Apophis is coming.

On April 13, 2029, an asteroid the size of two and a half football fields, a solid rock named for the Egyptian god of evil and destruction, will come out of the heavens moving at 4 miles per second (6.4 kilometers per second), streaking as close as 18,300 miles (29,300 kilometers). That's closer than the geosynchronous satellites orbiting Earth.

Some will watch in wonder. Others will pray. A few will study and marvel at the bright object moving so close over our shores. But most will stand stunned, witnessing the closest celestial threat to our planet in our lifetime. If our luck should fail, if some force should change the asteroid's path ever so slightly, Apophis could turn an area the size of the state of New York into an instantaneous hell.

If Apophis hits — either in 2029 or during a follow-up encounter in 2036 — the sheer violence of the 900-foot-wide (270-meter-wide) rock would throw billions of tons of scorched earth and vaporized water and melting metals and glass into the atmosphere. The sun would be blotted out in the blast zone. Living things would be wiped out.

Scientists are still weighing how much of a threat Apophis actually poses. After five years of carefully calculating Apophis' path, NASA this month reduced the probability of a direct hit from a 1-in-45,000 chance to 1-in-250,000.

"I believe Apophis will miss," David Morrison, a NASA researcher specializing in asteroids and comet impact hazards, told me. "But what we really need to know is its exact orbit so we can be sure it will miss us not only in 2029 but on its return in 2036."

Morrison would like to place a transponder for precise measurements on the asteroid long before it makes its flyby.

Why so early?

Because if NASA needs to redirect Apophis, a single rocket can do the job before it arrives.

Asteroids on the radar screen

Just last week an independent panel released a report reviewing America's future in space, and near-Earth asteroids and comets were listed among suggested targets for exploration. Now it's up to President Barack Obama to turn the panel's findings into policy. Many astronomers and scientists are hopeful he will recognize the threats that near-Earth objects pose.

Slideshow 12 photos

Month in Space: January 2014

The impact threat gained fresh prominence in July when the planet Jupiter took a noticeable cosmic hit for the second time in 15 years.

In 1994, Comet Shoemaker-Levy became a star attraction when it hurtled into Jupiter's oceans of gas. The giant planet's gravity tore the comet into a long strand of individual rocky chunks, a glowing "string of pearls," and on July 21 of that year, scientists had their first-ever opportunity to watch one orbiting body slam into another.

The string of comet chunks set off an unprecedented fireworks display. Fireballs erupted on Jupiter as the huge rocks ignited almost instantly, due to friction with the upper clouds of ammonia ice. Black smudges, each larger than our Earth, were testimony to the violence taking place in the Jovian atmosphere.

No one questioned that had the comet hit our planet, virtually all life would have perished.

What are the chances?

The bruising of the Jovian world sounded a clarion call for tracking every possible interloper that might one day strike this planet. At a NASA symposium in Washington, astronomer Carl Sagan estimated there was one chance in a thousand that a major comet or asteroid would blast Earth sometime during the 21st century. Sagan emphasized that these were not very good odds. He told the symposium attendees and the press that “you would not go on a commercial airliner if the chance of it falling were one in one thousand.”

Political action for identifying space debris orbits came swiftly, and Jupiter was still sporting bruises when NASA formed the Near-Earth Object Search Committee with the goal of detecting potential killer asteroids and comets. The committee was also told to devise the means for either exploding threatening objects or deflecting their approach to Earth.

Astronomer Eugene Shoemaker — the co-discoverer of Shoemaker-Levy 9 — joined the other experts on the group who warned that at least 15 comets known to swing within Earth’s orbit were big enough to wreak global devastation if they struck this planet. The experts also warned Congress that each day an asteroid the size of a house passes between Earth and the moon, and that we must track these “wolves of the solar system.”

But because our defenses are focused on searching for near-Earth objects and not objects near the solar system’s other planets, another impact was missed in July. Astronomers peering at Jupiter's surface were surprised to see a dark blotch that served as evidence of a recent hit — a hit they never saw coming.

America's place in space

Many longtime space-watchers say that if our leaders in Washington fail to see what’s coming, the United States could quickly fall from its first place in space to the world's fifth-ranked space nation.

Some space hazards can be averted using robotic craft, but others cannot. America needs a robust program for safe rockets and spaceships to serve our needs for generations to come, particularly now that researchers have found water beyond Earth in unexpected places. Precious water molecules have been detected all over the surface of the moon, and sheets of pure ice have been found within fresh craters on Mars. If Americans do not eventually build colonies on our nearest space neighbors, the Chinese and Russians and Japanese and French will.

