Wildfires are part of the life cycle of forests, but the nation watched in horror last summer as firefighters tried and failed to smother some of the biggest fires as they swept through prime recreation land and destroyed property. Now forestry experts are openly debating an age-old question: Should wildfires be stopped at all costs, or should they be allowed to play their role in thinning forests?

For decades this debate has never been out in the open; fire was considered the enemy.

Don Smurthwaite, a spokesman with the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise, Idaho, said the U.S. Forest Service has believed in suppressing fires since the turn of the century. The defining moment for this policy came in August 1910, when a series of wildfires in Idaho and Montana destroyed 3 million acres and killed 85 people.

“That fire caught the nation’s attention and after that point the Forest Service, a brand-new agency, became more and more accepting that all fires should be suppressed,” said Smurthwaite.

Attacking fires became an even stronger mandate, he said, during the devastating season of 1930, when fires consumed an estimated 52 million acres. In comparison, the fire season of 2000 has consumed 6 million acres.

But the policy of suppression is now being seriously questioned. Decades of stopping fires has led to a dangerous buildup of plant growth that is feeding fires at lower elevations. That is what was happening this summer in the Black Hills of South Dakota and in Montana.

In April 1999, the General Accounting Office reported that 39 million acres in national forests in the interior West were at “high risk of catastrophic wildfires” because of unchecked vegetation. The GAO said the management practice of putting out wildfires disrupted the historical occurrence of frequent but smaller fires that cleaned out this undergrowth. In short, the office called much of the region a “tinderbox.”

One way of looking at the problem is to compare the forests of the turn of the century to today’s forests. A hundred years ago, it was not unusual to find 30 to 40 trees to an acre, each 2 feet or more in diameter. Today, there are between 200 and 300 trees to an acre with an average width of perhaps 5 inches. Today’s forests are sickly and in desperate need of being thinned out, which is why prescribed fires are becoming more popular.

The new way of thinking is that fire isn’t good or bad.

“It’s like sunshine and rain,” said Allen Mattison of the Sierra Club. “Fire has a very natural role in the forest.”

AFTER YELLOWSTONE

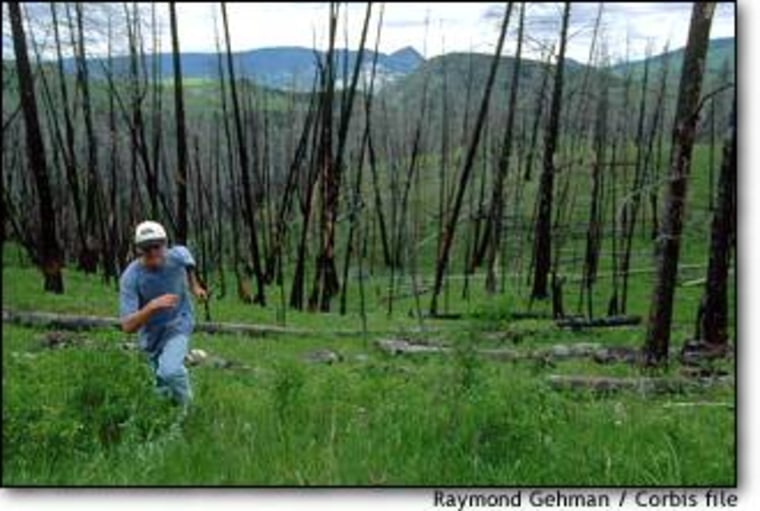

This new awakening to the role of fire hit home after the 1988 Yellowstone fire that destroyed 600,000 acres in the nation’s crown jewel of parks.

At the time, the fire was considered devastating and grabbed national headlines. But 12 years later, experts say the fire really didn’t do that much harm and actually was beneficial.

“From an ecological standpoint, the fires in 1988 didn’t do any damage,” said Bill Romme, a fire ecologist at Fort Lewis State College in Durango, Colo. He said no existing plant or animal species were greatly reduced and there was no serious erosion.

“Throughout the burned areas, you see young forests blooming,” he said.

Ecologists say several species only live in burned-out forests such as the three-toed woodpecker, mountain bluebird, tree swallow, wild geranium and dragonhead flower. Some trees, like the lodgepole pine, only reseed when their cones are heated. If fires were eliminated, then these species wouldn’t survive.

Romme said the U.S. Forest Service first began experimenting with allowing natural fires to burn in Yellowstone Park in 1972 and found that a majority of fires just went out by themselves. By 1975, he said natural burns became part of the park’s fire policy as long as the fires didn’t threaten human life, property or significant resources.

The policy was working until 1988, one of the most severe fire years in history. It didn’t rain all summer in the Northern Rockies and there were 50 to 60 mph winds all season. When the park was torched, the federal government immediately put a moratorium on natural fires and prescribed fires, said Romme. But two years later, he said, the government concluded that the country needs fire in wilderness areas like Yellowstone and said it is appropriate for lightning fires to take their course.

RAGING DEBATE

This summer, however, the government was not taking that tactic. All government agencies were mandated to fight all fires this summer. In many cases, it was a futile effort and the debate has centered on why some of the fires aren’t left alone, especially if they are beneficial to some habitats.

“There’s no question we should be fighting fires when they are threatening human structures,” said Cathy Whitlock, professor of geography at the University of Oregon. “But in wilderness areas, I don’t know why we are fighting fires because fires are part of the ecosystem. ... I think everybody is just so gun shy about fires [that] they are fighting them everywhere.”

Romme said he thinks the government was taking a strict view on fighting fires last year because of what happened last spring with the runaway prescribed fire in Los Alamos, N.M., that destroyed several homes.

Added Whitlock of the current firefighting effort: “I think it is a bit of a show for the public.”

She said what was happening with the fires is something that happens in higher-elevation forests every 200 to 300 years.

“It’s hard to say ‘don’t overreact’ when fires are burning through your town, but historical records show that higher-elevation forests burn every few centuries and tend to be large fires that occur during dry periods,” she said.

There’s very little many firefighters can do.

Dennis Knight, a forest ecologist at the University of Wyoming, said fires at the higher elevations are almost impossible to control because they rage on the tops of trees in what are known as crown fires.

“I’m not saying you shouldn’t fight these fires once in awhile, but in some areas the data suggests the fires are going to occur no matter what we are going to do,” he said.

Fires at lower elevations are more apt to be near towns so there are less options for firefighters.

But deciding what to burn and what not to burn in such an extreme fire and drought season changes the game, said Walter M. Thompson, assistant director of stewardship at the Nature Conservancy in Florida.

“The best thing to do with the public safety and all involved is to do everything that can be done to put these fires out,” he said.

Thompson is a big proponent of prescribed fires and has overseen some 600 controlled burns. The former firefighter said the 2000 fire season was just too unpredictable to take chances with letting a fire rage, especially with the dangerous buildup of vegetation in some forests.

Thompson said the government should conduct more prescribed fires to clean up forests and prevent such raging wildfires in the future.

Others point out that every acre of federal land has a fire policy and say the U.S. Forest Service knows what it’s doing.

“How much firefighting is too much and how much firefighting is not enough is always a difference of opinion,” said Doc Smith, a former smoke jumper who has been fighting fires for 42 years. But he said he is convinced the country has some of the best fire management talent in the world.

“I can rely on those folks to make the best judgment,” he said. “Someone has to sit in that chair and make those calls, and those folks that are doing that are good.”