Neil Armstrong moved slowly down the ladder. Getting to the moon had been a long time coming. He was an Ohio pilot who came from the same soil as Orville and Wilbur, who ejected from a crippled jet fighter over Korea just after turning 21, who flew seven test flights in the X-15 rocket, who saved himself and a crewmate in Gemini 8, who ejected from a lunar landing trainer a split second before it crashed.

In the 1950s and '60s, he flew about every propeller, jet, rocket and helicopter built by his country. To say that this Midwestern farmboy was the best test pilot in an emergency ever was an easy argument. That’s why chief astronaut Deke Slayton chose Neil Armstrong to take the first step on a small world that had never been touched by life. A landscape where no leaf had ever drifted, no insect had ever scurried, where no blade of green ever waved, where in the silence of vacuum even the fury of a thermonuclear blast would sound no louder than a falling snowflake.

More than 200,000 miles away, billions of eyes stared at the black-and-white TV picture. They watched Neil’s ghostly figure move like a spacesuited phantom, closer and closer, planting his boots in moondust at 10:56 p.m. ET, July 20, 1969.

All motion stopped. "That's one small step for a man," Neil said slowly, "one giant leap for mankind."

Neil gathered several ounces of rock and soil from the lunar surface and stuffed the invaluable material in a suit pocket. The plan was, after Buzz Aldrin joined him, they would remain outside for two hours, planting experiments and collecting primarily rocks, but if something should go wrong, at least they would have a tiny bit of the moon.

With the contingency sample safely tucked away, he took the time to look around. “The moon has a very stark beauty all its own,” he said, almost whispering. “It’s like much of the high desert areas of the United States. It’s different, but it’s pretty out here.”

What we on Earth did not know at the time was exactly whyhistory’s first moonwalk began when it did. NASA had scheduled a four-hour sleep and rest period for Armstrong and Aldrin in the lunar module, or LM, and we were told to wait.

It turned out that we were hoodwinked.

The truth came out last November. NBC News President Steve Capus was giving me a dinner to celebrate my 50 years at the network. Former astronauts Neil Armstrong, John Glenn and Edgar Mitchell flew in, along with other survivors of the old days. Following dinner and a short ride to one of our favorite watering holes, Neil spilled the beans.

“Of course we wanted to get outside as soon as possible, before an emergency. But we thought we would need several hours to get the LM’s fluids and systems settled,” he explained.

"For several hours you reporters would have been speculating, guessing about possible problems, and we didn’t want one of you inventing stories,” Neil grinned. “That’s why we put in a four-hour sleep and rest period we hoped we would never use.”

We laughed, and Neil laughed, and he added, “Everything went much faster than we expected.”

Most of us were having dinner when the call came that the moonwalk would begin early. We rushed back to our microphones and reported the history-making event of our lives.

Buzz takes his turn

While Neil took his one small step, Buzz Aldrin stayed aboard the lunar module, which they named Eagle, to monitor its systems. That was his duty as lunar module pilot, and that was one reason why he was the second man to walk on the moon. When he and Mission Control were convinced that the Eaglewas safe and purring, he joined Neil on the surface.

“Beautiful, beautiful! Magnificent desolation,” Buzz said as he stared at a sky that was the darkest of blacks above a landscape that was many shades of gray, a touch of brown, and utter black where the rocks cast their shadows. No real color, not even the places lit by the unfiltered sun.

Then there was the weak gravity. They weighed only one-sixth of their Earth poundage, and Neil reported, “The surface is fine and powdery. It adheres in fine layers, like powdered charcoal, to the soles and sides of my boots. I only go in a fraction of an inch, maybe an eighth of an inch, but I can see the footprints of my boots and the treads in the fine, sandy particles.”

Was the moonwalk faked? No!

It would be these highly defined footprints that would set some armchair physicists crying the moonwalk was a fake. In the years to come there would be those who would claim Apollo astronauts never went to the moon. They said all of it was done on a movie set in an Arizona.

It occurred to me that if NASA had been so deviously smart to persuade 400,000 Apollo workers to lie, to persuade the Russians to lie, to persuade the people tracking the lunar flights with giant radio antennas around the world to lie ... well, if NASA got away with it once, would the agency be so stupid as to try to get away with this world-class hoax nine times?

The claim is too dumb not to be laughable. It is sad. We as a people would rather think the worst of ourselves than the best.

Nevertheless, scientific investigators investigated.

Myth-believers claimed that Neil and Buzz could have only left such firm, defined bootprints in soil with moisture — and everyone knows there is no water on the moon, right?

Wrong. There’s now evidence there could be water ice at the poles, but that hasn’t a thing to do with the first footprints on the moon.

Close examination of the lunar soil back on earth showed it to be virgin. The grains still had their sharp edges. They had not been rounded off by wind and erosion in an atmosphere. In their vacuum the sharp edges of lunar soil cling together, leaving a smooth surface much as moist sand does on a beach.

"Where were the stars," the myth-believers ask. "Where’s the crater carved out by Eagle'sdescent rockets during landing?"

The cameras that NASA sent to the moon had to use short-exposure times to take pictures of the bright lunar surface and the moonwalkers' white spacesuits. Stars’ images were too faint and underexposed to be seen, as they are in photographs taken from Earth orbit. And why didn’t the descent rockets carve out a crater? Their thrust was simply too weak to make a huge dent in the lunar surface.

