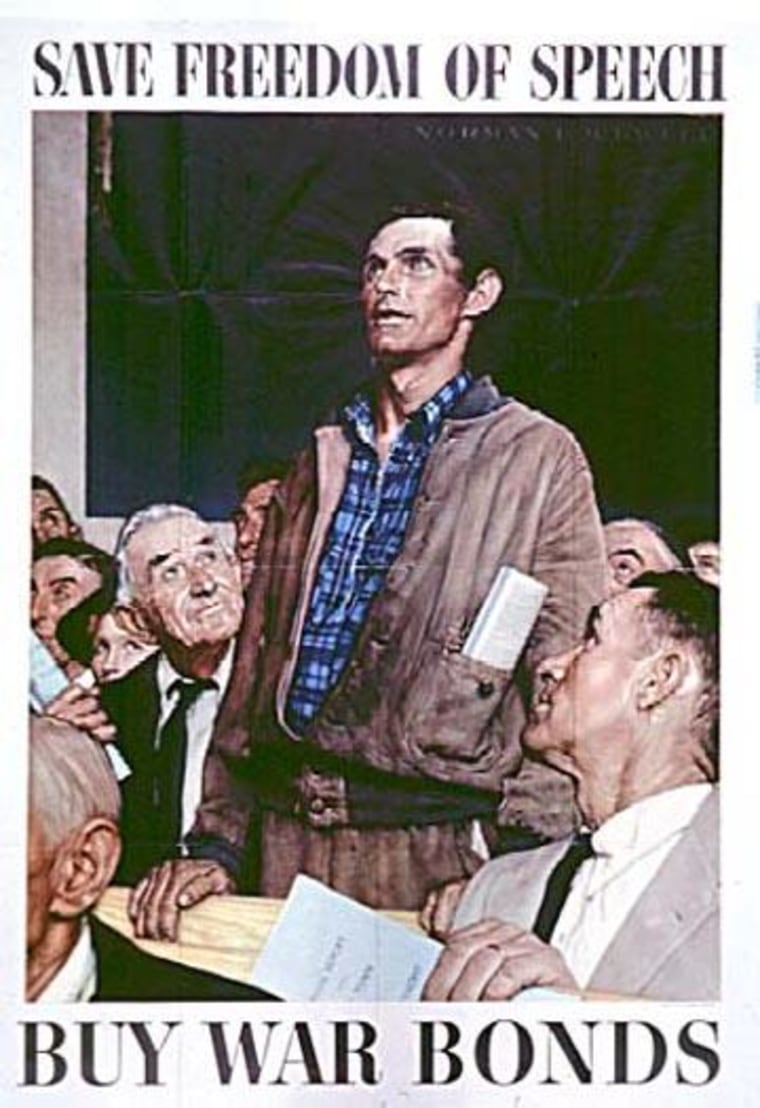

A working man rises from his seat to make his voice heard at a town meeting. His stance is firm, his grip on the rail before him and the rolled-up agenda in his pocket tell us he has decided he has the same right to address the gathering as the better-off businessmen looking on, their ties still cinched after a day spent at the office. He is of a different class, and yet every bit a member of the same community, and so his words are every bit as important.

People gather in prayer. While we're not let in on the specific event—and its ephemeral casting—the use of light and space by the artist lead us to believe its a figurative gathering— the message is stark. The participants are of diverse beliefs. The accoutrements of their varied religions tell us as much. Yet they gather as a group, under one roof, with a single aim.

A family has gathered on Thanksgiving Day. The sunny, scrubbed, cherubic faces of family members form an idyllic human frame around the scene: the great fanfare greeting the arrival of the bird, cooked to a perfect golden brown, in the capable hands of the apron-wearing grandmother, standing alongside the matriarch, at a time when we still dressed that way for dinner. The joy of the assemblage is as palpable as the implied message is powerful: this is the land of plenty. This is the domestic American ideal. This is what our boys are fighting for.

And so is this: the scene is an upstairs bedroom in the evening. A father, just north of fighting age himself, clutches a newspaper telling us of the ongoing horrors overseas. His wife lovingly tends to the sleeping children in their shared bed, living emblems of the safety of the American home and way of life. They simply cannot know of the titanic struggle being fought on the beaches of the South Pacific and the frozen forests of Europe.

The Four Freedoms—freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from want, freedom from fear—were first laid out by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in his 1941 State of the Union Address. Two years later, they were put to canvas—depicted by Norman Rockwell in four successive issues of the Saturday Evening Post.

While the speech that motivated these four works—along with the paintings themselves— would likely reflect a different reality today (Roosevelt's call for worship of the "God" of our choice, the lack of racially diverse faces at the American Thanksgiving table, and the role of women in the home), the freedoms that Rockwell depicts remain as four fixed stars in our collective national constellation. We debate these freedoms, we protest when we fear they are being diminished, and we send young volunteers half a world away to fight for their preservation.

That the foremost visual artist of his time participated in the War Bond movement meant the world to the war effort overseas. When the four paintings went on tour, the national campaign raised an estimated $130,000,000 for bombs and bullets and ships and planes. The role of the Saturday Evening Post in American life during the 1940s is hard to comprehend in the television and internet era, but its delivery in millions of American households was a widely anticipated weekly event.

It is difficult today to express or imagine the tactile thrill that the magazine gave its readers, and it started with the cover -- during the war years alone, 33 of them were the work of Norman Rockwell. It remained on household display for a week at a time, face up, a coffee table staple in living rooms across the country, where the cover image so often matched the message delivered over the radio by our President—as artful in his use of the spoken word as the great Norman Rockwell was with a brush in his hand.

Effete critics will go on debating Rockwell's art. Others will insist that Rockwell was painting an ideal instead of reflecting a reality. Rockwell himself knew America was all about ideals. He saw his own task through his steady, exacting lens: to remind us who we are, and what we aspire to be. That was... and is... Rockwell's America.

Editor's Note: The above article originally appeared in the book “In Search of Norman Rockwell’s America” by Kevin Rivoli, published by Howard Books (October 21, 2008).