On a gray, rainy Sunday afternoon, Russian families gather along the shores of this bay to catch gorbushka — a fish more plentiful than potatoes in these parts, and tastier. The bay is located on the southern end of Sakhalin, an island in the Russian Far East, north of Japan.

But Nikolai Yablochkin, 39, who sells the fishing permits, is worried that in years to come there won’t be any more fish. His fear is that the booming oil and gas development going on off the coast of Sakhalin by companies including Texas-based ExxonMobil will destroy the island’s pristine environment and the schools of fish that are the lifeblood of most people here.

“People catch fish here so they’ll have something to eat for the winter,” Yablochkin says. One example of the development? Near where Yablochkin stands, a plant to convert natural gas into a liquefied form is being built. Where fishermen now throw their lines to hook gorbushka, two jetties will stick out into the bay.

Two projects worth $22 billion

With its rich oil and gas reserves, Sakhalin has attracted billions of dollars in foreign investment. But many environmentalists and locals worry about the ecological damage the development could bring.

One project, called Sakhalin-1, is 30 percent owned by ExxonMobil and controls fields with estimated recoverable reserves of 2.3 billion barrels of oil and 17 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

“It’s one of the largest in ExxonMobil’s world portfolio,” says Michael Allen, government and public affairs manager for Sakhalin-1.

The second project, called Sakhalin II, is partially owned by Royal Dutch/Shell and has estimated reserves of 600 million tons of oil and 24 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

Combined, their total investment should be about $22 billion — not bad on an island where the average wage is $268 per month.

Environmental concerns

But at Sakhalin Environment Watch, a local environmental organization, Natalia Barannikova says the environmental costs could outweigh the economic benefits.

Top among her worries is possible oil spills. Under the ExxonMobil project, oil will be piped from fields on the northeast side of the island to a terminal at De-Kastri on the Russian mainland. From there it will go through the Tartar Straits by tankers, using icebreakers in the winter.

Barannikova is worried one of the tankers could run into problems. In 1989, the Exxon Valdez hit a reef after avoiding ice floes in Alaska’s Prince William Sound — spilling 11 million gallons of oil.

“All this coastline is an area of commercial fishing. Up to 1,000 vessels can be simultaneously fishing in the Tartar Straits in summer,” says Barannikova.

But Allen says the company has already done a number of successful test runs through straits and adds that only double-hulled modern tankers that will be constantly checked for safety will be allowed in. “Prevention is the key. Aggressive prevention at all stages,” Allen says.

On land, different problems arise.

Sakhalin Environment Watch objects to Sakhalin Energy’s proposed pipeline running from the fields in the northeast to Prigorodnoye. Specifically, they don’t want the pipeline built underground, saying it will be difficult to detect leaks — a major concern in this earthquake-prone area.

Rachele Sheard of Sakhalin Energy says the company decided it was safer to lay the pipeline underground. The company has leak detectors throughout the pipeline, will do visible checks of the route and send sensors through the pipeline to check for irregularities, Sheard says.

The Shell and ExxonMobil pipelines will also traverse more than 1,000 streams, rivers and lakes — all vital to the region’s fishing industry.

Sheard says when crossing main salmon spawning rivers, the company will use special drilling techniques to dig under the water without disturbing the river’s flow. Much of the work is scheduled to be done in the winter when the rivers are frozen.

But environmentalists worry this might not be enough protection, especially considering that 8 percent of the population works in the fishing industry.

Western gray whales like this one off Sakhalin now share feeding grounds with oil platforms.

Whales feed between fields

Another issue sparking international attention is the plight of the approximately 100 Western gray whales that feed along Sakhalin’s northeast shore every summer.