So much to see, so little time

For Neil and Buzz there was so much to see and do and so little time. They moved their television camera 60 feet from Eagle. This would help Earth’s viewers see some of the things they were seeing and let them watch them going about the business of setting up Apollo 11’s experiments.

The two had problems jamming the pole that held the American flag into the lunar surface. Though a metal rod held the flag extended, the subsurface soil was so hard that they had to bang and push on the pole to get it to barely remain erect. Their forcible actions left the flag’s staff rocking back and forth for an unusual length of time.

Ah, said the myth-believers. That’s wind blowing the flag, and everyone knows there’s no wind on the moon. Right?

Right, there’s no wind on the moon. No atmosphere, just vacuum. And everyone knows an object that is forced into repeating motions in vacuum repeats many more times than it does in atmosphere. Atmospheric drag dampens movement. Vacuum is nothing. No resistance.

The flag’s motion was later duplicated in a vacuum chamber at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

No fraud, no conspiracy.

With Old Glory standing, Neil moved off to take more pictures while Buzz set up a seismometer to gather information on quakes and meteorites hitting the moon. An instrument to measure the flow of radiation particles inside the solar wind and a multi-mirror target for returning laser beams fired from Earth were deployed — laser reflectors that have been used by American universities and Russian institutes and other global investigators to determine the distance between Earth and the moon to the inch.

Those laser reflectors could not have been used if Neil and Buzz had not put them there.

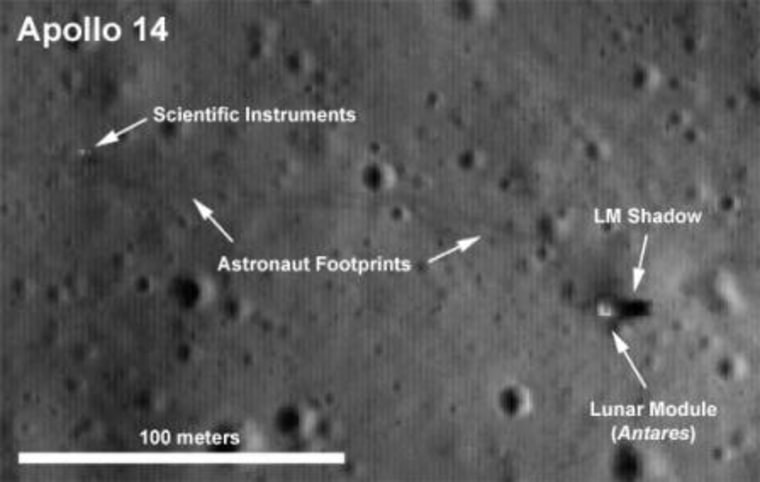

Just days ago, NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, launched last month from Cape Canaveral, returned its first images of the Apollo moon landing sites. The pictures show five of the six Apollo descent stages, including Apollo 11's, resting on the moon's surface. The Apollo 14 landing area shows a faint trail of Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell's two-mile round-trip march to Cone Crater with their "rickshaw."

Guess we really did go to the moon, huh? So much for the myth-believers and the conspiracy theorists.

In the lunar dust, the two Americans placed mementos for the five astronauts and cosmonauts who had lost their lives, and Neil read the words on a plaque mounted on Eagle's descent stage: “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the moon, July 1969, A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.”

Neil and Buzz gathered about 46 pounds of lunar materials, and once everything was loaded for flight back to Earth, they shut down the first moonwalk.

Was Buzz Aldrin a publicity hog? No!

Because of the primitive state of television at the time, most of us couldn’t wait for Apollo 11 to get back with all the great pictures the crew had shot. That in itself was the beginning of yet another controversy.

When all the film had been developed, there was only one image out of the 121 Hasselblad still-camera photographs that showed Neil on the moon, plus the film from a 16mm movie camera that was set up to peer out one of Eagle's windows. Neil had taken great shots of Buzz moving about, Aldrin took only one rear shot of Neil stowing samples for return to Earth.

Why?

Was Buzz angry?

No.

“I was the one with the camera,” Neil told me. “His job was to set up the experiments. He had much to do. Nothing more than that.”

Two months ago I had the same conversation with Buzz, and got a similar response. “NASA should have trained us in public relations,” he said with passion. “We were just doing our job.”

Simply put, MIT-educated Buzz Aldrin was one of the smartest guys in the astronaut corps.

During Project Gemini, spacewalker after spacewalker had failed. They tired quickly, and Buzz studied their problems. By the time he stepped into space, he had invented the tools and methods needed to walk in a vacuum. For example, he fashioned a pair of golden slippers that could be placed where needed to hold his booted feet. A spacewalker needs that — something to hold his or her feet in place — to keep stable attachment with the spaceship. Otherwise you will thrash about wildly. During Gemini 12, Buzz Aldrin whistled and sang through his spacewalk assignments.

And when he returned from the moon, when one of those moon-conspiracy theorists shoved a Bible in Aldrin’s face and ordered him to swear on it that he walked on the moon, Buzz decked him. Fellow astronaut Wally Schirra, one of the original Mercury 7, renamed him Rocky. That’s my kind of man.

After 51 years on the job, after covering every spaceflight flown by Americans, I can report that Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin — and Michael Collins, who kept stoking the home fires on board the Apollo 11’s command ship Columbia — were the best Earth had to offer.

History, this time we got it right.