The Bush administration’s decision to engineer a dramatic and unexpected shift in global currency strategy reflects its growing nervousness about the steady loss of U.S. manufacturing jobs, economists say. With the presidential election just over a year away, and the rapidly expanding economy still creating no jobs, the change announced by the Group of Seven industrial countries appears aimed at least partly at defusing the issue of China’s strong currency, which threatens to become a potent U.S. political issue.

In a statement issued Saturday in Dubai, the United States and its G7 allies declared for the first time that “more flexibility in exchange rates is desirable for major countries or economic areas to promote smooth and widespread adjustments in the international financial system.” From a group that for years has sworn allegiance to “exchange-rate stability,” the communiqué marked the biggest stated policy change in “decades,” said Jeffrey Frankel, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.

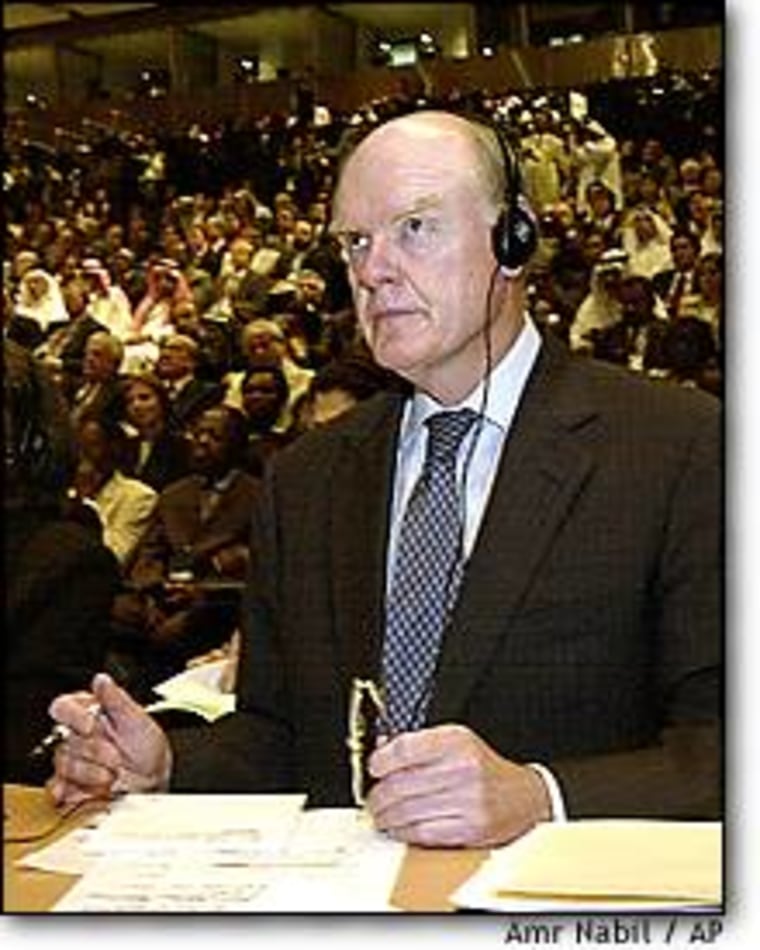

He and other experts said Snow persuaded allies to make the change largely for political reasons. With fiscal and monetary policy stretched near their limits, pushing down the value of the dollar — particularly against Asian currencies — is the final lever the administration can pull to generate jobs in an economy that otherwise is expanding impressively.

“The context is pretty clear,” said Frankel, who was an economic adviser in the Clinton administration. “This is something the White House wants to do so it has something to say in an election year when people in manufacturing states say, ‘What are you going to do? We’ve lost so many jobs.’”

Others agreed, including Greg Valliere, chief strategist for Schwab Washington Research Group. He pointed out that Snow and two fellow Cabinet secretaries “got a boatload of grief” from manufacturing communities in two Midwest states they visited in a whirlwind tour over the summer.