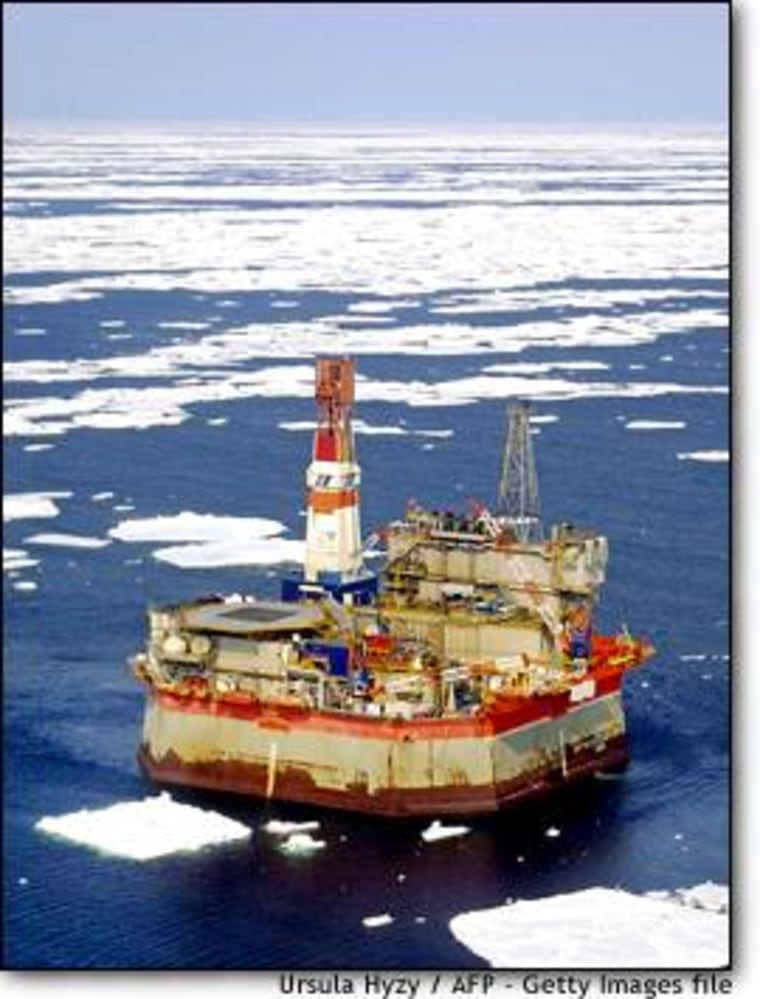

Whale researchers and environmentalists worry the critically endangered mammals won’t survive the oil and gas activity. The whales’ feeding grounds are located between Sakhalin Energy’s fields to the south and the ExxonMobil fields to the north.

“The whole area will be boxed with pipelines and platforms,” says Grigory Tsidulko, who is part of a research team studying the whales every summer. Whether “the noise will affect the whales we don’t know, but we’re concerned.”

But the oil companies have also spent about $5 million to research the whales’ situation. They say they’ve modified their actions to protect them, and the results so far are positive.

“There’s been no discernible impact on the whales,” says Sheard. “They keep coming back year after year.”

Better than Soviet-era drilling?

Even the deals cut by the government with the oil companies to develop the fields are generating controversy. Some Russian politicians and environmentalists say under the deals, which allow the oil companies to avoid most taxes for years, there will be little economic benefit for the island. Sakhalin government officials and the oil companies say without these deals, it is unlikely any foreign oil company would have come here in the first place.

Ultimately, many who work in the island’s oil industry say it’s inevitable that some company will drill for oil and gas near Sakhalin — and it’s better for the environment if it’s a foreign company.

“Because Exxon and Shell are here, it’s got international environmental attention,” says Todd Crossett, a partner with Sakhalin-Alaska, a consulting firm on the island. “If it was just Sakhalinmorneftegaz (a local, Russian oil company) out there developing this, it would be off the radar.”

Back on Prigorodnoye Bay, people begin to pack up their coolers of fish and go home after a day of fishing.

Yablochkin, for one, says that while fishing is important, he feels the oil and gas development may be beneficial if done correctly.

Making 2,700 rubles a month, slightly less than $100, he delights in a parting thought: “There will be good jobs,” he says.

Rebecca Santana is a freelance journalist based in Moscow.