic protocols.

Voters would sign into the balloting system using two sets of numbers that they received in advance, plus a code based on personal information familiar to the voter. Once they’re finished clicking through the ballot, it would be encrypted and a digital signature would be added.

“As soon as you have encrypted and signed a ballot, it’s in its own little safe,” Adler said. The digital signature serves as evidence that the vote is genuine and has not been altered.

The system could be used to cast a ballot at a polling place, over the Internet, over the telephone — or via a gizmo like George’s.

At the office, the ballots would be recorded in their encrypted form, and then they would be “shuffled,” deciphered and tabulated under the eyes of trusted authorities. If someone wanted a recount, the counters could go back to the encrypted vote register and start over aain. The voter could also check that his or her vote was tallied correctly by matching up verification codes — just as George did in 2012.

“If you have voter verification, you don’t have to trust the machine,” Adler said. “I don’t care if a computer virus upsets my vote, I’m going to detect it.”

Facing reality

During VoteHere’s test in Swindon, nearly 11 percent of the roughly 40,000 voters used the Internet, while about 5 percent voted over the phone.

“One of the political parties was going on, carrying mobile phones (and) saying, ‘If you wanted to vote now, here you go,’” Winchcombe said. That party, the Liberal Democrats, drew the highest number of electronic votes, he said.

Winchcombe said VoteHere monitored the system for signs of fraud and detected “two or three attempts where people were trying to create their own PIN numbers” — but no successful hacks.

Mercuri, however, is skeptical that Internet voting could ever be made secure.

“All of that is completely susceptible to the latest virus attack, the latest denial-of-service attack, sniffers and snoopers,” she said. “There are vendors out there who are trying to mislead the public and election officials into thinking that they have secure cryptography.”

When it comes to remote voting, Mercuri sees nothing that would stand in the way of a voter selling or transferring his or her voting codes to someone else — unless election officials employed an intrusive biometric ID system. She even has her doubts about today’s touch-screen systems: She says such machines should be modified to generate paper ballots, which would be tallied separately to certify the computerized results.

She and other experts say the incentive for fraud or just plain mischief will increase as electronic voting becomes more widespread. Even if new security measures are developed, that would raise new hurdles for voting access, said Caltech Professor Michael Alvarez, a member of the MIT-Caltech voting research team.

“Most Americans aren’t familiar with what a digital certificate is,” he said. “It will require use of a password, and most people forget what their password is.”

Beyond the cybersecurity issue, remote Internet voting raises the same concern about coercion that mail-in absentee voting does, Alvarez said. He said online voting also could accentuate the country’s “digital divide” between high-tech haves and have nots, Alvarez said.

“The folks who don’t have Internet access tend to be elderly,” he noted. “They tend to belong to particular demographic groups. ... Internet voting may run into potential Voting Rights Act problems.”

Proponents of e-voting say that concern could be remedied by placing voting kiosks in government buildings, community centers, libraries and shopping malls. Los Angeles County operated 21 such kiosks for its early voting period this year.

The touch-screen setup, which allowed voters to cast ballots at convenient locations outside their home precincts, was a hit from the very first day. “Some of the locations had people lined up,” said Conny McCormack, the county’s registrar.

Brave new world

Although researchers say the time isn’t yet right for wide-scale Internet voting, they acknowledge that an increasing number of electoral tasks, such as registration and requests for mail-in absentee ballots, will be handled online.

Meanwhile, the small-scale experiments continue. A handful of Americans got a taste of online voting two years ago, in Arizona’s Democratic primary and through an experiment in Internet-based absentee voting for overseas military personnel. Only 84 people voted in the Pentagon’s $6.2 million trial — which worked out to about $74,000 a vote. But Alvarez is gearing up for what he expects will be a bigger federally funded experiment in 2004.

“In the future, we’re probably going to be voting on electronic devices, remotely,” he said. “We’re studying the problem, we’re running experiments and trials. In a decade, we’ll be much closer than we are right now.”