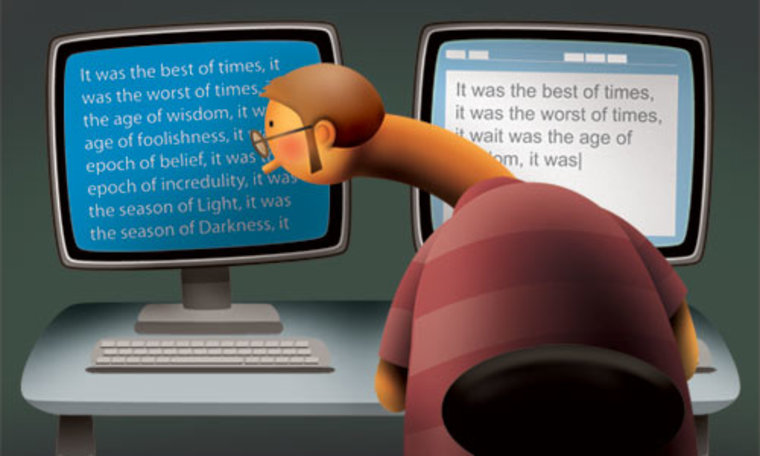

They scour the Web in search of stolen phrases, dig through documents looking for evidence of looting. They can’t issue citations, but they can certainly let you know if you’ve failed to include one.

Yes, the plagiarism police are on the job.

The practice of copying, imitating or blatantly stealing the original work and/or ideas of others is, to borrow a phrase, as popular as sliced bread, according to statistics compiled by Plagiarism.org. In fact, in a study of 4,500 high school students and 1,800 college students, more than half admitted to copying work from the Web without proper attribution.

Plagiarism has reared its ugly (and sometimes false) head in publishing as well, with accusations lobbed at everyone from the Bard of Avon to the queen of daytime TV.

In the last few months alone, the p-word has been tossed — rightly or wrongly — at New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd, Twilight author Stephenie Meyer, a consortium of Bollywood movie producers and some sperm researchers from Newcastle University in England.

The practice has even cropped up on 140-character microblogging site Twitter, with some users crying foul over blatantly copied and unattributed tweets.

“The Web has made it almost ridiculously easy to plagiarize,” says Patricia Wallace, psychologist and senior director of information technology at Johns Hopkins University Center for Talented Youth. “But it’s another one of these cat-and-mouse things. It’s made it very easy to do and now it’s easy to catch them.”

Copy-and-paste nation

One of the biggest players in online plagiarism programs is iParadigms, which offers three commercial services including Turnitin, a popular program used by around 8,000 educational institutes; WriteCheck, a “learning tool” designed for students to catch their own unintentional plagiarism and iThenticate, a program used primarily by corporations, law firms, research facilities, and scientific, medical and technical publishers (commercial publishers such as HarperCollins and Penguin have recently expressed interest, as well).

While a variety of packages are available, pricing for Turnitin generally ranges between $1 and $2 per student per year (there’s also a site license fee). WriteCheck charges $4.95 per 5,000 words and iThenticate offers customized pricing that depends on the type of customer, the intended use, and the expected volume.

Some people do intentionally co-opt intellectual property, but plagiarism mostly happens because people just don’t know any better, says Katie Povejsil, vice president of marketing at iParadigms.

“There are certainly people with malicious intent, but there are a tremendous number of cases that are in the middle area between complete ignorance and complete deliberateness,” she says.

“People do tend to go on the Web and grab something and use it and then forget that it’s not theirs. Or they just don’t understand the classic rules of the road about how you use and reuse material that’s available on the Web. They’re like, ‘Oh, it’s out there. I should be able to copy it.’ ”

'Eye-opening experience'

Janine Godwin, a certified professional organizer from Katy, Texas, says she started using the content-scanning program Copyscape in 2004 after she repeatedly found her work on other peoples’ sites.

“Talk about an eye-opening experience,” she says. “Other professional organizers had taken my writing and either put their name on it or put it on their Web site with my name on it but without permission. On one Web site, there were 860 words copied verbatim.”

