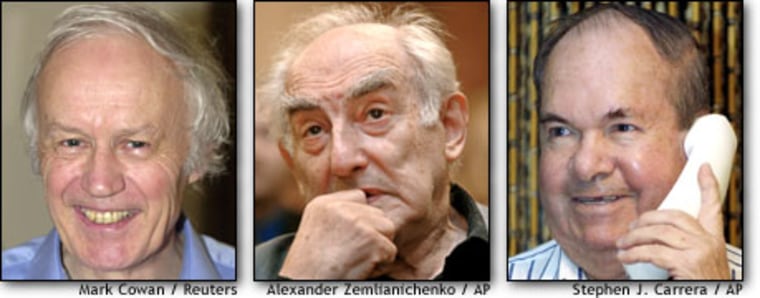

Two American citizens and a Russian won the 2003 Nobel Prize in physics Tuesday for theories about how matter can show bizarre behavior at extremely low temperatures. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences cited Alexei Abrikosov, Anthony Leggett and Vitaly Ginzburg for their work concerning two phenomena called superconductivity and superfluidity.

Abrikosov, 75, IS a Russian and American citizen based at the Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois. Ginzburg, 87, is a Russian based at the P.N. Lebedev Physical Institute in Moscow. Leggett, 65, is a British and American citizen based at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The $1.3 million prize money will be shared equally among the three winners.

Leggett said he was surprised. “I guess it had occurred to me that it was a possibility I might get the Nobel Prize, but I didn’t think it was particularly probable.”

Abrikosov, on the other hand, said the news didn’t shock him. He said he had been nominated several times before, but this year the Nobel committee notified him that he was a candidate. “And since this had never happened before, I saw this as a good sign,” he said.

“I feel now relief,” he said. “I had lost hope of winning ... But I thought my life is good even without (the Nobel Prize). I have interesting work. I am happy. I love my family.”

Reached by phone at the Lebedev institute, Ginzburg said he had long given up hope of ever receiving a Nobel.

“They have been nominating me for about 30 years, so in that sense it didn’t come out of the blue. But I thought, ‘Well, they’re not giving it to me, I guess that’s it.’ After all, there are a lot of contenders. So, you know, I had long ago forgotten to think about this.”

Asked how he was planning to celebrate, he said: “I haven’t thought about it yet. Now I’m supposed to write a paper and if I’m healthy, I’ll go to Sweden.”

Superconductivity and superfluidity

The two phenomena the researchers studied are linked, in that superconductivity arises from how pairs of electrons behave, while superfluidity comes about from pairings of atoms.

Superconductivity is the ability of some materials to conduct electricity without resistance when they are chilled to extremely low temperatures. Superconducting magnets are used to produce powerful magnetic fields for the standard body scanning technique called magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI. Other discoveries concerning MRI were honored Monday with the Nobel medicine prize.

Researchers hope to harness superconductivity for such uses as power lines that can conduct current without waste to resistance and high-speed trains that float above the tracks.

Abrikosov and Ginzburg were honored for theories about superconductivity that they started developing in the 1950s.

Leggett, meanwhile, applied ideas about superconductivity to explain how atoms behave in one kind of “superfluid” in the 1970s. His theory has proven useful for other fields of physics, like the study of particles and of the universe, the Swedish academy said.

Superfluidity occurs when liquid helium is chilled to near absolute zero, the coldest anything can get. The liquid begins to flow freely with little apparent friction. It can even climb up the sides of a beaker.

Phil Schewe, a physicist and chief science writer at the American Institute of Physics, said superfluidity doesn’t appear to have as many applications as superconductivity. But “it may well prove to be important just because it is so odd,” he said.

The Swedish academy said researchers can use superfluid helium to study other physical phenomena, like how order can turn to chaos. Such research might illuminate the ways in which turbulence arises, “one of the last unsolved problems of classical physics,” the Swedish academy said.

A WEEK OF NOBELS

This year’s Nobel awards started last week with the awarding of the Nobel literature prize to South Africa author J.M. Coetzee.

On Monday, American Paul C. Lauterbur, 74, and Briton Sir Peter Mansfield, 70, were selected by a committee at the Karolinska Institute for the 2003 Nobel Prize for medicine for discoveries leading to development of the MRI body-scanning technique.

The winner of the Nobel Prize in chemistry will be named on Wednesday morning and the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel later the same day.

The winner of the coveted peace prize — the only one not awarded in Sweden — will be announced Friday in Oslo, Norway.

Alfred Nobel, the wealthy Swedish industrialist and inventor of dynamite who endowed the prizes, left only vague guidelines for the selection committees.

In his will he said the physics prize should be given to those who “shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind” and “shall have made the most important discovery or invention within the field of physics.”

The academy, which also chooses the chemistry and economics winners, invited nominations from previous recipients and experts in the fields before cutting down its choices.

The prizes, which include a gold medal and a diploma, are presented on Dec. 10, the anniversary of Nobel’s death in 1896, in Stockholm and in Oslo, Norway.