Taking its direction from the accident investigation board that was formed after the 2003 Columbia tragedy, NASA designed Project Constellation with an overriding concern for crew safety. The agency’s best minds found that two rockets were needed.

The first rocket would be called Ares I. It would be 45 times safer than the space shuttle and would haul astronauts and their all-new Orion spaceship most anywhere. The second would be called Ares V. It would be the most powerful rocket ever built. Without a single human on board, it would haul enormous freight. It would dock with piloted spaceships and supply astronauts with the equipment needed to reach the moon or Mars or asteroids.

After four years of work and $9 billion of funding, the first Ares 1 prototype is ready for a test flight on Tuesday.

The asteroid angle for Ares

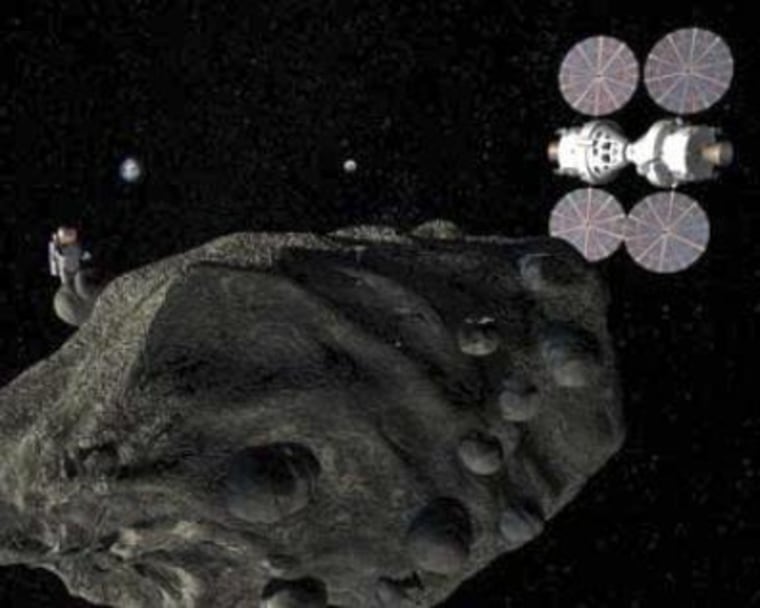

Ares' future course is in Obama's hands, and if the president sticks with Project Constellation, America will build a space transportation system capable of visiting asteroids as well as the moon and Mars.

Slideshow 12 photos

Month in Space: January 2014

"It makes perfect sense for the Orion spaceship to carry astronauts 'rock-hopping' first on a million-mile, six-week trip to asteroids before setting out on the months-long journey to Mars," said Charlie Precourt, former chief of NASA's astronaut corps. Precourt was a three-time shuttle commander and is now a vice president at ATK Space Launch Systems, one of the companies involved in the Constellation effort.

What NASA learns from asteroid expeditions could be crucial for a possible planet-saving mission. And men and women, as well as their machines, will be crucial to the success of those expeditions.

Aerospace engineer Robert Zubrin, president of the nonprofit Mars Society, likes the logic of shakedown missions to asteroids. He told Air & Space writer Michael Klesius that “asteroid flights would help validate the Constellation hardware. Sort of like Columbus getting out there and saying, ‘There aren’t dragons out here after all.’”

Advice from America's first spaceman

The first American in space was Navy Adm. Alan Shepard, a son of New England, cut from the same bolt of Americana as Charles Lindbergh and Neil Armstrong. I had the honor of being his lead writer on the only book he ever penned, "Moon Shot."

While we were writing that best-seller, the subject of killing America’s space program came up. Shepard’s face turned serious. His eyes looked upward — possibly toward the moon, where he had stood on the lunar surface crying as he stared back at Earth, the only place known to harbor life.

"It’s simple," he began slowly. "America needs to keep its best minds working in the halls and labs of NASA — robots as well as astronauts flying throughout the solar system. We need science chugging along under full steam, and astronauts driving the engines where needed.

“Humans left their caves — what was it, about 17,000 years ago, following the second ice age?” he asked soberly. “If we ever turn back, where would we go? Back to the caves? Wouldn’t we be killing the tree of knowledge — cutting away all its branches, its very last leaf?”

Optimism suddenly returned to Alan Shepard’s face, and he flashed his famous Tom Sawyer grin. “Do we really want that?” he asked. “Do we?”

More on near-Earth objects | Ares rocket