Apparently, the song was right: The revolution will not be televised. It will be thumbed.

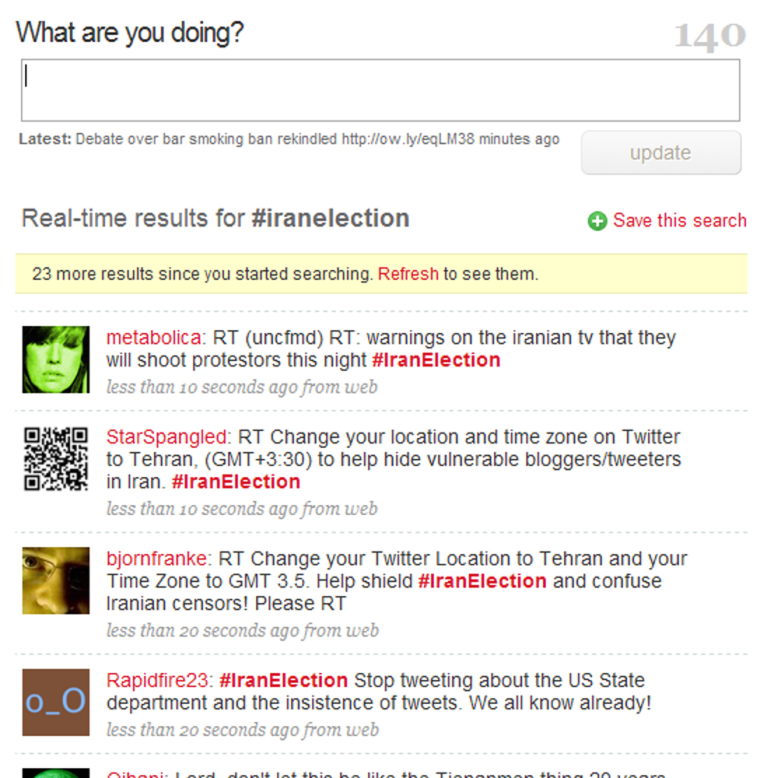

With traditional reporting silenced and with Iranian e-mail and Web services shut down by the government Tuesday, much of the information about the election protests in Tehran was coming through social media sites such as Twitter.com and Facebook.com.

Many users of social media sites access them through cell phones and messaging services, which use different pathways from the World Wide Web circuits that Iranian censors have labored to shut down.

“They’ve cut off telephone, e-mail, texting, and for foreign press issued a letter saying nobody can report without permission,” the Center for Arab and Iranian Studies in London said in a statement. “Twitter is the one thing being used.”

At least it was except for about 50 minutes beginning at 5 p.m. ET — overnight in Tehran, after things calmed — when Twitter went down for what it said was “a critical network upgrade.”

The upgrade had originally been scheduled for Monday night, but the U.S. government persuaded Twitter to postpone the work so as not to silence the protesters. A State Department official said the United States wanted to highlight “Twitter’s role as an important means of communication — not with us — but horizontally in Iran.”

Twitter said it delayed the blackout as long as it could, but it said the work was necessary “to ensure continued operation of Twitter.”

“Our partners are taking a huge risk not just for Twitter but also the other services they support worldwide — we commend them for being flexible in what is essentially an inflexible situation,” it said.

Online scramble for contributions

Twitter was commanding the lion’s share of the attention, but users were documenting the protests on other social media sites, too, while reporters for the mainstream media were confined to their hotel rooms and offices.

Facebook.com was the home of active amateur reporting. One Facebook page, named simply Iran, had more than 20,000 followers, some of whom were trying to organize new protests for Wednesday in Tehran.

Thousands of images were being uploaded to Flickr.com, a photo-sharing site, while videos purporting to capture demonstrators’ being beaten — and, in at least one graphic posting, killed — were being published on YouTube.com.

Sites run by mainstream organizations, such as msnbc.com and CNN.com, tried to get in on the action, inviting users to send their photos and videos to them, instead.

“People who have been silent forever are coming forward,” said Omid Memarian, an Iranian journalist and fellow at the University of California-Berkeley, who said he was following the protests on Twitter. “They're saying, ‘We want out voices to be heard.’ ”

An electronic battle of wills

Social media’s short messages aren’t as comprehensive as an Associated Press report, and the photos aren’t magazine quality. And while much of the material could not be independently verified, at least it was real-time — for many incidents, it was the only news available.

Tuesday afternoon, messages from people claiming to be witnesses to the demonstrations flowed into Twitter at the rate of hundreds a minute. Posts would flood in, only to slow to a trickle for a minute or two as Iranian censors sought to stanch the flow of information. Then posts would resume in a torrent as users found ways around the censorship.

At the same time, hundreds of thousand of page requests per second were being made in a coordinated attack on Iranian government Web sites, rendering them inaccessible, said Gary Warner, director of computer forensics research at the University of Alabama-Birmingham. The tactic is called distributed denial of service, or DDOS.

“Previous large-scale DDOS attacks were organized more at the grassroots level, where participants were part of an exclusive community,” Warner said in an analysis distributed by UAB. “By employing a lower point of entry like Twitter as a tool in the cyber war, all that the attack organizers need is for Twitter users to click the attack links, and the Twitter users’ computers instantly become a part of the cyber war.”

Warner cautioned that DDOS attacks were illegal under U.S. law, carrying up to a year in prison, even though “users may think clicking a Twitter link to a certain Web page is an innocent way of supporting the anti-government opposition in Iran.”

One Twitter user called the communications battle “cyberwarfare at its best,” and there were unconfirmed reports that Iranian security forces were fighting back by creating their own Twitter accounts to spread their version of events.

More on