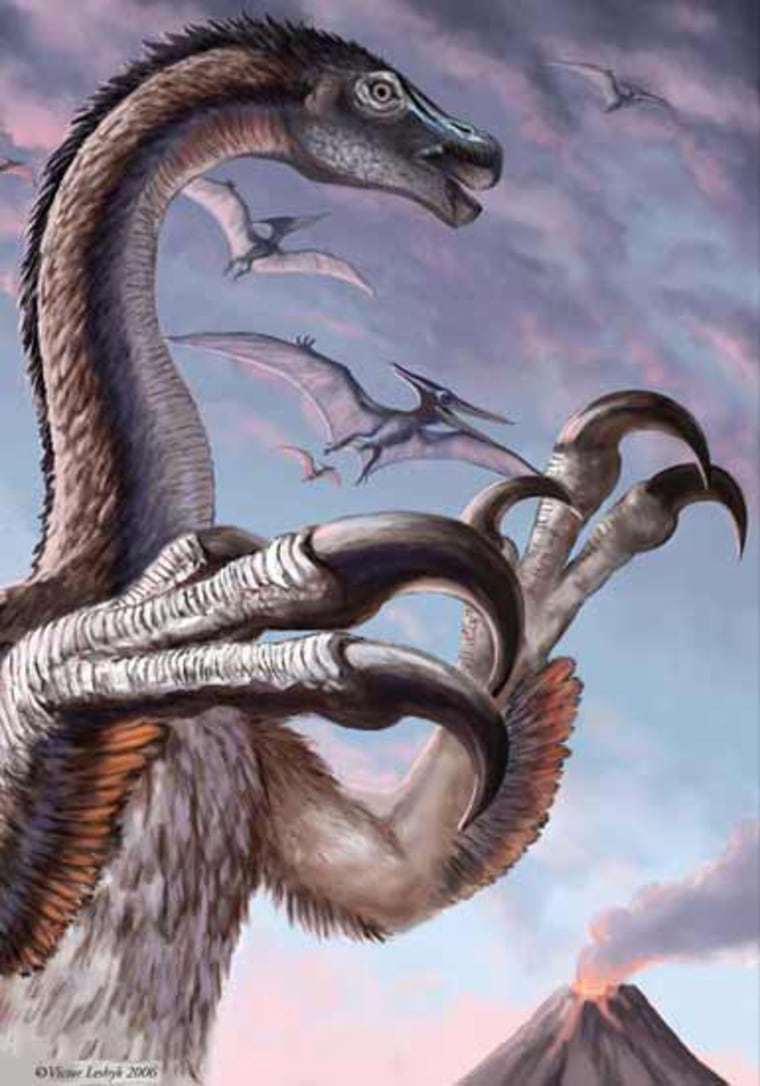

A multi-institutional team of scientists this week reports the discovery of a giant new dinosaur in Utah, Nothronychus graffami, which stood 13 feet tall and had nine-inch-long hand claws that looked like scythes.

Its skeleton, described in the current issue of Proceedings of the Royal Society B, represents the most complete remains ever excavated of a therizinosaur, meaning "reaper lizard." It is one of only three such dinosaurs ever found in North America.

Lead author Lindsay Zanno told Discovery News that therizinosaurs, including the new Utah species, "are unusual in that they have small heads with a keratinous beak at the front of the mouth — the same material as the beak of modern birds — and small leaf-shaped teeth."

"Their bellies are proportionally enormous, supporting large guts," added Zanno, who is a researcher in the Department of Geology at The Field Museum. "They have greatly enlarged claws on their hands, short legs and tails, and four-toed feet."

Therizinosaurs are theropod predatory dinosaurs, a group that includes the legendary Tyrannosaurus rex. The newly discovered 92.5-million-year-old Utah dinosaur was no lightweight either. As Zanno said, "You wouldn't want to run into this guy in a dark alley." But its teeth, beak, gut and other anatomical characteristics suggest it was an omnivore that mostly feasted on plants.

Co-author David Gillette, curator of paleontology at the Museum of Northern Arizona, told Discovery News the formidable-looking claws on Nothronychus graffami probably weren't used to kill other large animals, but instead might have tackled "digging into termite mounds, mucking on the bottom of a lake or pond like a goose or moose, and raking leaves into its mouth from a mangrove forest like a ground sloth."

To better understand the dietary evolution of theropods, the researchers studied information on 75 other species within this group. They determined therizinosaurs experienced an early evolutionary split from the Maniraptora, which includes modern birds and their closest extinct relatives. One such relative was Velociraptor, a carnivore that probably kicked prey to death with its large hind foot claws.

The new Utah dinosaur therefore suggests that "iconic predators like Velociraptor, one of the dinosaurian villains in the movie 'Jurassic Park' — may have evolved from less fearsome plant-eating ancestors," according to the scientists.

Since the very meat-loving Velociraptor emerged some 20 million years after plant-chomping Nothronychus graffami, it's now thought that some dinosaurs might have first been carnivores that evolved into omnivores or herbivores, which re-evolved back into meat-eaters.

Paleontologists aren't sure why some dinosaur lineages may have see-sawed back and forth with their diets.

"Our current thoughts are that in gaining the ability to eat more than just meat, maniraptorans may have been able to invade new niches in the ecosystem that were unavailable to them before," Zanno said. "In other words, they may have been able to find a new way of living in the ecosystem and new resources to exploit that gave them an advantage and allowed them to diversify into new forms."

Aside from what it reveals about dinosaur diets, the new Utah species is significant because of where it was found: in marine sediments that would have been between 60 and 100 miles away from the closest shoreline. The ancient sea is now part of a desert. Merle Graffam, a member of the excavation team, found the dinosaur while searching for sea-dwelling animals. The dinosaur was named after him.

"A big mystery is how this animal — either alive or as a carcass — could get so far out to sea without being torn apart by predators and scavengers," Gillette said. "This ecosystem had at least five species of plesiosaurs and many sharks and predatory, scavenging fish."

He added, "Maybe (the dinosaur) was stranded at sea and struggled for a few days before drowning and sinking to the bottom."

Paul Heinrich, a research associate at the Louisiana Geological Survey, offers another explanation. He thinks such complete dinosaur skeletons recovered in seaways may have rafted out to open water on "floating islands" after storms.

The recovered Utah dinosaur's remains are now on public display at the Museum of Northern Arizona. The exhibit, Therizinosaur: Mystery of the Sickle-Claw Dinosaur, will close in September before moving to the Arizona Museum of Natural History in Mesa.