Republicans hope to use their new Senate majority to swiftly shape a more conservative judiciary, and they could begin confirming some of President Bush’s bottled-up judicial nominees as early as this month, legislative sources said Friday.

Less than a week before Election Day, Bush repeated the longstanding Republican accusation that the Democratic-led Senate Judiciary Committee was stalling on his nominees for appeals court judgeships. “Our federal courts are in crisis,” he complained, because of “a poisoned and polarized atmosphere in which well-qualified nominees are neither voted up or down.”

While probably little can be done to reverse the political bitterness that swirls around the president’s constitutional power to appoint top judges for life, Republicans expect to get some of Bush’s more controversial nominees on the bench quickly.

Some congressional aides and legal commentators said they would be surprised by significant action during the lame-duck session that begins next week, saying the biggest questions before Congress were the still-to-be-passed 2003 budget and legislation to create a Cabinet-level department of homeland security.

“There’s no stomach for the fight,” said Paul Rosenzweig, senior legal research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative policy institute in Washington. Trying to force through judicial nominees before the next Congress returns would be “like taunting the bull.”

Lame-duck votes?

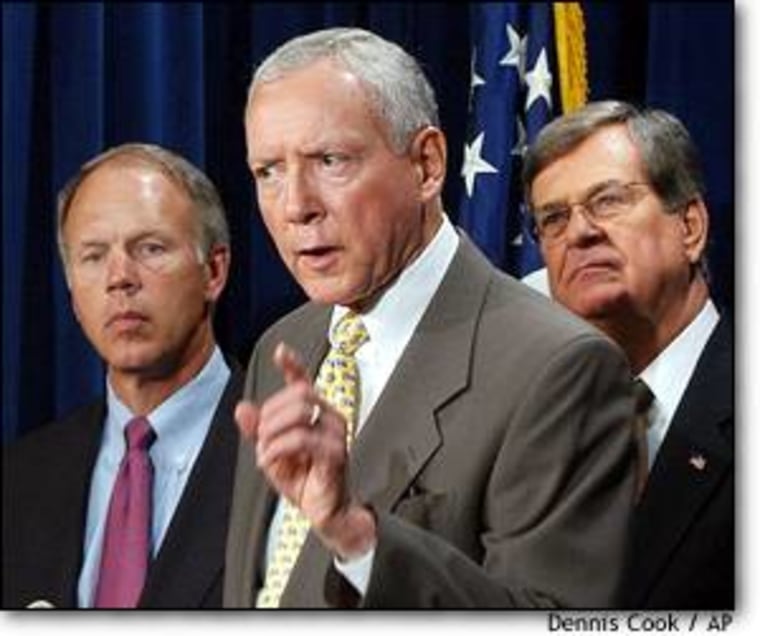

But Margarita Tapia, a spokeswoman for Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, the incoming chairman of the Judiciary Committee, told MSNBC.com on Friday that Hatch did hope to bring three long-stalled appeals court nominations to the floor during the lame-duck session.

The candidates, whom the committee has yet to vote on a full year and a half after they were nominated, are:

Miguel Estrada, a former federal prosecutor who is widely considered a potential future Supreme Court nominee. If confirmed, Estrada would be the first Latino judge on the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, which is considered second in importance only to the Supreme Court. Democrats praised Estrada’s qualifications, but they said he was simply too conservative.

Michael McConnell, a professor at the University of Utah law school who was a Justice Department lawyer during the Reagan administration. He was nominated to the 10th Circuit Court in Denver but has encountered fierce opposition from abortion-rights supporters.

U.S. District Judge Dennis Shedd, a former aide to Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., who was nominated to the 4th Circuit Court in Richmond, Va. Liberal activist groups said Shedd’s limited record — barely 60 published opinions in a dozen years on the bench — raised questions about his qualifications, but many Republicans would like to see him confirmed in tribute to Thurmond.

“We plan to move them as soon as possible. ... In the case of Dennis Shedd, it would be the decent thing to do before Senator Thurmond’s historic Senate career comes to a close,” Tapia said.

Round 2 for Pickering, Owen

David Carle, a spokesman for the Judiciary Committee’s outgoing chairman, Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., disputed Republican claims that the committee had sat on an excessive number of Bush’s nominees, saying the committee had approved 98 of the 100 nominations it voted on in the Democrats’ 15 months in control. The Senate subsequently confirmed 80 of them, and the remaining 18 await floor votes.

But Republicans said there were many others that were never allowed to come to a vote in the committee. And they have turned the two that were rejected into rallying points.

Once the new Congress returns in January, with Republican Trent Lott of Mississippi as the Senate’s majority leader, Republicans expect Bush to resubmit the names of those two highly controversial nominees, both of whom were put forth for prestigious appeals court positions: U.S. District Judge Charles Pickering of Mississippi and Texas Supreme Court Justice Priscilla Owen.

“I hope the Judiciary Committee will let their names out and they get a fair hearing,” Bush said last week.

Rosenzweig predicted that Pickering and Owen would be among the first items on the Senate’s agenda and said they could be confirmed as early as late January, unless “the Democrats chose one of those to be the first one they filibuster.”

Carle would not comment on Republican plans to revive the failed nominations, but the plan appeared likely to energize opponents.

“For the president to renominate either of them would be the ultimate politicization of the process,” said Marcia Kuntz, director of the Judicial Selection Project of the Alliance for Justice, a coalition of liberal activist groups based in Washington.

“It would reflect a lack of respect for the institution and for the legitimate constitutional process that the institution went through in rejecting the nominations of Pickering and Owen,” she said.

Few weapons for Democrats

Liberal interest groups promised to fight what Kuntz called “any packing of the courts with conservative ideologues who are beholden to special interests and committed to turning back the clock on Americans’ rights.”

Leahy called on Bush to choose “more noncontroversial nominees” but said in a statement that he expected more “disagreements over nominees who are chosen primarily for their ideology and not for their independence.”

Democrats have only a limited range of options.

They can filibuster individual nominations on the Senate floor, but senators have traditionally been reluctant to do so in modern times. Legislative aides and legal observers said filibusters of judicial nominations were a crude weapon that could create a voter backlash because they were direct and highly visible repudiations of a president’s prerogative.

Democrats will also find filibusters tough to sustain in the new Senate. With one independent and several conservative Democrats in the new session, Lott should be able to round up the 60 votes he would need to quash such maneuvers, congressional staffers predicted.

Short of the filibuster, “there are delay tactics available, obviously, but in terms of stopping them, it’s hard,” Rosenzweig said. “If they can’t use the filibuster, it’s hard. Then you’ve got to convince 51 to vote no.”

Democrats could also adopt “the tactic of defeating nominees by demonizing them,” he said. “That, too, is a blunt tool, but it’s available. They used it against Robert Bork.”

Kuntz of the Alliance for Justice acknowledged the difficulties for Democrats and their allies.

“The president has made it clear that this is a high-priority issue for him, so we expect that he will nominate people pretty quickly and that there will be a push in the Senate to move people quickly,” she said. “And we’re just going to continue to urge the Senate to take its constitutional role seriously and to thoroughly scrutinize every nominee.”