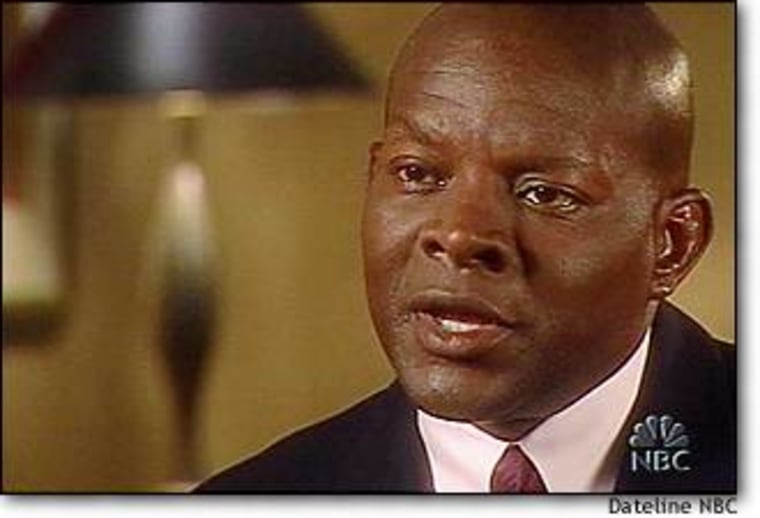

It’s been almost a year since the sniper attacks that terrorized the Washington, D.C., area. Thirteen people were shot, 10 of them killed. One man came to personify the investigation. It was the biggest case of Charles Moose’s career, and may well be his last. He resigned as police chief in Montgomery County, Maryland, two months ago to tell his story in a book. Under the county’s ethics code, he couldn’t accept a publishing deal and remain chief. Choosing the book over the job was not a popular move. But then again, Charles Moose has never been shy about speaking his mind or showing his emotions.

Stone Phillips: “Tearing up in front of the camera, not the image we expect from a veteran law enforcement official.”

Charles Moose: “I’m a very passionate and compassionate person. So, what you saw was who I am.”

With those words and the trace of a tear on his cheek, Charles Moose became the public face of one of the largest manhunts in law enforcement history. The former Montgomery County police chief came with us to the scene of the shooting that had, so unexpectedly, brought him to tears.

This was his first visit to the middle school in Bowie, Maryland where last October 7, sniper suspect Lee Malvo allegedly fired the shot that nearly killed 13-year-old Iran Brown. As we stood in the spot where the sniper once lay-in-wait, Moose acknowledged that something he had said on television, just days before the shooting here, may have actually incited the attack.

Phillips: “You had just told people, ‘Your children are safe.’ But apparently your attempts to reassure the public provoked the sniper?”

Moose: “Yes, and that’s something that, you know, will always be with me.”

Phillips: “Was it a miscalculation on your part?”

Moose: “No. Up to that point, we had no indicator that it was linked to the school, it was the truth. And I think people deserve the truth.”

But the truth was, the snipers were able to strike anywhere, anytime, and the gunshot at this school made that resoundingly clear.

Phillips: “Lee Malvo is quoted as saying that he shot this child to get to you. And seeing you cry on TV he figured he was right, it worked.”

Moose: “I don’t know how he could have known or would have known that was going to be the reaction.”

Phillips: “But, if he was out to upset you, he did.”

Moose: “Well, ‘upset’ might be his word. Certainly I was very concerned.”

In his new book, Moose delivers a candid inside look at the sniper investigation and other events that have shaped his life. He reveals what was behind those public displays of emotion, his concern and compassion, as well as his short-fused fiery temper. That side of Chief Moose erupted two days after Iran Brown was shot. A critical piece of evidence, a tarot card, with a confidential message to police written on it, had been discovered at the scene.

Phillips: “This was your first big break in the case? The first communication from the sniper.”

Moose: “Yes and we wanted—”

Phillips: “And he had specifically asked, ‘Do not share this with the media.’”

