All Ric O'Barry wants is to stop the dolphin killing, so the trainer for the 1960s "Flipper" TV series traveled to this seaside Japanese town, where the hunt goes down.

The American activist, who is the star of a new award-winning documentary that depicts the dolphin slaughter here, got an unwelcome reception when he showed up here this week for the start of the annual hunt.

As he roamed this village of 3,500 people, he talked to fishermen, Japanese reporters, police who questioned him — anyone who would listen to his message that the dolphins must be saved.

"We have to keep Taiji in the news," O'Barry said, bringing his own camera crew and a few foreign reporters on an impromptu tour by chartered bus. "There is an international tsunami of attention."

His movie, "The Cove," directed by National Geographic photographer Louie Psihoyos, was released in the United States a month ago but has yet to come out in Japan.

The film, which won this year's audience award at the Sundance Film Festival, juxtaposes stunning underwater shots of gliding dolphins with others from the hunt.

Its hero is O'Barry, still a weathered outdoorsman at 69, who, after training dolphins for the "Flipper," had a change of heart in 1970. He has devoted his recent years to helping return dolphins in captivity to the wild and to stopping the killing at Taiji.

Scenes in the film, some which were shot clandestinely, show fishermen banging on metal poles stuck in the water to create a wall of sound that scares the dolphins — which have supersensitive sonar — and sends them fleeing into a cove.

Market for dolphins

There, the fishermen sometimes pick a few to be sold for aquarium shows, for as much as $150,000. They kill the others, spearing the writhing animals repeatedly until the water turns red.

The meat from one dolphin fetches about 50,000 yen ($500), and is sold at supermarkets across Japan, where dolphin and whale meat are considered delicacies.

"I've been working with dolphins for most of my life. I watched them give birth. I've nursed them back to health," said O'Barry. "When I see what happens in this cove in Taiji, I want to do something about it."

Greenpeace and other groups have tried to stop the hunt for years. Activists hope "The Cove," which tells the story like a gripping detective movie, will bring the issue home to more people internationally — and eventually in Japan.

Already, the Australian town of Broome dropped its 28-year sister-city relationship with Taiji last month, partly because of the movie.

O'Barry's team is preparing an online version of "The Cove" in Japanese, as well as trying to find a theater distributor.

Most Japanese have never eaten dolphin and would likely be stunned by the slaughter portrayed in the movie.

The Japanese government, which allows a hunt of about 20,000 dolphins a year, argues that killing them and whales is no different from raising cows or pigs for slaughter. But conservationist groups, like Sea Shepherd, have dogged the Japanese whale hunt — which the government allows for academic research but from which the meat is also sold — chasing whaling vessels in an effort to impede their operations.

"People say dolphins are cute and smart, but some regions have a tradition of eating dolphin meat," said fisheries official Toshinori Uoya. "Dolphin killing may be negative for our international image, but it is not something we can order stopped."

In Taiji, the fishermen have long turned tight-lipped toward outsiders who question the hunt.

One blocked the door of a supermarket, preventing O'Barry's crew from buying bottled water there.

The town government in Taiji — which has made whales and dolphins its trademark, with dolphin shows, a whaling museum, whale-watching, whale-meat restaurants and whale-sausages on sale — refused to comment about "The Cove," or the growing international criticism against dolphin-killing.

Police question him

As soon as O'Barry arrived, he was stopped for questioning by several plainclothes police officers, who demanded his crew members show their passports.

One officer said "The Cove" included footage shot by trespassing. O'Barry said his team was challenging that allegation because the cordoned-off area was in a national park.

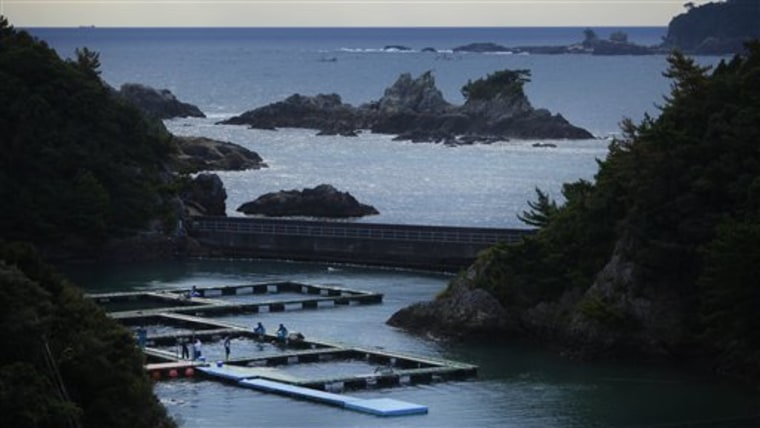

O'Barry drove around Taiji, getting his crew to take footage of the park overlooking the cove. Later, he described as "torture" the small tanks for Taiji's captive dolphins, all the while savoring the attention he was getting for his cause.

He was ecstatic the fishermen hadn't gone out to the cove, at least during the first days of his visit. "Today was a good day for dolphins," he said.

He also hopes that reports of high mercury levels in dolphin meat, which the Japanese government acknowledges, will convince Japanese to stop eating dolphins.

But many in Taiji take the dolphin hunt for granted as part of everyday life.

They are defensive about "The Cove," seeing themselves as powerless victims of overseas pressure to end a simple and honest way of making a living. About 20 to 30 fishermen earn money from the hunt, although they also catch fish.

"It tastes so good," Mutsuyo Kaino, an 88-year-old housekeeper, said of dolphin meat, which is eaten raw as sashimi or stewed in a pot. "This is a fishing town. You shouldn't worry about a movie."