Sunday, June 28, marks the 40th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, considered by many the beginning of the modern gay rights movement in the U.S. NBC News Editor Sandra Lilley spoke to two men, one who was at the Stonewall Inn on the night of the riots and the other a historian who wrote a book about the events. They discuss how the movement for gay rights has, and hasn’t, changed over the last 40 years.

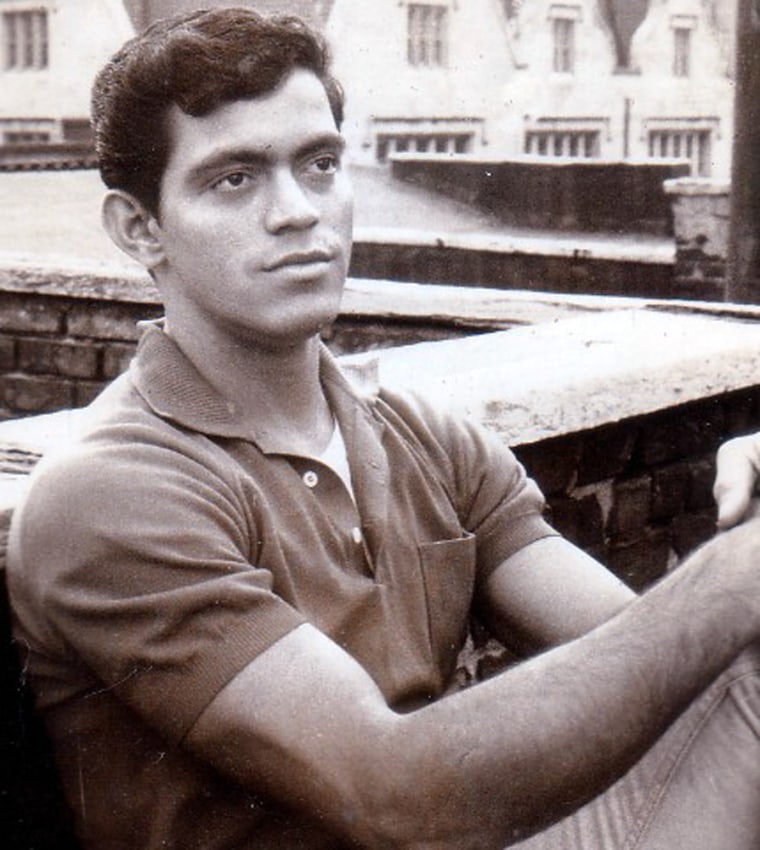

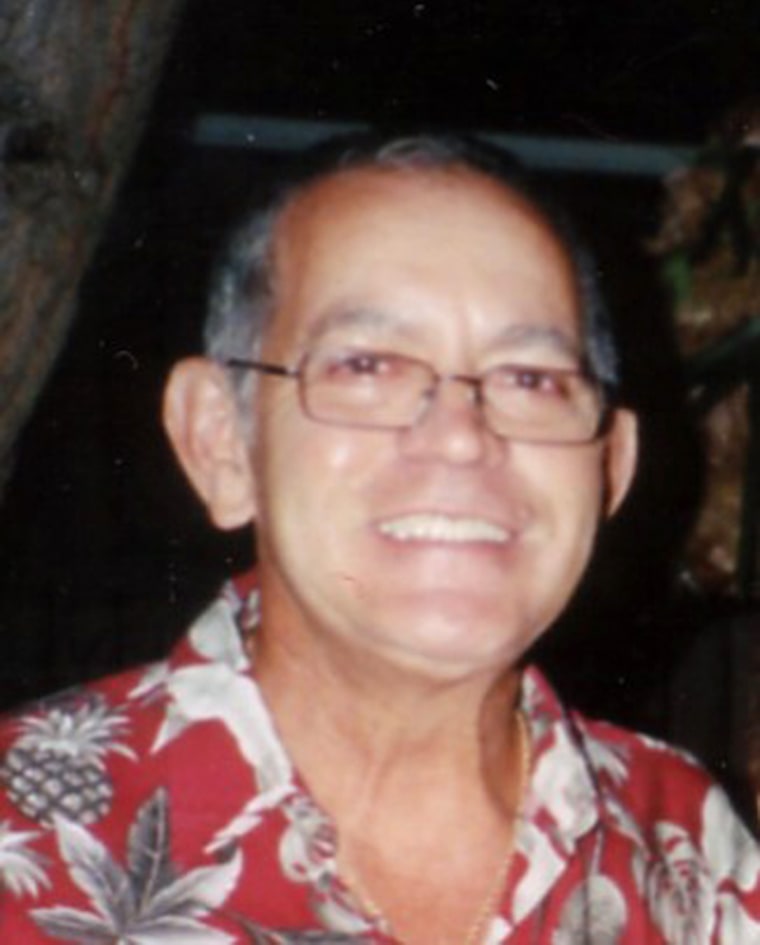

Raymond Castro lives a happy suburban life at his house on the water near Tampa, Fla.