Moose: “Yes and we wanted to establish that trust.”

But news of the tarot card and its message, were leaked by someone in law enforcement to a local television reporter and newspaper. They media ran with it, and Chief Moose was not pleased.”

Phillips: “You hit the media pretty hard on this one.”

Moose: “Yes, they were out of line. I mean, I don’t know what promotion or bonus check that person got for releasing that. But it was just inappropriate. And then to tell me that, ‘Well, we just didn’t have time to contact you and see if it was going to be helpful or hurtful. We had to go with it.’ I was very concerned that it hampered our investigation.”

Phillips: “In the book, you called it, ‘Incredibly irresponsible... Today I am absolutely certain that the leak of a Tarot card on the morning of October 7 was a contributing factor in the five shootings that were still to come. I am also certain that the leak of the tarot card slowed down the investigation.’ That’s a powerful indictment. Contributed to the five killings to come?”

Moose: “Communication was hampered, if not cut off.”

Phillips: “Communication between you and the snipers?”

Moose: “Yes. And ultimately communication played a major factor in our ability to close the case. I have yet to have anybody articulate how that station, that newspaper, this community, this nation benefited from having that put out there.”

Dateline contacted the TV station and newspaper, Moose singled out. WUSA told us: “... [The station] had no foreknowledge of the response the information would elicit, nor does it agree with all the conclusions that Chief Moose now draws.”

The Washington Post said: “...We have seen no evidence that our coverage ... compromised the investigation.”

While Moose is not backing off of his criticism, he does have second-thoughts about his tone during the press conference.

Phillips: “You say it was wrong of you to lose your temper.”

Moose: “Well, since I was a little kid, my Dad has always tried to work with me about my temper.”

Born in 1953, Charles Moose grew up in Lexington, North Carolina, the second of three children. His father was a high school teacher, his mother a nurse. Like so many African Americans living in the south during the 1950s, Moose’s family felt the sting of racism. Cross burnings and Klan marches were seared into young Charles Moose’s memory.

Today, at age 50, he still vividly recalls one especially painful incident, his family going for hamburgers after a day at the circus.

Moose: “We get up to the window and a fairly young teenager tells my dad, ‘We don’t serve niggers here.’ Watching my dad have to swallow that and us driving home in silence. Recounting these events in a book, very difficult because I don’t like remembering them. You want to write a book and you just want to be the hero, you want to talk about all the good stuff.”

Phillips: “You write, ‘The issue of black and white is still for me a defining characteristic of life in America.’”

Moose: “Yes, there’s still discrimination. People are treated differently. You never get a day off from being an African American.”

Moose decided early on that education was the key to overcoming racial barriers. After graduating from the University of North Carolina he set his sights on becoming a lawyer but soon realized he’d rather walk the beat, than join the bar.

Phillips: “This was an unlikely career for you?”

Moose: “In my mind. I didn’t start out wanting to be a police officer. I despised police officers. I thought they put dogs on black people. ”

In 1975 he signed on with the Portland, Oregon police department. Rising steadily through the ranks, Moose became that city’s first African-American police chief. He earned a Ph.D. in criminology, and his success in Portland, especially his efforts to improve race relations, led to the job offer in Maryland.

The Montgomery County Police Department had been the focus of a federal investigation for racial profiling. Moose had been on the job there three years, when the sniper case thrust him into the national spotlight.

The investigation spanned three anguishing weeks, much of the time spent searching for a “white box truck,” when suspects Malvo and Muhammad were found driving a dark blue Chevy Caprice. Their arrests were a huge relief, but also raised pointed questions.

Phillips: “Some people question why you didn’t pursue more aggressively the lead that came early on from an eye-witness that a Chevrolet Caprice had been seen speeding away the scene of one of the shootings?”

Moose: “We were also later told by Metropolitan Police Department that that car had been located and that it was burned out, that there’d been a car fire, and it was no longer a vehicle of interest.”

