As counselor Sherry Lynch Conrad bid goodbye to Seung-Hui Cho after a 45-minute session, she urged him to return in January. He never made an appointment.

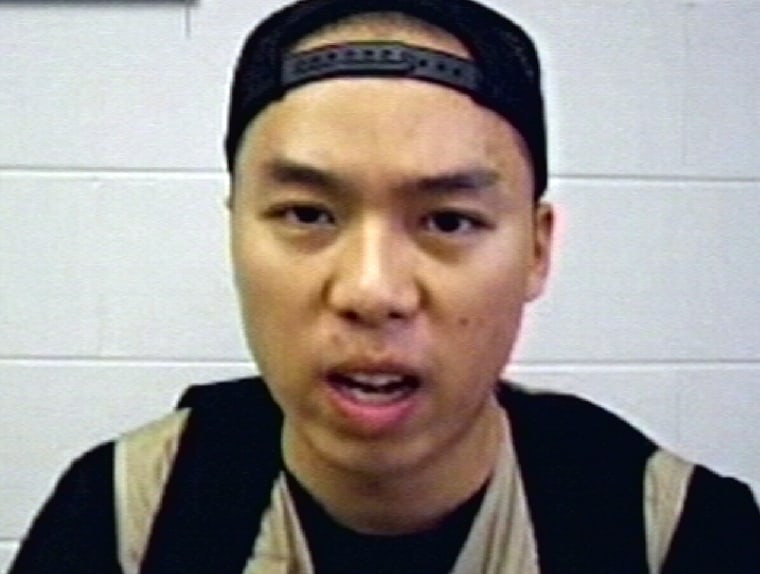

That single in-person meeting in December 2005, which followed two telephone triage sessions, was the last contact Cho would have with therapists at Virginia Tech's campus counseling center. Sixteen months later, he killed 32 people and himself in the worst mass shooting in modern U.S. history.

Could Conrad and her colleagues at Cook Counseling Center have done more to prevent the massacre?

The families of two of Cho's victims, who have sued the state and the school seeking $10 million, certainly think so. But some experts who reviewed Cho's recently discovered mental health files aren't so sure. They say the treatment the Virginia Tech gunman received at Cook was typical of that given to students in similar circumstances who appeared to pose no imminent danger.

"These look like thousands and thousands of records I've seen before," said Gregory Eells, director of Cornell University's counseling services and president of the Association for University and Counseling Center Directors, who reviewed the records after they were released Wednesday. "They were asking the right questions."

Eells and other experts say the fact that a student like Cho could conceal his problems from counselors reflects the increasing complexity of mental disorders such centers around the country are facing.

Counselors face 'complicated cases'

Anxieties over grades, college romances and homesickness are still mainstays on American campuses, but counseling centers have had to adapt to a growing number of more troubled individuals.

People with mental disorders are being treated at a younger age, meaning more students are arriving on campus with deeply rooted problems that might have prevented them from going to college at all a generation ago, Eells said.

"We see some pretty complicated cases," said Eells.

In response, centers have stepped up training requirements for their staffs of psychiatrists, licensed psychologists and clinical social workers. Conrad, a psychologist, had a doctorate.

Still, school counseling centers typically are equipped to give brief treatment and then refer more serious cases to another mental health agency. And they are only equipped to treat clients who come in voluntarily.

"We really cannot collar a student and drag them in for services," said Dennis Heitzmann, director of Penn State's Center for Counseling and Psychological Services.

Cho had contact with the counseling center at the university in Blacksburg three times in a two-week period. The sessions came after female students complained to police about Cho's disturbing behavior.

There were the two telephone sessions, and the one in-person session with Conrad after Cho had spent the night in a mental hospital because he expressed suicidal thoughts to a roommate.

In all three sessions, he admitted being depressed and anxious, but denied any homicidal or suicidal thoughts.

"It appeared to be a situation that didn't suggest any imminent risk to himself or others," said Heitzmann, Penn State's director for 25 years and a former president of the counseling directors' association.

But relatives of Cho's victims have said there were numerous red flags — that the counseling center should have done more to ensure that Cho didn't fall through the cracks.

"It just sounded like he was going through a McDonald's," said Michael Pohle, whose son Michael Pohle Jr. was killed. "It just looked like he was passed through from one person to another person and there was no collaboration going on."

It's true that Cho was counseled by three different Cook staff members, but Heitzmann said that's normal for triage sessions.

"It isn't necessarily that he fell through the cracks," he said. "It's more like he found the cracks and hid in them."

Psychologist Neil Bernstein, who has a private practice in Washington, D.C., said the responsibility for recognizing problem students shouldn't lie solely with campus counselors.

"This kid was around lord knows how many students and teachers," he said. "What did they do? What does it say about our country? What does it say about the mental health stigma? There's that fear of being wrong."

Privacy laws hid some information

There was also information the Cook counselors didn't have, including information on treatment he received in middle and high school that was protected by privacy laws.

Cho was diagnosed with a social disorder called "selective mutism," the summer before he entered seventh grade, according to a report on the Virginia Tech shootings by a governor-appointed panel. He'd had a psychiatric evaluation in the eighth grade after expressing homicidal and suicidal thoughts, and he received therapy through much of high school.

Nor was there any mention in his file that the director had discussed Cho with the head of the English department when his violent writings and bizarre behavior scared students and his professor.

Heitzmann said counseling centers deal with hundreds of clients a year and "it's conceivable that an individual may not be on a director's radar screen."

There was other information that might have set off alarm bells, but didn't reach the Cook counselors in time.

Cook Counseling Director Robert C. Miller forwarded an e-mail to his staff from the Residence Life chief outlining Cho's erratic behavior. They received it right after Cho's only in-person session had ended.

Miller found Cho's missing records at his home last month, inside a manila folder with personal items he taken with him when he was removed as Cook's director in February 2006.

That is the unusual thing about Cho's records, said Eells, who could think of no reason a director would even keep the records on his desk.

"I think the most atypical piece," he said, "is that the former counseling center director had them in his house."