Now 67, the semi-retired baker who lives with his partner of 30 years, Frankie Sturniolo, enjoys helping out his neighbors and spending time with family and friends. “All my neighbors treat me so well; they love me and they depend on me. I check on their pets, I mow their lawns…I have keys to three or four houses surrounding me.”

Castro’s tranquil life seems a long way away from events on June 28, 1969, a night that ushered what many consider to be the beginning of the modern gay rights movement: The police raid at the Stonewall Inn, a popular gay bar in Greenwich Village, a then-bohemian neighborhood in New York City.

“When the police raided the place, I was outside,” Castro remembered. “Then I remembered a friend inside who did not have a false ID and he was going to get in trouble, so I went inside to give him one.” (Many of the police raids, he said, resulted in arrests for underage drinking). “Once I got inside, the police wouldn’t let us out. It got really hot. I remember throwing punches and resisting arrest. The police handcuffed me and threw me in the paddy wagon. But I sprung back up, like a leap frog, and when I did that I knocked the police down.”

Castro was arrested and spent a night in jail. The riots continued for several days, but Castro did not go back.

“I disappeared into thin air after the arrest,” he said, and returned to his work at a bakery in Brooklyn.

A different era

In fact, it was not until David Carter, a historian and author of “Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution,” called Castro that he started publicly reflecting on the events of 40 years ago.

“We went to the Stonewall because it was one of the few places where you could be yourself. You could dance, you could hold hands with someone you liked. In most other places, you could not show any signs of emotional expression. If you were walking along the street and you put your arm around somebody else the police would harass you. They would pull you over, see if you had drugs. And if a gay guy was beaten by a straight guy nothing happened, you couldn’t even press charges,” Castro recalled.

“Gay men were so afraid of the police,” said Carter, the historian. “It was considered so outrageous for gay men to gather on the street. At the time, many local residents in Greenwich Village did not like this concentration of gay people so they put pressure on the politicians to clean up the neighborhood. It was common for a police officer to take a billy club out and hit a gay man on the legs and say ‘Move on, faggot.’”

Carter added that in some cases, “Undercover cops chatted up the men, even followed them from bar to bar. When a gay man accepted a ‘drink’ or an invitation, they were arrested. In the mid-1960s, more than 100 men were arrested every week in New York City for gross indecency and public lewdness.” He added that after some of these arrests, “employers would get calls. So many lost jobs, or were disbarred or had licenses taken away.”

“In my case, I didn’t ‘look feminine,’ and I was never picked on,” said Castro. “But you had to be in the closet. If they found out you were gay you could get fired from your job. I didn’t have any of those problems – I was one of the lucky ones.”

Leading a ‘double life’

