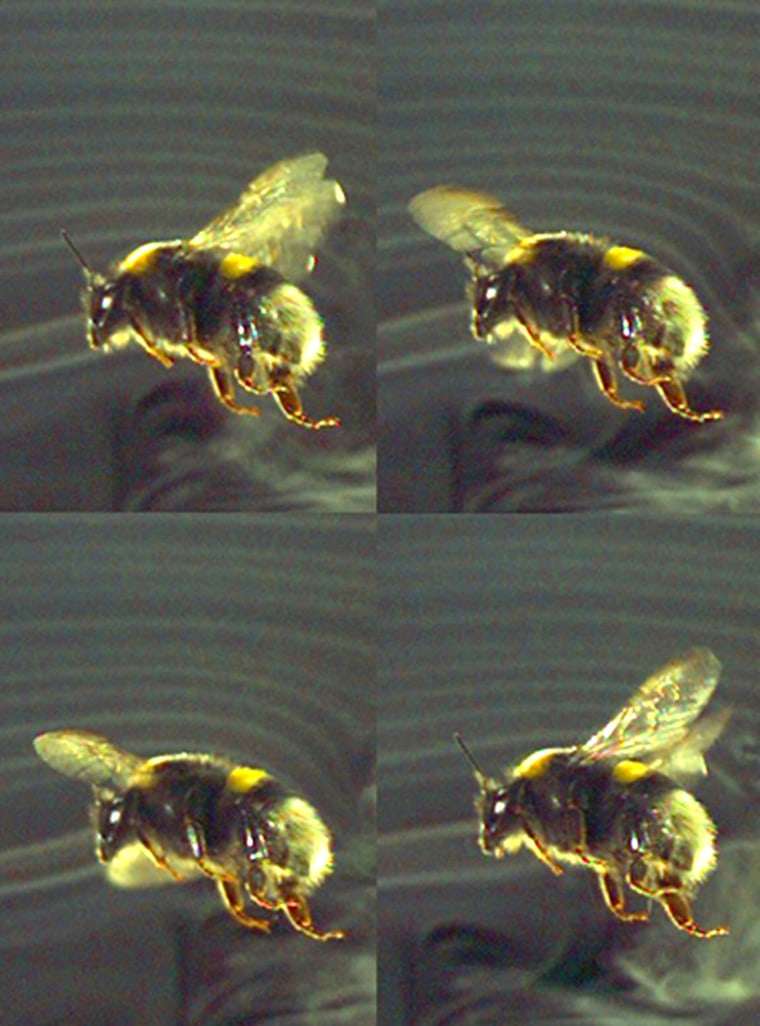

Scientists have taken a close look at the way bumblebees fly, and the video footage isn't pretty.

Unlike soaring eagles, graceful butterflies, and swiftly swooping bats, bumblebees are heavy and wide. Their wings are short. And according to the new study, one wing flaps out of synch from the other.

The work suggests that bees sacrifice aerodynamics for precision as they navigate from flower to flower, said Adrian Thomas, a biomechanics professor in the department of zoology at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. His study was the first to look at real bees instead of insect robots or computer models.

"Brute force may well be the answer in many cases where efficiency isn't important," Thomas said. "Efficiency is important for the hive, not for an individual bee."

Thomas and colleagues were motivated by an urban myth. As early as 1919, some aerodynamicists argued that, according to the laws of physics, bees shouldn't be able to fly at all. Yet, they obviously do.

Since then, and especially during the last decade, researchers have made significant advances in understanding how insects move through the air. One finding is that basic rules of aerodynamics — which explain how airplanes and some birds fly — simply don't apply to bees, which flap their wings 200 times a second.

Nevertheless, the bee myth continues to hang around. And despite research on flies, butterflies, dragonflies and other insects, no one has focused on bees, let alone real live versions.

Thomas and colleagues set up a wind tunnel that was 1.5 meters (about 5 feet) long, with flowers on one end and a beehive on the other. As 100 trained bees buzzed their way through the tunnel, high-speed cameras captured up to 2,000 frames each second. Lines of smoke filled the tunnel, allowing the scientists to study vortexes formed around each flapping bee wing.

After many hours of analysis, the researchers were surprised to see the left and right wings operating independently. Bees didn't use their entire wingspans to generate lift, making them less efficient than they could have been.

The scientists hypothesize that a bee's inefficient movements allow it to turn quickly and with a fine sense of control.

"We often assume that animals are flying in a way that is perfect so they're not wasting any energy," said Douglas Altshuler, a biologist at the University of California, Riverside. "The truth is that animals can behave in so many different ways."

Since bees subsist on high-energy nectar, Thomas said, conserving resources might not matter much in some situations, like in a fairly low-stress wind tunnel, where the insects flew at speeds of about 1.5 meters per second. When commuting long distances in the field, on the other hand, bees can cruise at 10 meters per second. In those cases, they might move more efficiently.

While those details remain to be investigated, Altshuler said the new study is a significant step forward.

"This is really providing us the first glimpses of the flow patterns and aerodynamics of real animals," he said. "And that's really wonderful."

The work might also help fulfill one of the military's long-standing goals: To create tiny flying instruments that can maneuver into tight spaces and take pictures.