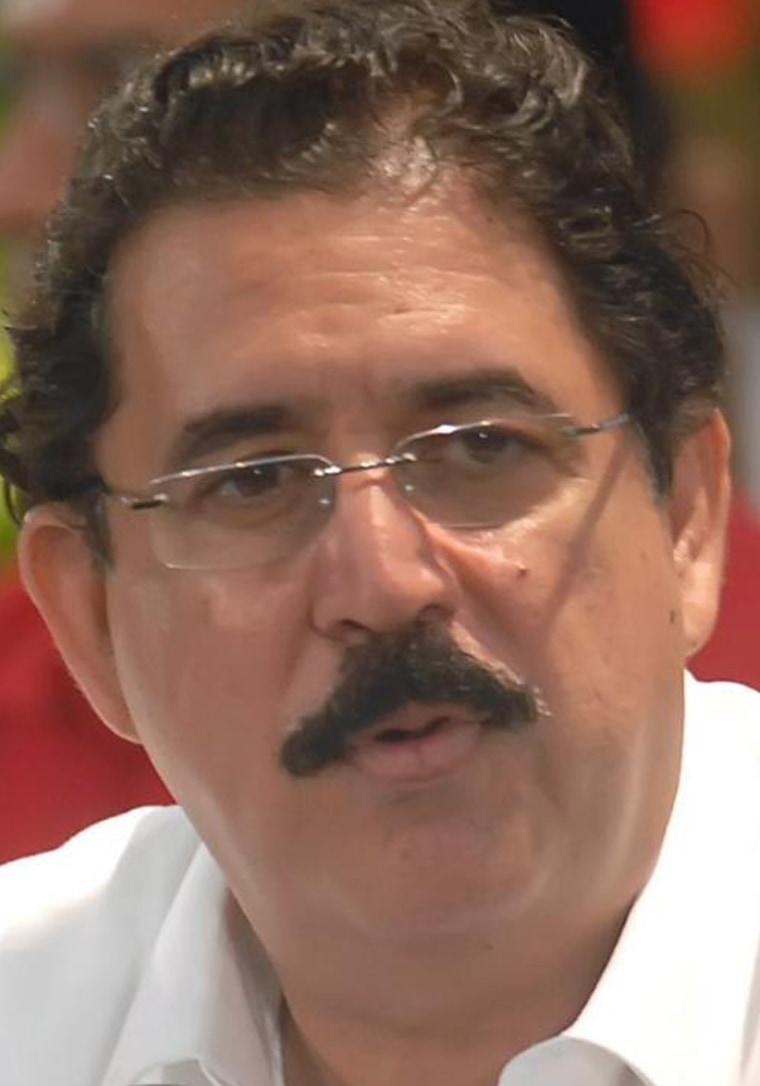

A tall, wealthy rancher with a black mustache and a white Stetson, Manuel Zelaya spent the last three years turning the political system on its head. At public events, he hurled insults at the rich and powerful, sometimes reinforcing his points by breaking into song.

Now those leaders have turned against him, backing the soldiers who ousted him Sunday in Central America's first military coup in 16 years.

Thousands of Hondurans celebrated in the streets in 2006 when Zelaya won the presidency as a frank-talking populist who lambasted the rich — despite his own wealth — and pledged to combat corruption, poverty and crime.

Those promises remain largely unfulfilled. Corruption has dogged his government with several officials accused of taking kickbacks. He doubled the minimum wage but most businesses have refused to pay it, saying they can't afford it amid a global financial crisis. And violence has surged, rising 25 percent from 2007 to 2008 to make Honduras one of Latin America's deadliest countries.

Zelaya's government struggled from the beginning, and asked the United States for help. But he says his pleas went unanswered. So he turned instead to Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, who promised $300 million in aid last year and gave Honduras subsidized fuel.

The son of a timber and cattle baron, Zelaya studied industrial engineering but dropped out to take over his family's agricultural business in eastern Honduras.

He became active in the Liberal Party in the 1980s and went on to serve in Congress three times, becoming a vocal supporter of decentralizing the government and giving more power to communities.

Zelaya 'was never a real leftist'

His bid for the presidency came out of nowhere, but Zelaya quickly gained support by painting himself as a man from the countryside who understood the rural poor and would combat crime by fighting poverty.

Zelaya "was never a real leftist growing up," said Heather Berkman, a Central America expert with the New York-based consulting firm Eurasia Group. He became more radical after becoming president and finding a convenient partner in Chavez, who could help fund his social programs, she said.

He also became increasingly confrontational.

Last year, he refused to submit the government's budget to Congress, fueling accusations that his allies are stealing from the coffers.

His government declared it had the right to monitor phone conversations, though officials say they stopped tapping after a month because of the public outcry.

Zelaya has been embroiled in disputes with media outlets, accusing them of criticizing his government for economic gain, and in 2007 he ordered all radio and TV stations to broadcast his almost daily speeches.

"His own political party, his former vice president — they were all against the actions he was doing," Berkman said. "No one knew how much he was spending. He had no coherent budget policy and his government was doing a terrible job on combatting rising poverty, crime, things like that."

Changing the constitution

On Sunday, Zelaya had planned to hold a referendum asking Hondurans whether they would support efforts to change the constitution. The Supreme Court, Congress and the military leadership opposed the vote, fearing he would use the referendum results to try to run again in violation of Honduras' constitution, though Zelaya denied that.

He fired the military chief last week for refusing to support the referendum and vowed to ignore a Supreme Court ruling reinstating him.

Hours before balloting was to begin, soldiers whisked Zelaya from his residence and flew him to Costa Rica.

He now finds himself in exile with virtually no political allies at home. Congress named one of Zelaya's top opponents to replace him — a member of his own party.

Yet many of Honduras' poor remain loyal to Zelaya for his anti-rich rhetoric and words of empowerment.

"He was really a good president," said Jesus Almendares, a 30-year-old farmhand. "They criticize him a lot, but he improved life for a lot of people."

Zelaya said he would seek to return to his country Thursday and reclaim control of the government. He said he would accept an offer from the head of the Organization of American States to accompany him to Honduras.