Godwin currently runs her work through Copyscape’s free scanning program a couple of times a month but says she plans on subscribing to their premium service — which charges 5 cents a scan. According to Godwin, whenever she finds her work on other Web sites, she contacts the owners and asks them to remove it. If necessary, she brings in her lawyer to “scare the bejesus out of them.

“Nine times out of 10, they’ll be nice and take it down, but once in a while you’ll get somebody who’s a real butt,” she says. “They’ll either ignore it or be less than nice in their response. A lot of them say, ‘Oh, I just assumed it was okay to use because it’s online.’ ”

While accidental plagiarism happens both in and out of the academic realm, Ellen Lytle, a former graphic design and multimedia Web design professor at the Art Institute of Atlanta, says there are also those who beg, borrow or steal other people’s writing simply because they can.

“A lot of students figure nobody will find out, that the teachers aren’t smart enough to catch them,” she says. “It’s kind of pathetic that you have to doublecheck every kid, but that’s what I do.”

Lytle says she’ll either use Google to look up a “red flag” phrase — something that seems beyond the student’s normal writing ability — or enter the entire paper into Turnitin, which maintains a database of 11 billion Web pages, 90 million student papers, more than 12,000 newspaper, magazines and scholarly journals and thousands of books.

Sometimes, though, she doesn’t even have to do that.

“I had two students in the same class both download the official biography of Bill Gates off the Microsoft Web site and turn it in as their own,” she says.

“The first place I looked was the Microsoft Web site. They didn’t even change the wording.” (Msnbc.com is a joint venture of Microsoft and NBC Universal.)

Big Brother at work?

While Turnitin, Copyscape, Plagium (another free program currently in testing), and similar programs have many fans, there are those who point to their flaws.

“If you search the entire Internet you’re going to find something somewhere that says the same thing you said, even if you haven’t seen it before,” says Mathew Lederman, 21, an information sciences and technology and psychology student at Penn State University.

“There are only so many words in the English language that can be rearranged.”

Some educators also wonder whether these programs come off as a bit too Big Brother.

“In some cases, professors aren’t eager to use programs like this,” says Wallace, author of “The Psychology of the Internet."

“It’s like an electronic surveillance tool. It can be a valuable learning tool — plagiarism is so widespread and people don’t take it seriously enough. But in some ways, it can be a little like the red-light cameras, where you’re automatically guilty because the technology caught you.”

There’s even been a lawsuit (which iParadigms won in 2008) involving four high school students who claimed submitting their homework to TurnItIn was a violation of copyright law.

Today’s digital world presents new and difficult challenges, though, says Povejsil of iParadigms.

“There’s a whole new reality that the digital world has brought us to, and kids have a very different perception of things than the people who learned about fair use and plagiarism in a print world,” she says.

“One third of teenagers don’t believe that downloading a paper from the Internet is a serious offense. To them, copying text from a Web site is either a minor offense or it’s not cheating at all. That’s the world we find ourselves in and educators find themselves in.”

Street justice

And while there are those who would debate the ethics of the “plagiarism police,” few disagree that plagiarism is rampant. And that something needs to be done to prevent it, even if it’s a good old-fashioned public shaming.

“One of my friends found that someone on Twitter had copied her tweets and those of her friends,” says Risyiana Muthia, an editor from Jakarta, Indonesia, “Some of them were poems or very short stories but other tweets were trivial, like daily stuff or personal rants. She copied it word for word.”

The buddies did a bit of digging, posted a series of “twitter thief” warnings and outed the alleged “plagiator” by name. Shortly thereafter, the tweet stealing came to a screeching halt and the person’s Twitter page went dark.

“I’ve been the victim of plagiarism several times, on blogs or other spaces where I make my work publicly available,” says Muthia. “But I’ve never found any case of plagiarism on Twitter before. I hope she learned her lesson.”

Diane Mapes is a Seattle freelance writer and author of "How to Date in a Post-Dating World." She can be reached via her Web site, dianemapes.net.