Phillips: “But that wasn’t the only Chevy Caprice that came across the radar screen. I mean, the one that John Muhammad was driving had been stopped by police on numerous occasions.”

Moose: “Yes, that plate is entered. And in the end, when we put that plate in and say how many times has it been entered into various computers, that’s the report that we saw.”

Phillips: “And what was that, it was more than 10 times?”

Moose: “I think it was eight to 10 times.”

They were all routine license checks, the kind patrol officers run through their computers every day. In some instances, police actually spoke to Muhammad and Malvo, and ran a check of Muhammad’s driver’s license. That, too, turned up nothing unusual. But with the Chevy Caprice turning up in the vicinity of so many shootings, shouldn’t that have set off some alarms?

Moose: “In hindsight, when you put it all together, it shows that they were in the area.”

Phillips: “From Baltimore to Richmond Virginia.”

Moose: “Yes. But, it doesn’t mean that they did anything wrong.”

Moose admits that Muhammad and Malvo might have been caught sooner if police had not only run the plates but stopped and searched the two men without “probable cause.” However, a search would have violated their constitutional rights. And it’s precisely that kind of abuse of power that Moose has spent his career trying to stop.”

Phillips: “One of the big criticisms is how wrong the FBI profile was. And how long you seemed to cling onto that. White male, working alone, in his 30s.”

Moose: “Let me be very direct. The FBI behavioral scientist profile team never put race on the profile that they gave to us.”

Phillips: “The FBI profile did not specifically mention that this was most likely a white man?”

Moose: “No, they did not.”

But Moose’s own book seems to contradict that. In it, he quotes the profile: “Historically cases similar to this series have been perpetrated by white males.” Still he insists, that was merely a guideline and claims race was not used to rule out suspects.

Moose: “We stressed it over and over and over again. ‘Keep an open mind.’”

Phillips: “Perhaps the most serious criticism is that after communicating to the snipers that you wanted to talk, the people manning the phones failed to recognize them, when they called.”

Moose: “Yeah, I wish we could have only hired perfect people.”

Phillips: “One of your police officers had a three minute conversation, it turns out, with one of the sniper suspects. A man claiming to be the sniper, using some key phrases. And at one point he yelled at the officer, ‘Do you know who your dealing with? More people are going to die if you don’t talk to me.’ How does a phone call like that not get flagged for immediate investigation?”

Moose: “I would just encourage you to understand how many of those calls that we got. Whether or not there should have been some way to take each call and move it to the front, if we do it that way, then it’s just a fiasco.”

Moose says a thousand calls an hour were coming in to the sniper task force, generating a thousand leads a day. In the end, it was information generated by a phone call that linked the snipers to another murder in Alabama. A fingerprint left at that scene, pointed to Lee Boyd Malvo and his traveling companion, John Muhammad.

Phillips: “Do you think these suspects, if convicted, deserve the death penalty?”

Moose: “If the jury sees it that way, then certainly I would be in agreement with that. It’s a very difficult position for me, because so many people that look like me, African-American males are on death row, some justifiably, some in error. So it pains me, but I’ve been involved in this case, these people are not inappropriately charged, there’s not been any making-up of evidence. If they get the death penalty, there was no doubt that they deserve the death penalty.”

Moose has never come face-to-face with either of the two suspects and told us he doesn’t know what he’d say to them if he did. The meeting that mattered to him came just hours after the arrests, with the families of the victims.

Phillips: “I wanted to tell them that I was sorry that we hadn’t got it done sooner.”

Phillips: “A personal apology.”

Moose: “Yes.”

The pressure to crack this case was enormous. Charles Moose says failure, for him, was simply not an option.

Phillips: “Do you think you put more pressure on yourself in this case, this investigation, because of your race?

Moose: “I don’t know if it’s just this case. I would say that that’s the reality, period. The reality has been, equal is still not good enough. I think as an African American in America you have to be better. Is that in my mind? Is that not reality? I don’t know. It is my reality and therefore it is my truth.”