Imagine having a nice ripe orange, ready for squeezing, but being able to get out only a small amount of juice. There's got to be more, you just can't get at it.

That's the frustration of the global oil business.

The industry is spending billions on technology to increase the amount of oil it can extract from the ground. Oil companies typically recover only about one in three barrels of oil from their fields, but they can't afford to leave so much crude untapped at a time when it's difficult to access new reserves. Recovering more oil has enormous implications, not only for the companies' balance sheets but also for the world's diminishing supply.

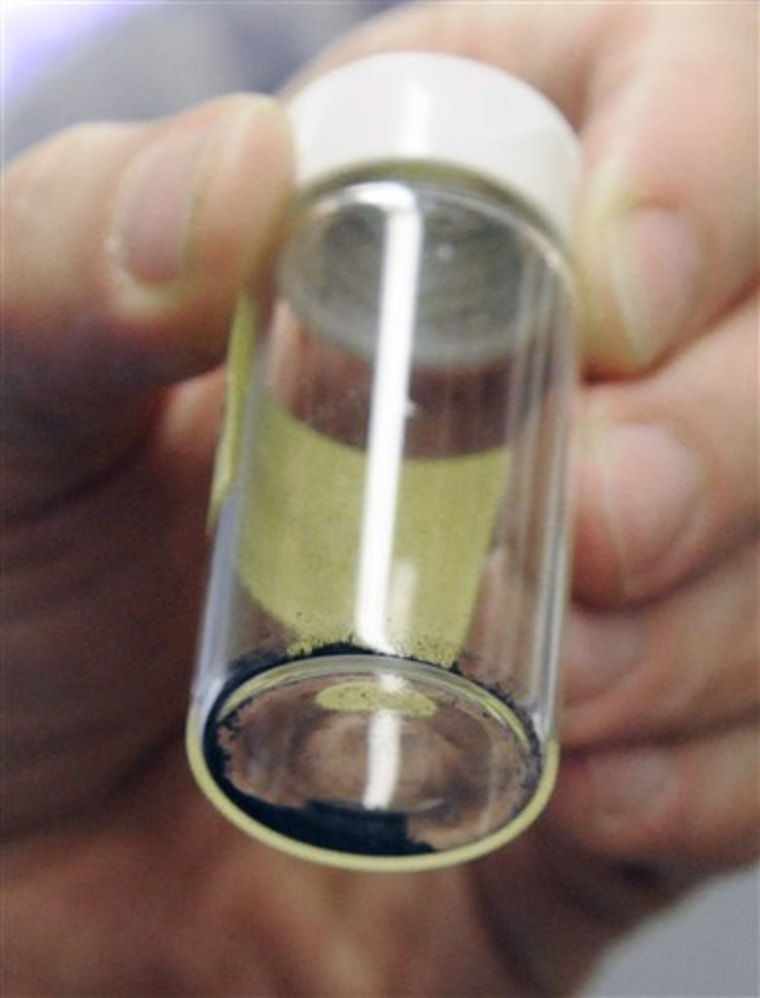

One of the latest attempts to learn where the oil is hiding would involve injecting hundreds of millions of tiny carbon clusters deep into natural underground reservoirs, where changes to their chemical makeup would signal whether they've come across oil, water or other substances.

The clusters, referred to as "nanoreporters" and roughly 30,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair, also can tell the temperature, pressure and other factors that can help a company zero in on more oil.

Major oil companies, including Royal Dutch Shell, BP, ConocoPhillips and Marathon, are funding the research at Rice University. Scientists at Rice say they hope to begin field tests in the next year.

Upgrading techniques

The industry is also upgrading the ways it plies more oil out of the earth, techniques that involve heat and chemical injections or gas and water pressure. These methods account for 3 percent of world oil production, according to the International Energy Agency, the Paris-based policy adviser to 28 countries.

If oil companies could recover 50 percent of the crude in their fields instead of 35 percent, it would double the world's proven reserves of about 1.2 trillion barrels, the IEA says.

Though it could take a couple of decades to reach 50 percent, even a modest increase in the amount of oil recovered in coming years will alter the debate about peak oil — the point at which half the world's reserves have been depleted.

The debate pits those who say there's enough oil to last a hundred years or more against those who see a looming scramble for a shrinking supply. The latter group foresees supply shortages and price spikes that could cripple the global economy.

Nansen Saleri, the former head of reservoir management for Aramco, Saudi Arabia's national oil company, said improving worldwide recovery rates by 10 to 15 percent could provide an additional 50-year supply of oil at current consumption rates.

"I'd say 15 to 20 percent (recovery) is doable, especially if you assume we're going to be in a robust price environment," said Saleri, whose Houston-based consulting business, Quantum Reservoir Impact, helps producers improve recoveries.

Little secret agents

The key is obtaining detailed information about what's going on thousands of feet below the earth's surface. That knowledge can improve the odds of drilling accurately and cut down on costs. The industry has made significant advances in seismic testing and other imaging and sensing technology, but reservoirs remain, in many ways, deep, dark mysteries.

As they're pumped with water through a reservoir's nooks and crannies, the molecular makeup of the Rice University nanoreporters is designed to change depending on what they encounter — petroleum, hydrogen sulfide, other substances.

The nanoreporters have tags similar to bar codes on retail packages that will tell scientists how long they've been underground — three months, six months, nine months, longer. Companies can then pinpoint where oil might be trapped. For example, if a large number of nine-month nanoreporters come across oil while three-month nanoreporters don't, scientists can assume the crude is deeper in the reservoir.

Lead scientist Jim Tour likens the nanoreporters to secret agents because they're able to infiltrate tiny pores in the reservoir and gather important information.

Besides the research at Rice, Royal Dutch Shell is doing its own work on oil-seeking nano-particles. Shell scientist Sergio Kapusta said the research is several years from being ready for application, but the "smart" particles eventually could be used to relay real-time information from within the reservoir.

"Getting those 'secret agents' out and interrogating them is one approach," Kapusta said. "What would be great is if (we) could figure out a way to interrogate them even while they're behind enemy lines."

Promising but untested

Nanotechnology is a promising but untested tool for discovering oil, said Albert Yost, a manager at the National Energy Technology Laboratory in Morgantown, West Virginia, who is familiar with the work at Rice.

"The question is can (the nanoreporters) be used routinely to tell you what's going on" in the reservoir, said Yost, whose lab is owned by the Energy Department.

Attempting to squeeze more oil from the ground has been the chief goal of crude hunters since "Colonel" Edwin L. Drake struck it big in 1859, employing the skills of salt drillers to create the world's first oil derrick in the tiny, impoverished town of Titusville, Pennsylvania.

These days, some companies inject heat or chemicals to reduce the viscosity of oil so it can flow more easily from the reservoir; others rely on pressure from water or gases to force crude out of the complex, geologic formations. One or more of these procedures could be used to extract the oil discovered by the nanoreporters.

Costs to extract extra oil vary between $10 and $80 a barrel, depending on the method, the IEA estimates. Oil is now trading around $65 a barrel, making some of the costlier recovery not feasible.

The nanoreporter research is funded by a multimillion-dollar consortium made up of oil industry companies. They're willing to spend on a technology that could unlock billions in profits.

Increasing output is especially important for big companies like Exxon Mobil and BP as they find it harder to secure new sources of fossil fuels. Most of the world's proven reserves — about 80 percent — are held by national, state-run companies like those in Venezuela and Saudi Arabia.

BP says advancements in technology — including gas injection — will likely allow it to recover 60 percent of the oil at its massive Prudhoe Bay field in Alaska. The original estimate three decades ago was 40 percent.