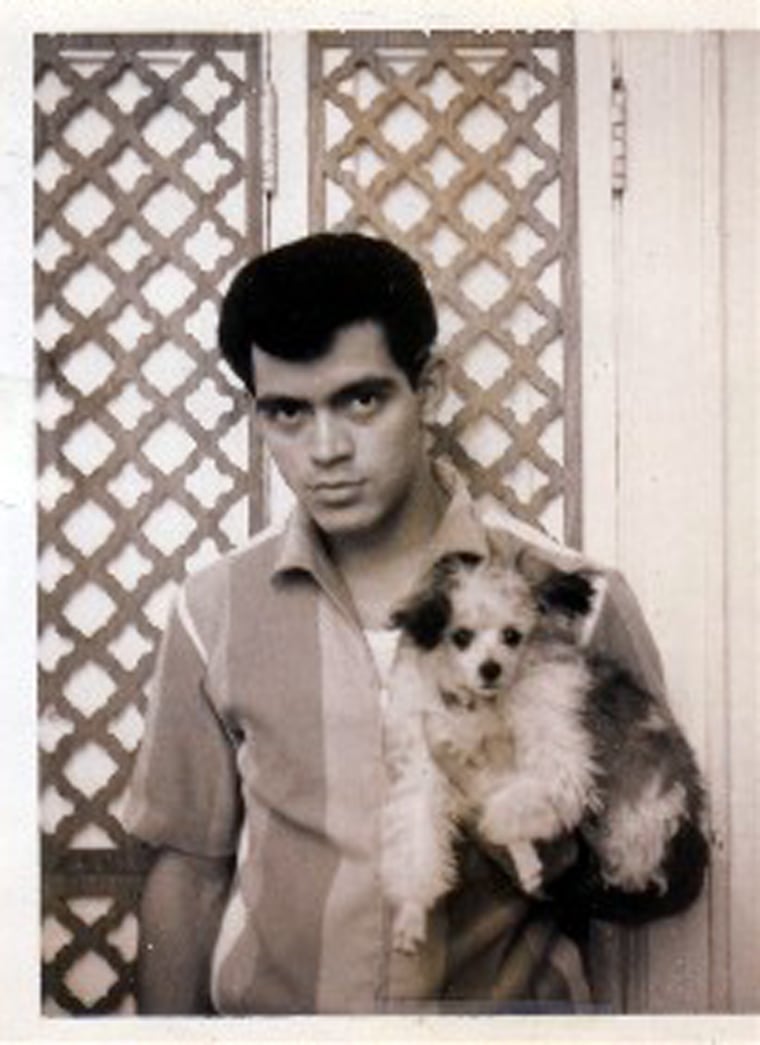

But Castro, like many others, made compromises along the way. “I did live a ‘double life,’” he said.

“I even got married in 1962 when I was 20. We never had children and there was no love there.” His said his wife knew he was gay. After a few years, his wife, who was from Colombia, went back home. “It made it easier to have pictures of her and to present a double life to people whom I was dealing with.”

As for Castro’s family, he grew up with a single mother in a housing project in Spanish Harlem. “I don’t know if she (his mother) knew I was gay. It was never discussed. As I got older, around 17, I think she knew. It’s one of those things a mother knows, but she didn’t speak about.”

Castro does remember one unpleasant instance, however. “My mother had a boyfriend. One day he was drunk and he told me he was going to rape me. I told him I would get him first. He never threatened me again.”

A different struggle now

Fast forward four decades. “My partner Frankie’s family is Sicilian. A few years back, I had to meet Frankie’s dad.” Castro did not know how it would turn out. “At the end of the evening, Frankie’s dad turned to me and said, ‘You’re one of us.’”

And when Sturniolo’s mother was diagnosed with cancer, Castro told his partner to bring her to live with them. “I cared for her,” he said. “She was my family.” She was with them until she passed away.

Castro says the situation for gay people is much improved over the past four decades. “I think people are more tolerant and understanding now,” he said. “I personally don’t come across any bigotry. Neighbors don’t think you’re going to molest their kids or their husbands.”

But he is still angry that gay marriage is only available in a few states.

“I would like to see same-sex marriage, he said, “but I don’t want to have to leave the state of Florida to get married. It should be a federal law.”

“We’ve been together so long,” he said of his 30-year partnership with Sturniolo, “that the only thing that’s going to separate us is death.”

But, he added, “If I drop dead, I can’t pass my social security to Frankie. If I didn’t have a will, there would be no guarantees that I could leave everything to my partner.”

Carter was more blunt: “In terms of federal legislation, the gay movement is exactly where we were in 1969.” Four decades after Stonewall, “there is only a patchwork of civil rights laws in only some states which provide some protection to gays.”

The reasons are varied, he believes. “Some blame is on politicians who have been too timid and don’t want to take a risk. But we also have to spread the blame on gay organizations. They should be registering more voters and distributing legislative literature. Many gays don’t even know we have no federal protections. We have to be more focused and effective.”

A place in history?

Carter also believes that it’s important that the history of the gay rights movement is taught to future generations.

“Another place we have to make great progress on is in terms of history. I grew up in Jessup, Georgia. That was a place where many hated MLK. Yet 15 years after his death, we were learning about Brown versus Board of Education in school. Does the average teenager know about the Gay Liberation Movement or the Stonewall Riots? If there is no legitimate discussion, we can’t be taken seriously. Our struggle is not seen as American history or civil rights history.”

Castro is more patient.

“I don’t think I’ll see a federal law for gay marriage in my lifetime,” he said, “but it will get there eventually. It’s like a slow-moving train.”