The civilian Blackhawk helicopters deployed in January to help defend the skies over the nation’s capital are on round-the-clock alert in the wake of an MSNBC.com story that described how the choppers were only providing partial daily coverage.

Such 24-7 coverage had typically been reserved for times of terrorism high alerts. Prior to the MSNBC.com story, the Blackhawks patrolled Washington airspace only 16 hours a day as part of the region’s so-called “layered” air defense that provides round-the-clock coverage by using military aircraft and mobile surface-to-air missile units.

The decision to fly around the clock was made at a meeting a day after MSNBC.com revealed that the Blackhawks were providing only partial coverage because of a lack of funding and limited resources, according to sources familiar with the meeting.

Before MSNBC.com’s story, Charles Stallworth, commander of the unit housing the Blackhawks said, “If it were published [that the helicopters only are on alert 16 hours a day], I’d be seven-by-24 within 24 [hours] of that.”

Greater impact

“And that would have a greater impact on my people and missions that were out there, but I’d have to do that,” said Stallworth, director of the Office of Air and Marine Operations, in a previous interview.

Stallworth declined a request for a second interview. A spokesman for AMO would neither confirm nor deny the move to round-the-clock coverage by the Blackhawks. “As we previously told you, there has been 24/7 coverage over the national capitol region by a variety of agencies and that continues at this time,” said Dean Boyd, a spokesman for Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the unit that houses AMO. “Any other operational details I cannot discuss with you in any way, given the obvious sensitivities.”

The Blackhawks aren’t stationed in Washington on a permanent basis. In practical terms, that means both equipment and crew members must be pulled from normal assignments; although the helicopters remain parked at Reagan National Airport, their crews rotate in and out. This cannibalizes the mission in the field, often leaving those operations shorthanded and unable to fly missions that otherwise would be flown.

'Share the pain'

“Yes, the mission [in Washington] has an impact our other missions,” Stallworth previously told MSNBC.com. “But all in all, we try and share the pain so that we don’t do permanent damage to any of our local operations.”

The two Blackhawk crews currently in Washington to cover the mission are pulling 12-hour shifts. It isn’t clear if a third crew will be pulled from the field at a later time to provide for traditional eight-hour shifts. That move would further strain the capabilities of the Blackhawks in the field.

The Blackhawks in Washington — two of only 16 in civilian use and operated by AMO — are traditionally used to combat airborne drug smuggling while providing surveillance for local, state and federal law enforcement investigations, including anti-terrorism missions in the post 9/11 era.

AMO has a budget request pending that would make Washington a permanent assignment and provide additional resources for the Blackhawk field offices, but the outcome of such a request is uncertain and Stallworth, in his prior interview, refused to handicap the chances of his request receiving approval.

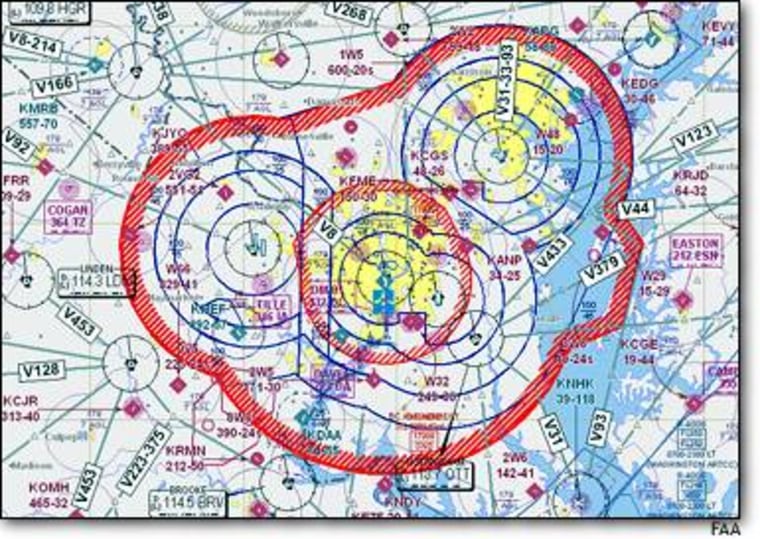

The Blackhawks help protect a 23-mile lopsided ring of restricted airspace around the Washington D.C. region known as the Air Defense Identification Zone. Within that ring is a 15-mile strict no-fly zone known as the Flight Restricted Zone (FRZ) that protects the White House and Capitol Hill.

'Squawk' codes

Air traffic controllers from the FAA constantly monitor the ADIZ. They assign “squawk” codes to each plane flying inside or coming into the ADIZ.

If a plane “punches the bubble” of the ADIZ without that code, they are flagged as a violator; there have been 610 such violations of the ADIZ since it was officially established in February. The Blackhawks can launch to determine if a violator is simply lost or has a more nefarious mission in mind.

In the six months before the Blackhawk deployment in Washington, there were 186 intrusions into FRZ. Since the Blackhawks arrived, that number has been cut to 15, Stallworth said in his previous interview.

But some question whether the Blackhawks are needed at all. At the very least, questions about administration of the ADIZ are giving rise to questions about the entire air security complex that has grown up around the capital area.

“We understand the need for security and we at least accept the FRZ,” said Warren Morningstar, spokesman for the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association. “But the ADIZ itself has turned out to be an operational disaster,” Morningstar said. “The question is, really, how effective is it as a security measure?”

Morningstar said that creating the ADIZ “doubled the airspace” that FAA air traffic controllers had to deal with without providing the resources to better manage that responsibility.

'Endlessly' circling

At times, pilots are stuck on the ground trying to get clearance to fly inside the ADIZ or are made to simply circle “endlessly” in the air at the fringe of the ADIZ “trying to get clearances to enter the ADIZ,” Morningstar said.

And all that just increases the chances of a violation happening, Morningstar said. His group has documented cases of pilots mistakenly being told to fly into the FRZ. In other cases, pilots were cited for having violated the ADIZ when no actual violation took place, Morningstar said.

“I’m not denying that someone could do some damage with a [general aviation] airplane,” Morningstar said. “But is the potential for that damage and the potential for that risk so great as to require all the procedures that we’ve put into place right now in the Washington area? We’re not convinced that it is,” he said.

Nowhere in the world has a small private plane been used as an instrument of terrorism, Morningstar said. “I have to believe that the reason is that there are easier ways of making a bigger statement than you can do with a small airplane.”