On Labor Day, visiting a job-training facility in Ohio, Bush announced he would appoint an official to boost employment in what he called the “hurting” factory sector. Manufacturers have shed jobs for 37 straight months, a total of 2.7 million jobs or more than 15 percent of the total.

“They at least want to be portrayed as leaving no stone unturned,” said Valliere. “They want to feel our pain. They want to appear to be engaged.”

The G7 statement was welcomed by manufacturers as a “very important affirmation” that Chinese exchange rates in particular are a problem for the entire industrialized world, said Frank Vargo of the National Association of Manufacturers.

“This is not just the United States. This is the industrial countries saying the time has come to fix this problem,” said Vargo, who follows international economics for the trade group.

In theory, a weaker dollar makes U.S.-produced goods cheaper overseas, boosting exports and profits. A weakened dollar also could make foreign-made goods like Japanese cars more expensive. But currency exchange rates generally change slowly, and the impact takes many months to work through the economy.

“The idea you could get a whole bunch of new manufacturing jobs that could be in place by next November’s election — it just doesn’t work that way,” Valliere said. “We’re going to see job growth, but whether this policy will help on that front — I have my doubts.”

He suggested that the exchange-rate shift was a pre-emptive strike, aimed at keeping a lid on the dollar as the U.S. economy begins to heat up. The U.S. economy widely is expected to post growth of 5 percent or more in the current quarter, which would be its best performance since 1999. Such rapid growth, especially in comparison with more slowly expanding economies in Japan and Europe, would tend to attract investment in U.S. stocks and bonds, driving up the value of the greenback.

In moving to keep the dollar capped, the administration runs the risk of spooking financial markets, and letting the dollar drop too far, too fast. That would make it harder to attract the foreign currency needed to fund the nation’s gaping trade and budget deficits. The result would be higher long-term interest rates, crimping growth prospects.

Stocks have fallen in the aftermath of the G7 move, partly because of concern about the increased risks introduced by the new policy, analysts said. OPEC’s surprise decision to cut oil production also pushed stocks lower Wednesday.

“In the best of worlds they would like to see the dollar weaken, but certainly not a free fall,” said Jay Bryson, global economist at Wachovia. “They are walking a fine line, but to the extent they can put pressure on the Japanese currency they think that’s a good thing.”

Although manufacturers have expressed the greatest concern about the relatively high value of the Chinese currency, which is fixed to the U.S. dollar, China is not part of the G7 and needs to be addressed either separately or indirectly. Alex Patelis, a senior foreign exchange strategist at Merrill Lynch, said in a note that China may have been consulted before the G7 issued its statement and could be planning to revalue its currency.

In the absence of any Chinese action, attention has turned to Japan, which has prevented the yen from rising too rapidly this year by intervening in foreign currency markets, buying about $10 billion a month in U.S. dollars, analysts said. So while the dollar has fallen 34 percent against the euro since peaking in February 2002, it had fallen just 13 percent against the yen as of last week. On a trade-weighted basis, the dollar has fallen just 8 percent over that time period, reflecting in part the $103 billion trade deficit with China.

After the G7 statement the dollar fell sharply, hitting a three-year low against the yen, although it stopped short of that level Wednesday after a top Japanese official cautioned that the Bank of Japan would intervene again if necessary. Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary Yasuo Fukuda said Japan would act as needed in currency markets, calling the yen’s rise this week “harsh.”

Similarly Snow declared that there has been “no change in the strong-dollar policy.” But traders dismissed the comments of both Snow and the Japanese officials. In the past, Snow has provided an idiosyncratic definition of a strong dollar, describing it as a “good medium of exchange” and something “hard to counterfeit.”

As for the Japanese, traders have little doubt they will continue to intervene in foreign currency markets. The question is, how aggressively?

“In many eyes this isn’t over until the Bank of Japan indicates what is the level they want to defend,” said Tony Crescenzi, chief bond market strategist at Miller Tabak & Co. “Most feel the Japanese are willing to let the dollar fall against the yen into a new zone. But what is the new zone? That is the question many would like to see answered.”